India’s top medical research body may be making tall claims about Covaxin’s efficacy against omicron—but most of it may be based on little or no data.

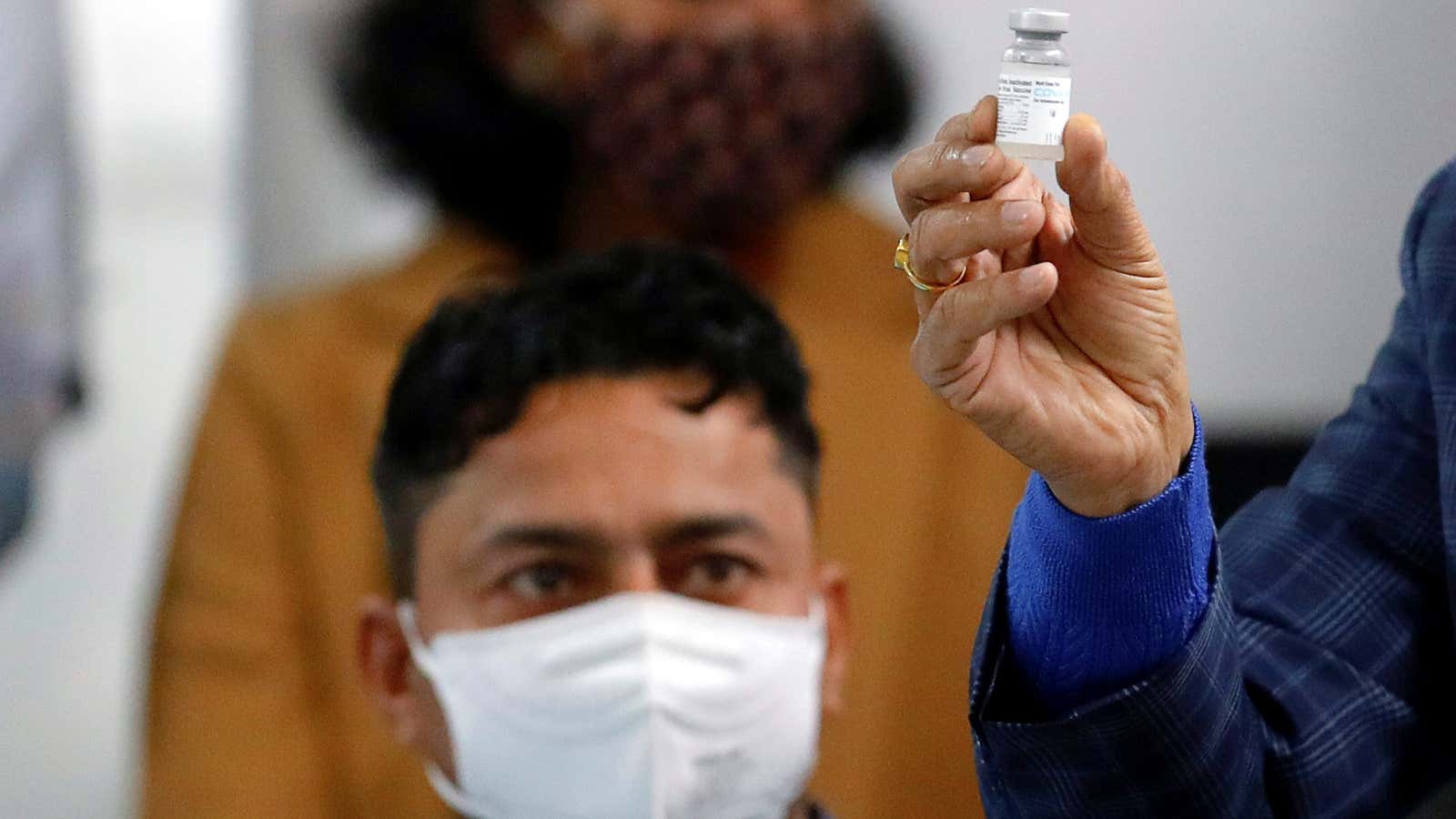

The government’s Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR), which co-developed Covaxin with Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech, has claimed that its covid-19 vaccine may have an edge against other shots currently available when it comes to new variants.

Though he added a caveat that very little is known yet, “it is a plausible conjecture to say that the virus may have less chance of escaping the immunity given by Covaxin than for other more targeted vaccines where the focus is principally on the spike protein,” Samiran Panda, head of epidemiology and infectious diseases at ICMR, told ThePrint.

The function of the spike protein in novel coronavirus is to infect the host cell, and the new omicron variant has 32 of its mutations in this part alone.

Panda’s contention was that vaccines that target spike proteins—such as Pfizer and Moderna’s mRNA ones—and weaken the virus’s ability to infect its host, offer only one kind of protection. “In the case of Covaxin it is a little like a Bruce Lee assault when three different and potentially fatal sites are targeted at the same time,” he said.

This is a continuation of the belief around Covaxin that because it is a whole virion vaccine—a type that uses the inactivated virus—it is inherently better at fighting off infection.

This belief, put forth by Bharat Biotech’s founder Krishna Ella as far back as January, stems from the fact that Covaxin uses established vaccine technology, unlike the more experimental mRNA platforms. This understanding also makes its way in ICMR chief Balram Bhargava’s book on the development of Covaxin.

And yet, this claim has so far lacked the backing of publicly available data.

Is the Covaxin vaccine inherently better against mutations?

Experts suggest there are many pros and cons of a whole virion killed vaccine, especially when it comes to storage and transportation. These typically do not need ultra-cold storage facilities like the Pfizer and Moderna shots. This is particularly beneficial for low-income countries, which could receive Covaxin shots now that it has been listed for emergency use by the World Health Organization.

“But to date, there is no reliable evidence that they necessarily offer wide-ranging protection against new variants that result from multiple points of genetic mutation,” said Jammi N Rao, an independent public health physician. “The link between genetic mutations and antigenic properties of the virus particle is not sufficiently well understood.”

For this, he said, the vaccine needs to be studied both in the lab (for instance, does plasma from people immunised with Covaxin contain antibodies that neutralise the spike protein in omicron?) and in clinical settings (does Covaxin offer real-life protection against Omicron infection?).

Especially with omicron, about which not enough is known, the claims must be considered with some circumspection.

Vaccine nationalism

In the absence of solid data, Covaxin’s efficacy against omicron is still only a calculated guess. Even against some known variants of concern, the vaccine had reduced efficacy.

For instance, in clinical settings, Covaxin produced fewer antibodies against the delta variant, though it had remained as effective against the alpha variant. This was confirmed by real-world data during the peak of infections in Delhi when Covaxin’s efficacy against covid-19 was reduced to 50% as against its overall efficacy of about 78%.

With a variant with more mutations than delta—and several unknowns—the “Bruce Lee assault” claim may not hold up.

“I can only speculate that it comes not from hard science but from a desire to project Covaxin as better than any other vaccine because it is an indigenously developed vaccine,” Rao said. “It is therefore understandable why many people would want this theory to be true, but it is not the way of science to promote a theory because it is convenient.”

The ICMR could, ideally, take a more straightforward approach: be transparent with data and make statements only when there is a science to back them up.

“When there is insufficient information the best answer is to say, ‘We don’t know,” Rao said. “The true expert is most knowledgeable about the boundaries of his expertise.”