Nidhi Chander* was full of hope until five years ago. That was when she gave up her job as a beautician at a unisex salon in Pitampura, Delhi, where she was earning 20,000 rupees ($270) a month, to work with Urban Clap. She believed the home services start-up would give her the freedoms she had been missing all along: flexible work hours, precious time to look after her children, and independence.

At first, things were great. Although she had to travel a fair distance every day, she could work when she wanted to. Her monthly earnings were almost Rs55,000. She learned she could earn more than her husband, who had lost his job and was driving her around. She bought an air-conditioner, a refrigerator, and even took a loan for an apartment in Ghaziabad.

But then, the rosy picture began to fade. As the company, rechristened Urban Company, expanded globally, inching closer to unicorn status, cascading pressures began to mount on her. There were commission rates to deal with, penalties for cancellations and ratings pressures. Chander’s average net income dropped to Rs20,000 a month. The family rented out their house and moved to cheaper accommodation. Unable to afford the fees, the children were pulled out of school. Her daughter contracted typhoid, and the family had to scramble for treatment.

In October, she says, she considered killing herself. “I had hit a low,” she said. “The monthly instalments were torturing me. The pressure made me sick.”

Other beauticians with Urban Company rushed to help—a moment which Chander believes crystallised their anger into what was possibly India’s first women-led gig workers’ strike. In October, roughly 100 women agitated outside the start-up’s office in Gurgaon to protest “low wages, high commissions, and poor safety conditions”.

That demonstration must have shaken the company, for around a week later, it published a blog post on Medium, announcing a slew of policy changes. Partner commissions were lowered, penalties reduced, and an SOS helpline for women was set up. “In the last couple of days, there have been concerns raised by a few of our partners, and other well-intentioned voices, regarding the earnings and well-being of our service partners,” the company said in another blog post. “We hear you.”

There was an unmistakable note of conciliation in the company’s response. But it was replaced by a confrontational stand when a smaller group of beauticians protested again outside its Gurgaon office in December. This time, the company filed a lawsuit against the protesting “partners”—the term it uses for workers—claiming their actions were “illegal and unlawful.” It sought a court injunction restraining the women from holding any “demonstration, dharna, rally, gherao, peace march, shouting slogans, entering or assembling on or near the office premises.”

Chander was at the October protest. Sitting on a twin bed in her one-bedroom flat in Paschim Vihar, Delhi, in December, the 29-year-old bemoaned her lot. Her two daughters rolled up the mattresses on the floor, marking the start of a new day. Her husband counted the samosas to be sold later from the makeshift kitchen in the hallway outside the bedroom. Her son dawdled around.

“This company is pushing us into unemployment and poverty, slowly,” Chander said.

Burden of rules

Launched in 2014 by engineering graduates, Urban Company is one of the most popular home service providers in India, enabling users to book beauticians, repairmen, painters, and other professionals. The company’s strength has always been that it simplified and diversified an everyday search. As co-founder Abhiraj Bhal once told YourStory, “All of us have at some point faced issues in finding the right plumber, electrician, or beautician, and in getting them to provide us services at a needed time.” It was this gap that Urban Company filled. But while it might have simplified the lives of its users, it didn’t meet the expectations of all its workers, at least in the beauty segment.

In early 2020, several beauticians say, they felt the company’s commissions rise. Company figures show that roughly a quarter of partner earnings in the salon and spa categories go towards commissions and fees, another 8% towards travel, and 17% towards product purchases. In general, partners earn Rs280 to Rs300 an hour after commissions, product payments, and travel costs.

Partners were required to maintain credit in their account to accept a booking and the company would deduct its commission upon the acceptance of a job, according to the protesting beauticians. If a partner cancelled a booking or was late, she was penalised. According to these beauticians, the fine increased, beginning in 2020, from an average of Rs200 per booking to sometimes Rs800.

While it was always mandatory for partners to buy products they use in their work from the Urban Company store, at some point, the company began sending these products to the partners without their consent. The company admitted as much in its blog post on policy changes in October: “Moving forward, for any new product launches, deductions will be made after the products are delivered to partners and post their consent.”

Such demanding rules were one reason partners like Chander became disillusioned. Chander limped through the two pandemic-induced lockdowns, even servicing three customers infected with coronavirus, she says. One of them told Chander she was “no longer contagious” since it was her 11th day of quarantine. Another told her she wanted to get waxed in case she had to quarantine.

“The customer has all our details,” Chander said. “What details of theirs do we have?”

