On the night of April 19, Mankeerat Kaur and her entire family tested positive for Covid-19. While her husband and son had mild symptoms, Kaur, 51, who worked as a volunteer at non-profit organisations in Delhi, began to experience breathlessness.

“We had three oximeters just to be sure of the readings,” said her husband Kavaljit Singh, 57. “They showed her levels at 84.”

With a brutal second wave of Covid-19 overwhelming hospitals in the city, families were struggling to find beds for sinking patients. Singh, however, managed to get his wife admitted to the Delhi Heart and Lung Institute on April 23, as her oxygen saturation dipped to 80.

Nearly a month later, Kaur passed away on May 19, her body wracked by multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

After her death, the facility issued a 22-page bill of Rs19 lakh ($25,938) that Singh has been unable to pay.

Of the total bill, Rs2.2 lakh are charges for critical care—Rs15,000 per day for four days spent in the ICU for four days and Rs18,000 for nine days using a ventilator unit. About Rs1.1 lakh are charges for staying in a single room and coronary care units at Rs8,500 and Rs9,000 per day for the remaining two weeks.

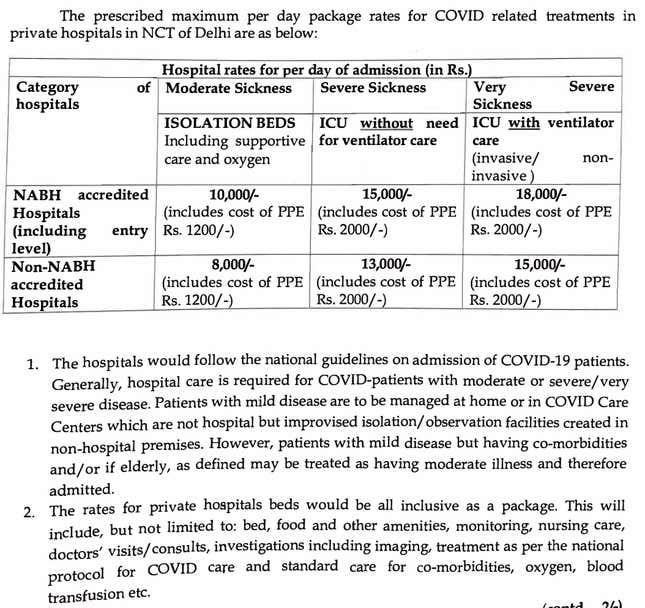

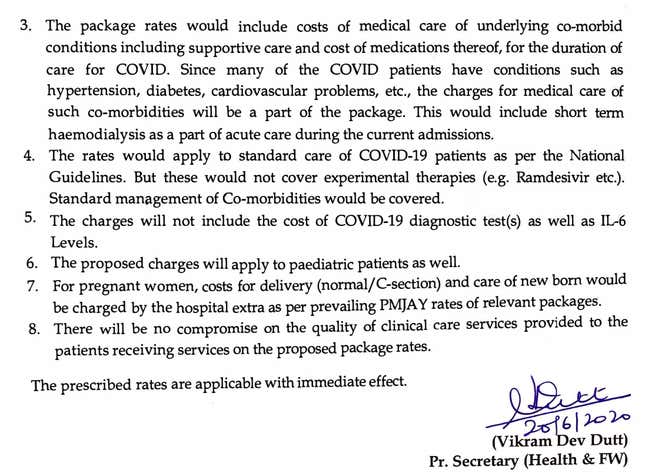

In June last year, the Delhi government had fixed prices for the treatment of Covid-19 patients at 60% of the beds reserved at private hospitals. It capped prices at Rs10,000 for an isolation bed, Rs15,000 for an ICU bed and Rs18,000 for an ICU unit with a ventilator.

The order states that these capped prices would include “bed, food, other amenities, monitoring, nursing care, doctors’ visits, consults, investigations…and standard care for comorbidities, oxygen, blood transfusion.”

But Singh was separately charged Rs11.8 lakh under the category of pharmacy which includes medicines, masks, bandages, sterile swabs, and N95 masks; Rs1 lakh for consultations; Rs96,170 as laboratory charges for tests; Rs27,350 as nebulisation and intubation charges; Rs16,500 for oxygen; and Rs15,000 as plasma therapy among other miscellaneous expenses.

Singh, grieving for his wife, did not challenge the hospital when he was presented with the bill, and even now, after he has had time to gather his thoughts, has no intention to contest the charges.

But speaking to Scroll.in, he pointed out that, let alone furnishing clear information on what the capped prices included, the hospital had not even displayed basic information about the price caps. Neither did the hospital clarify how many beds had been reserved under the Delhi government order, and whether his wife had been given one of those beds. Scroll.in sent queries regarding this to the hospital. This article will be updated if they respond.

Public health activists say Singh’s experience speaks of a larger problem: Delhi government introduced price caps on Covid-19 care at private hospitals, but failed to enforce them. This put the city’s residents, already struggling with trauma, anguish, and loss in the second wave, under tremendous financial strain. For some, it has wiped out their savings.

Tending to illness and bills

Between April and May, Delhi saw an average of 20,000 recorded cases per day. In the absence of a centralised bed allotment system, the families of patients were forced to run around to look for beds. A shortage of beds in government facilities pushed several to private hospitals, even if they could not afford the cost.

