A vaccine developed in Africa has far-reaching consequences for malaria eradication in India, where the disease has claimed millions of lives and cost people their livelihoods over decades.

Mosquirix, the world’s first malaria vaccine developed by GlaxoSmithKline, was approved yesterday (Oct. 6) by the World Health Organization (WHO). While children in African countries, where the burden of the vector-borne disease is the greatest, will benefit the most from the development, it will go a long way in reducing the number of cases and fatalities in countries like India, too.

India has, over the years, made strides towards reducing its malaria burden, with the number going down from 20 million cases in 2000 to 5.6 million in 2019, according to WHO’s World Malaria Report 2020. This was the biggest absolute drop in Southeast Asia, the WHO had noted.

The country, however, still accounted for around 86% of all malaria deaths in the region—in 2019, up to 7,700 people died of the disease compared to 29,500 in 2000.

The Indian government is now eyeing complete eradication of the endemic disease by 2030.

Malaria’s impact on India

While India’s share in the overall malaria caseload is only 3%, its economic ramifications are huge. In total, it cost the country around $1.9 billion (1.42 lakh crore rupees), according to estimates from 2014 published in the WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health by Indrani Gupta and Samik Chowdhury.

India had nearly eliminated malaria fatalities in the 1950 and was working towards eradication in the 1960s. A key element of this strategy was spraying the insecticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) in indoor spaces.

However, a subsequent shortage of DDT, some policy-level complacency, and insecticide resistance developed by mosquitos led to a resurgence of the sickness in the 1970s, Dr VP Sharma wrote in the Indian Journal of Medical Research.

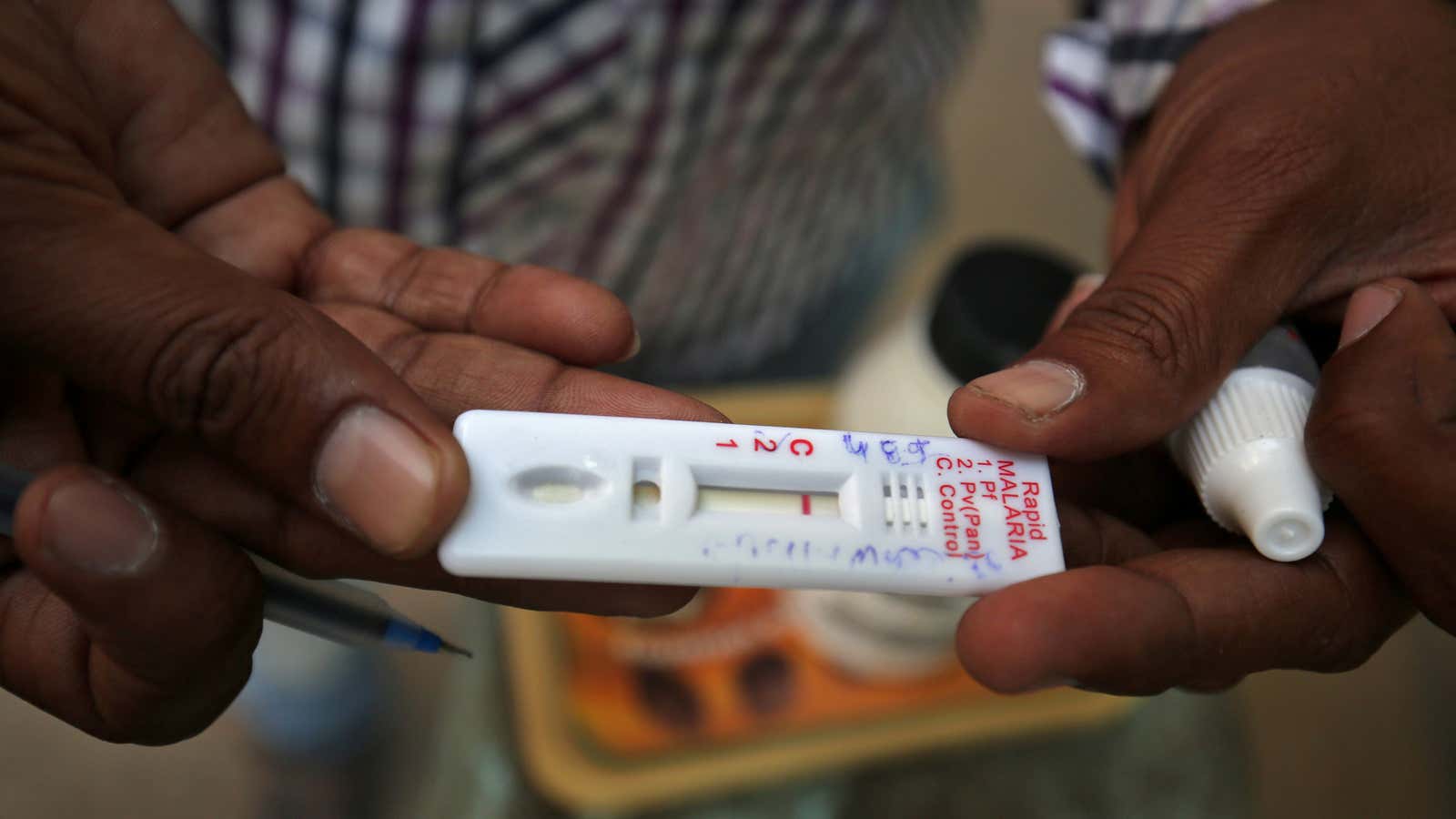

Over the years, the country has recalibrated its approach, introducing measures such as insecticide-treated nets, mobilising community health workers to spread awareness, and reducing the mass use of choloroquine to prevent drug resistance.

In 2017, the government announced its National Strategic Plan for malaria elimination till 2022, eyeing complete eradication by 2030. With Mosquirix, it can now focus on susceptible states like West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh.

History of malaria—and gin and tonic—in India

A fundamental understanding of the parasite, the female anopheles mosquito, that spreads malaria and the impact the disease has on the human body came mostly from research done by Dr Ronald Ross.

Born to British parents in the Himalayan town of Almora in India, Dr Ross went on to become only the second person in history to win the Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1902 for his work on malaria.

The disease had greatly affected British officers posted in tropical parts of the country in the 19th century. At the time, quinine was deemed a cure but was too bitter. Tonic water—quinine in a carbonated base—made it more palatable.

But what truly got British troops to consume the antimalarial without much resistance, perhaps, even to enjoy it, was converting it into a cocktail: gin, a touch of sugar, and a wedge of lime.