The last time I was in London was in 1997 on a family trip. I vaguely remember passing by Buckingham Palace and being enchanted by the possibility of an actual queen inside it.

I have encountered the British royal family several times since then—on a plaque in my school placed in the honour of some queen, prince, or princess that I cannot remember, on a vintage coin my grandmother had saved, and when my parents added a cassette of Princess Diana’s funeral to our collection.

I was an impressionable young girl back then, with no knowledge of the ghastly impact of the British Empire on India’s people except that they stole a really large diamond called the Koh-i-Noor.

As a child growing up in India’s post-liberalisation 1990s, this was a particularly ahistorical time in middle-class Indians’ lives. Our goals were typically bourgeoisie, focussed on amassing wealth in a suddenly consumption-driven economy.

My point is, at the time, I could listen to the Princess Di memorial cassette with no sense of irony. This, despite belonging to a family that suffered great emotional, financial, and human loss during India’s partition in 1947. Back then, I could separate the brutal British Empire in India from the jolly and fashionable royalty on television.

Thanks to literature and a deeper understanding of history, that imaginary screen door between the two Britains was shattered. While reading the short stories of Saadat Hasan Manto, my blood boiled. In Khushwant Singh’s A Train To Pakistan, I heard my grandmother’s grief. In Anita Anand’s The Patient Assassin, I saw the generations that the empire destroyed for its own capitalist and military gains.

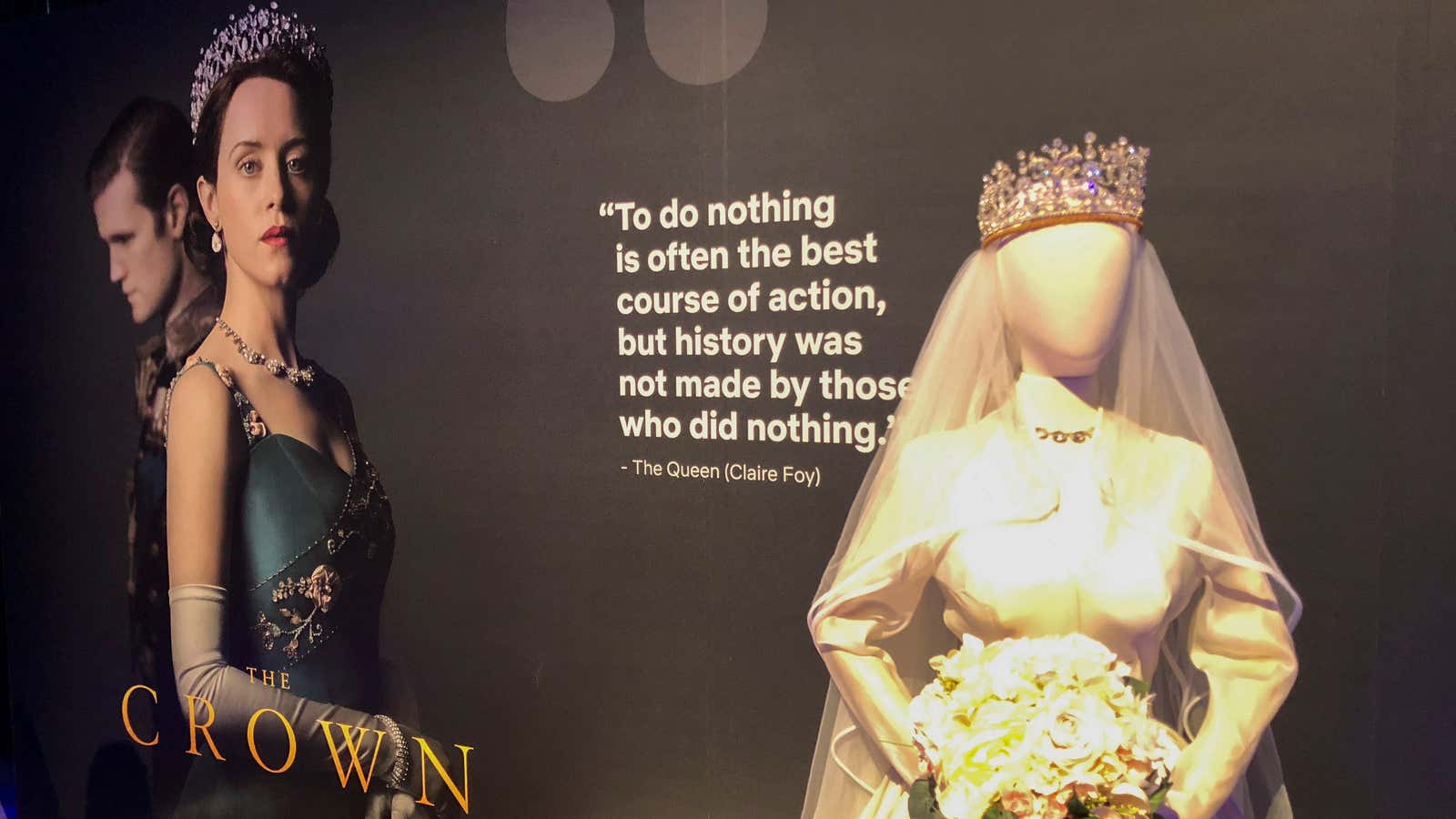

Cut to 2016, when Netflix premiered The Crown, that sense of irony and historicity vanished in the grandeur of the series’ production value.

Netflix’s The Crown

I binge-watched all 10 episodes of the first season, and then re-watched them for Claire Foy’s sparkling reticence. Begged and borrowed friends’ Netflix passwords for the subsequent two seasons. And put a reminder on my phone for the latest season of the series that captures the life and struggles of Olivia Colman as Queen Elizabeth, and her seemingly complex large family.

The Crown can give Indian soap operas a run for their money, and in that there is pure entertainment value. The predictably manipulative soundtrack only aids its ability to be devoured. The superlative acting from Foy, Colman, and Helena Bonham Carter lit up the television screen. And my father, a recent recruit to this “historical” drama, was delighted to report that he would be watching the rest of the series to learn new vocabulary. (I have added “zhuzh” to my lexicon thanks to Diana.)

But as I rewatched some of the old episodes—besides the wildly upsetting ones with Charles and Diana—all that history I could thus far ignore washed over me.

No amount of rousing music could block out Netflix’s whitewash over Britain and the royal family’s gruesome colonialism and racism. The glorification of Winston Churchill, the man who was responsible for the death of millions in India during the Bengal famine of 1943, rankled more than it did four years ago.

On social media, I found kindred spirits who seemed to be feeling a similar resurgence of anger towards the injustice that the Netflix show conveniently sidestepped. These voices appeared louder this time around, either because Netflix now has more subscribers in India than it did when The Crown first aired. Or, that I was afflicted with a confirmation bias.

Parliamentarian Shashi Tharoor, who has been a vocal proponent of the idea that Britain has immense reparations to make to its former colonies, also had a timely meme handy.

I watched bits of The Crown again, especially to see the valorisation of Lord Mountbatten and the absolute silence over the violent legacy he has left behind in the Indian subcontinent.

And to remind myself that Hindi television soap operas, ridiculous as they may be, were delightful in the fictional escapism they provided. Watching The Crown, even if ambiently, offers an escape from history, and that’s never good news.