When Portugal was recently removed from England’s green list for travel, the UK transport secretary, Grant Shapps, blamed it on a new coronavirus variant. “There’s a sort of Nepal mutation of the Indian variant which has been detected,” he said in a recent interview.

This was the first time most people had heard of a “Nepal mutation”. Indeed, the World Health Organization said that it is “not aware of any new variant of SARS-CoV-2 being detected in Nepal.”

And, according to Public Health England (PHE), there is no “Nepal variant of interest” or “variant of concern.” So what is this variant Shapps is speaking of? Does it even exist?

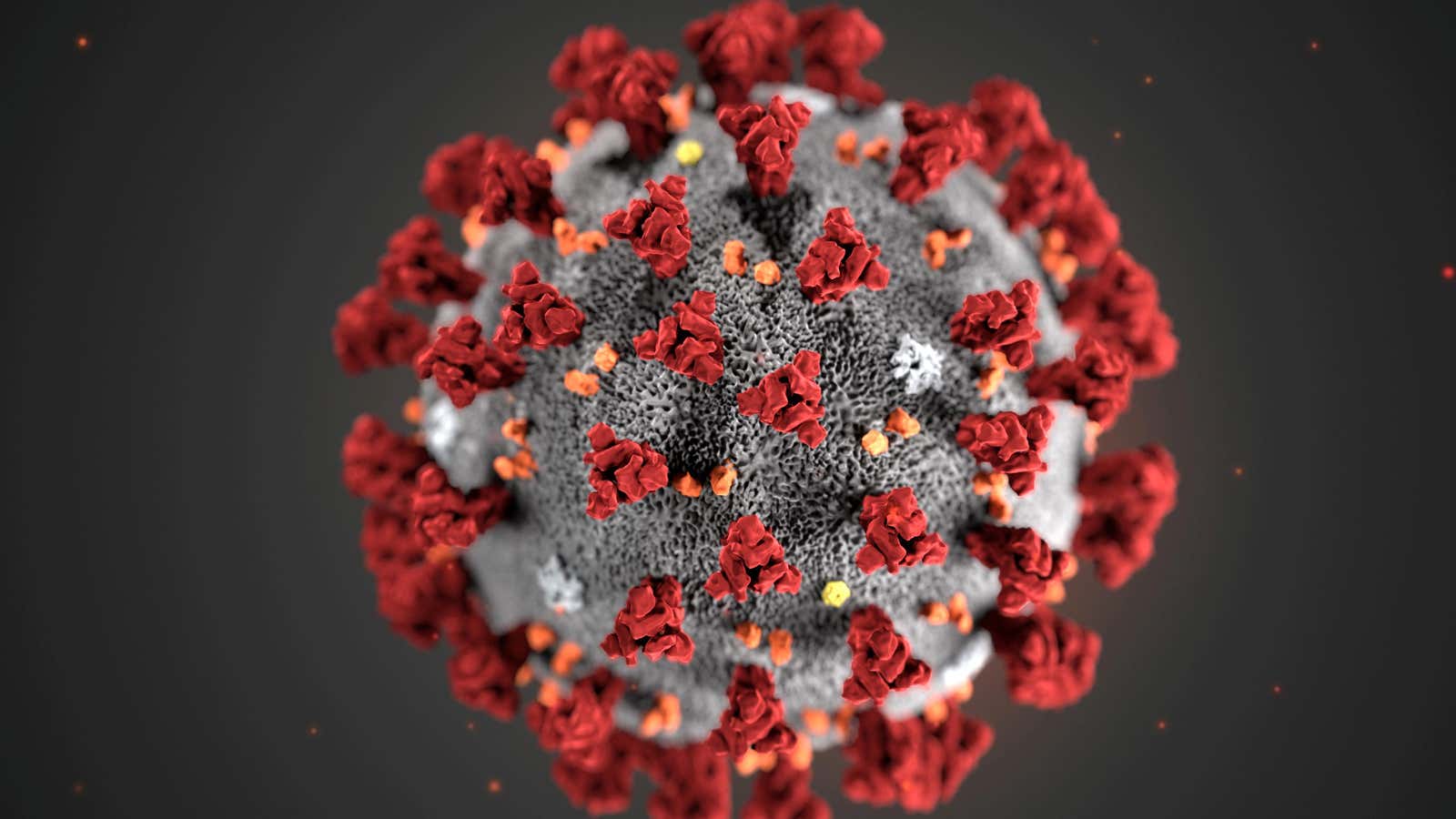

The “Nepal variant” turns out to be the Delta variant—the one first detected in India and currently making up over 90% of cases in the UK—plus a mutation known as K417N. The K417N mutation is in the spike protein (the mushroom-shaped projection on the surface of the coronavirus that helps it to enter human cells).

The first five cases in England were sequenced on April 26, according to a recent PHE report, and were contacts of travellers to Nepal and Turkey.

At the latest count, there are 36 cases of the “Nepal variant” in England. Most of the cases are in younger people, with two cases in people 60 or over. Out of the 36 cases, 11 were “travel-associated” (six travellers and five cases among contacts of travellers).

The vaccination status of 27 of the 36 recorded “Nepal variant” cases were known, and the records showed that 18 cases were in people who weren’t vaccinated. Only two cases were in people who had received both vaccine doses and had more than two weeks between the second dose before being tested positive. No deaths from this variant have been recorded.

Why the concern?

Despite the low number of cases of the “Nepal variant,” what has got people concerned is that it is the combination of the highly successful Delta variant (which has killed hundreds of thousands of people in India) plus the K417N mutation, which is found in the beta variant—the variant first detected in South Africa, and gamma, the variant first detected in Brazil.

Although the beta variant doesn’t appear to be anywhere near as transmissible as the Delta variant (look how quickly it took over from the alpha variant in the UK), it is beta’s K417N mutation that is believed to help the virus dodge neutralising antibodies—a vital part of our immune system’s defences. This means it can make vaccines and antibody drugs less effective, and increase the risk of reinfection, as happened on a large scale in Manaus, Brazil, with the gamma variant.

So you can see why PHE is keeping a close eye on the situation. However, without epidemiological and laboratory evidence that the “Nepal variant” is more transmissible, virulent or better able to evade vaccines than the Delta variant, say, the “Nepal variant” will remain off the worry list—at least for now.

How this will play out in the next few weeks and months, though, is anyone’s guess. But one thing is sure: if Delta Plus K417N does join the World Health Organization or PHE’s list of variants of concern, it will not be called the “Nepal variant”. It will be designated a Greek letter. Variant names that stigmatise countries are being phased out, but perhaps Shapps didn’t get the memo.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.