“Private hospitals in Delhi had a completely free hand in terms of what they wanted to do and how they wanted to charge,” said Inayat Singh Kakar, a public health activist and a volunteer at the Covid Citizen Action Group.

The June 2020 order clearly states that the per day charges include treatment, medicine, and other miscellaneous costs, except the charges for a Covid-19 test, an IL-6 test that checks inflammatory response and experimental treatments such as Remdesivir. But, because of the lack of enforcement, said Kakar, private hospitals “tell patients that the package rate is separate from other expenses”.

What allows them to get away with this, she added, is that the government’s Delhi Fights Corona dashboard does not show how many beds are reserved in each hospital under the price cap order.

A petition filed in Delhi High Court on May 31 by the All India Drug Action Network has sought to address these ambiguities and loopholes, as well as the lack of grievance redressal mechanisms for patients.

The network suggested the government issue a separate order clarifying “the costs that are included within the package rates and also to explicitly prohibit hospitals from billing patients for these treatment costs over and above the package rates”.

The court has asked the Delhi government to file a status report on the complaints of patients by June 23.

Queries to the Delhi government regarding the enforcement of the order went unanswered. This article will be updated if they respond.

Pending hospital bills

For families with a single breadwinner, the financial distress has been devastating.

Shivang Gupta, 28, a civil engineer in the construction department of Amity University, has had to support Covid-19 treatment for his entire family out of his monthly income of Rs8,000.

A resident of Ghaziabad, abutting Delhi, he tested positive for Covid-19 on April 20 along with his parents and brother. A week later, his brother was the first to be admitted to a hospital in Ghaziabad with high fever, followed by Shivang Gupta himself. Their parents, experiencing breathlessness, were also hospitalised by May 2.

While the brothers recovered and were discharged from the hospital on May 3, their father died on May 5. Their mother spent another three days in hospital. By now, the family had notched up hospital bills of Rs3.7 lakh, with his mother’s treatment alone costing them Rs1 lakh. None of the family members had insurance, except for Gupta, who was insured by his company.

His mother, a diabetic, was discharged from the hospital on May 8, but when she returned home her stomach hurt uncontrollably. The family admitted her to Sarvodaya Specialty Hospital in Ghaziabad, where doctors initially said she had developed urine and blood infection, but later revised the diagnosis to mucormycosis, a deadly disease commonly known as black fungus. The hospital asked the family to take her to a facility that could treat the disease, furnishing a bill of Rs1.75 lakh for 10 days.

Max Patparganj in East Delhi, where Gupta’s mother was admitted next, gave an estimate of Rs2.5 lakh for surgery to treat mucormycosis. But after an MRI scan, the doctors said she was not infected with the fungus, rather she had a “blood clot in her stomach of 1.5 litres,” Gupta said.

After a surgery to remove the clot on May 21, she stayed on a ventilator for four days, before she was shifted out of the ICU—only to be brought on May 28 because of a dip in oxygen saturation level. “They said her heart was not entirely functional and the muscles around it were weak,” Gupta said. On June 2, she was taken off the ventilator again, but is still recuperating in the hospital.

In the midst of the emotional roller-coaster, Shivang Gupta has had to contend with a bill of Rs17 lakh—Rs4.7 lakh for drugs, Rs3.9 lakh for investigations, Rs2.2 lakh as room rent, and Rs1.3 lakh as consultations among other charges.

For the family, this is way beyond their means. Gupta’s father and elder brother run a small photography business, which has been in a state of collapse since the pandemic began, he said.

To pay off the bills, Gupta created a fundraiser online from which he was able to raise Rs2.5 lakh. He borrowed from friends and relatives after exhausting most of what he earned. “All my savings have gone in this,” he said.

So far, he has been able to pay Rs12 lakh. He still has to raise the remaining Rs5 lakh.

“Have to pay from our pockets”

Kavaljit Singh is more affluent than the Gupta family. A director of Madhyam, a policy think-tank, he earns nearly Rs2 lakh per month, he said. Still, the high cost of his wife’s treatment has come as a shock.

“We are all emotionally raw and struggling to get through the trauma,” he said. “There is anger and our lives have been upended by her passing away. Everything collapsed.”

Of the Rs19-lakh bill, Singh has been able to pay about Rs10 lakh so far, a portion through a medical insurance cover of Rs4.8 lakh.

In the past, there was no reason to believe their medical insurance may fall drastically short. “We did not think of getting insured for Rs20 lakh, we just bought it according to the rates for other treatments,” he said.

He said he would make the pending payments from his own pockets. “There is no time for crowdfunding,” he said. “A lot of relatives would like to help but I do not want to take a penny from anyone.”

Despite the financial setbacks that middle-class families of Covid-19 patients have experienced because of the exorbitant bills charged by private hospitals, activists say they are unlikely to change their healthcare preferences. “I don’t think that people are going to suddenly love public hospitals,” said Kakar. “Privatisation is here to stay.”

Families might, in fact, invest more in buying larger medical insurance packages to secure themselves. “More people will prefer to get insurance for private hospitals so they do not have to go to a public hospital,” she said. “They will do it out of necessity.”

This article first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].