Amitabh Bachchan’s 753rd tweet—the superstar carefully numbers his social media activity—was a somewhat unfunny joke on rising inflation. Fed up with rising petrol prices, a Mumbaikar goes to a petrol pump to buy “two to four rupees” of petrol in order to “spray on his car” in order to “burn it.” Clearly, it was unviable for a middle-class Indian to now even own a car.

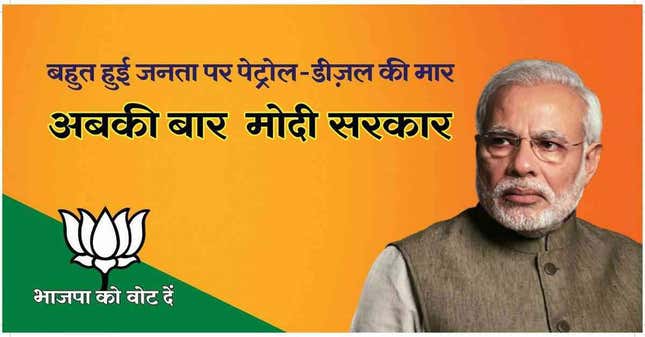

This was in 2012—a time when jokes around the price of petrol were so popular they almost made up their own humour genre in India. This was also a time when the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance was tottering. And as it soon learnt, there was little more damaging politically than humour. The widespread mocking of fuel prices served to create a middle-class “common sense” that the UPA was a time of exceptional misrule and corruption.

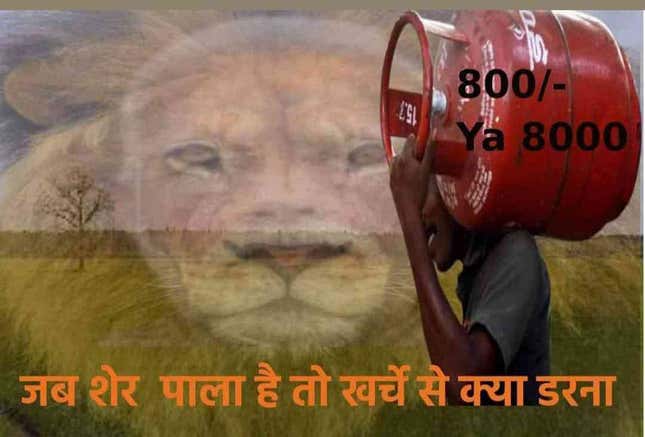

Since then, oil prices have skyrocketed, going up approximately by a quarter. This week they even crossed the psychological barrier of Rs100 ($1.38) per litre in some cities.

Radio silence

Ironically, unlike the torrent of petrol price jokes in 2012 and 2013, there was little this time even though the prices were not only much higher, they were far more due to the government’s actions. While taxes and duties comprised only 49% of retail petrol price under the UPA, under Modi that figure stands at 67%, as per an analysis by Mint.

This isn’t the only instance of the middle-class getting squeezed with little political repercussions. For some time now, the Reserve Bank of India has kept interest rates low, in a bid to kickstart the sputtering Indian economy. While this policy helps large corporations access easy credit, it grievously impacts small savers. For example, the rate for a State Bank of India fixed deposit between five and 10 years stands today at only 5.4%. This is down from more than 9% when Bachchan was joking about the travails of the middle-class in 2012.

Since fixed deposits are a key way for the middle-class to earn interest income, this hurts them significantly. Moreover, it disportionately hurts the vulnerable elderly section, who have depended on these instruments for retirement income only to see their corpus shrink dramatically as a result of this new interest rate regime.

This is not all. Even as expenses shot up and saving avenues close, middle-class incomes have been badly hit by policies such as India’s harsh Covid-19 lockdown. Survey work by the economic research firm Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy has found that middle-class and upper middle-class Indians were the worst hit by the lockdown in terms of income growth.

Blame game

Given how significant the petrol price rise is, Modi has directly taken on his critics using the much used—and till now fairly efficacious—device of blaming previous governments. “Had we focussed on this [energy import dependence] earlier, our middle-class would not be so burdened,” the prime minister said on Wednesday.

There is little fact behind this statement, given that—as pointed out earlier—much of the retail price paid for petrol is due to the Modi government’s own excessive taxation. However, in spite of this price increase and attempts to palm off blame, there is hardly any middle-class anger even resembling that which existed during the last years of the UPA.

Vote bank

This silence in the face of economic hurt underlines the strong support for the BJP, Modi, and eventually Hindutva from India’s middle-classes. Most data points to the fact that in the middle-class, the BJP has a more stable vote bank than almost any other party in India. In 2019, one of the largest post-poll surveys done across India found 38% among middle-class respondents and 44% among the upper middle-class voted BJP which was, by far, the most popular party in that category. Since the BJP appeals only to Hindus amongst the middle-class, an astounding 61% of Hindu upper-caste voters surveyed picked the BJP in 2019.

This points to a deep ideological relationship, which clearly has the potential to withstand economic shocks, with the Indian middle-class, at least for the time being, ready to vote against their own economic interests.

What works additionally in favour of the BJP is the lack of any other party which attracts middle-class support. Congress, while traditionally a party that attracted middle-class support, has seen its support collapse post 2014, with the BJP significantly increasing its standing amongst them between 2014 and 2019.

What is often disparagingly called “vote bank politics” in India—pointing to the existence of identity-based support—has helped the BJP significantly even as poor economic conditions force it to squeeze its own middle-class base.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.