After much debate and delay, India has decided to open up its Covid-19 vaccination drive to all adults over the age of 18 from May 1. But if the past track record of vaccine administration in the country is anything to go by, this policy change might not make much of a difference to the lives of ordinary Indians.

In December 2020, India had estimated that it would vaccinate 300 million people by August. This target included healthcare and frontline workers, and Indians over the age of 50 who have co-morbidities. On April 1, the government relaxed the eligibility for the vaccine further to include all those over the age of 45.

Yet, in the 94 days since the vaccination drive began, the country has fully vaccinated only 17.4 million people, with nearly 100 million Indians receiving at least one dose. At the moment, India has been administering a little over 3 million doses on average per day.

But, for the country to even meet its initial target of 300 million people by August, it would need to administer an average of 4.7 million vaccines a day. And as it opens up the drive to an additional population of roughly 600 million, it would need to push the pedal even to get the priority groups vaccinated first.

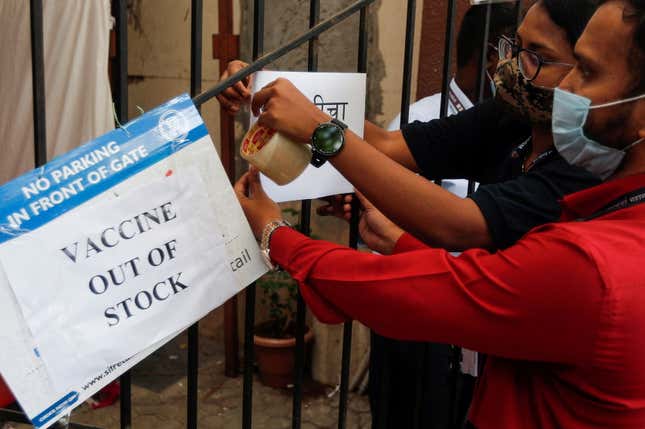

It doesn’t help that the decision to allow all adults to get vaccinated comes in the midst of a worse-than-ever Covid-19 surge, with the country reporting over 250,000 new infections every day. It also comes at a time when India is grappling with a vaccine shortage domestically, while its vaccine makers scramble to fulfil international orders.

Vaccine shortage and delivery

Vaccine makers in India have not been able to ensure production at a pace that can keep up with both the domestic and international demand. Both Bharat Biotech and Serum Institute of India, whose vaccines are currently authorised for emergency use in India, have asked the government for funds to ramp up their facilities to this end.

A source-based report says the Indian government has cleared Rs3,000 crore ($400 million) for Serum Institute of India, and Rs1,500 crore for Bharat Biotech as “an advance” for them to meet their orders on time.

Several states in India have had to slow down their vaccine rollout, and even temporarily shut their vaccine centres because of a dire shortage of jabs. In the face of such shortage and the demands to widen the scope of the drive, health secretary Rajesh Bhushan had said on April 7 that the jabs are meant for “those who need it” and not merely those who “want” it.

India, unlike the US and other parts of the developed world, has low vaccine hesitancy. But awareness about the drive in India’s villages and remote districts would be needed to meet the vaccination target.

A part of this shortage could be met once the Covid-19 vaccines are available in the private market. The government has proposed that 50% of the vaccine stock be directly sold by manufacturers to the states, and allow private establishments to sell the vaccine at cost.

What this price will be is yet to be determined, which could have its own problems of inequality and uneven supply.

India is among the only countries in the world where citizens currently pay for the vaccine at private vaccination centres. While it is still free at government-run healthcare centres, this might soon change as more citizens in a country of 1.3 billion become eligible.