In August, Chander found herself trapped in a stairwell with men claiming they were taking her to a female client. Fortunately, Chander’s husband, who had driven her there on a motorcycle, helped her escape. It took her 20 minutes to speak to a customer service representative, she says. Yet, she says, she has not heard of any action taken by the company so far.

A blog post by the company spoke of an emergency helpline. But several beauticians say the company no longer assigned managers as nodal officers for booking coordination. For complaints too, partners mostly communicate through a call centre. “We speak through the call centre just like our clients,” Chander said. “There is no one to help us.”

This reporter made several attempts to speak to Urban Company officials, but was unsuccessful. Both co-founder Abhiraj Bhal and a company spokesperson pointed to a set of blog posts. A detailed email questionnaire sent to the company went unanswered.

Litany of grievances

Urban Company and other firms involved in the Indian gig economy take pride in improving the country’s employment outlook. “In the absence of organised players, the market was controlled by middle-men and aggregators, who restricted market access and kept a lion’s share of the margins,” a blog post by Urban Company read. “We believe we have made the industry more transparent, reduced the number of middlemen, and given a voice to the hitherto voiceless informal labour.”

In a country with low female workforce participation rates, the company boasts of a 40% female workforce. In 2020, beauty and wellness services accounted for 55% of its revenue (pdf), and its female workforce is growing faster than its male workforce. In November, a senior executive said the pandemic had accelerated its plans to push the beauty segment. Academics call this phenomenon the “feminisation of casual labour” or “pink collar work.” A study says the majority of Urban Company’s beauty workers are non-migrant, married women (pdf) with children, who are looking for flexible work hours.

Seema Singh was part of this workforce till the first week of January, when she finally quit. Four years ago, she had shut her salon in Laxmi Nagar, Delhi, when an Urban Company representative called her about an opportunity for flexible work.

In the beginning, she had few complaints. She says the earning was respectable and only Rs5 was levied as a late fee. “But then, they got into the habit of eating into our income,” Singh said from her two-bedroom flat in Vaishali, Delhi, while preparing her children for tuition classes in November. Every March, she claims, the company would inform her that she hadn’t purchased the number of products required for completed bookings.

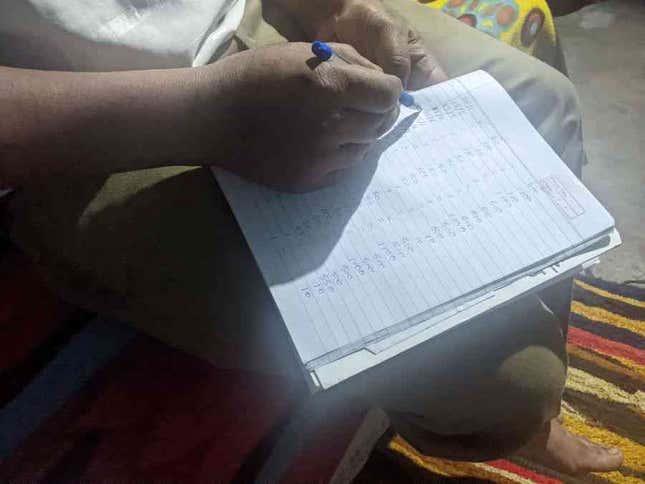

Anjuli Singh had a similar complaint. A beautician partner with the company since 2019, she says, she would add credit to her account to accept a booking, only to find that the company had deducted from it as payment for products she hadn’t ordered. Her husband, Inderjeet, who sat next to her in their apartment, pointed to a diary in which they had tabulated product payments. The total: Rs18,000.

Anjuli Singh says sometimes she couldn’t accept a booking because the mandated products hadn’t reached her, or because she wouldn’t earn enough after paying for the travel, products, and commission. “Why should we be forced to take every booking?” she asked. “Many women, like me, joined because we wanted flexible work. Now you have taken that freedom away.”

As the litany of grievances got longer, Seema Singh created WhatsApp groups at the end of 2019 with other Urban Company beauticians so that they could share their stories. From the messages, it was clear that there was some dissatisfaction with the work conditions. So, on Aug. 2, Seema Singh led roughly 10 beauticians to the Gurgaon office of Urban Company. She says Bhal invited them in, discussed their concerns, and promised to address them. Since Urban Company didn’t speak to this reporter, the meeting could not be corroborated.

Soon after, five beauticians, including Seema Singh, met in Preet Vihar and collated a list of demands. These included a 20% cap on commissions, customer ratings, a better grievance redressal system, quality health insurance, changes to the ratings-based ID-blocking system, and a reduction in product prices. Also on the list was an end to TDS (tax-deducted-at-source) deductions, penalties for up to five cancellations a month, automatic product payments, and additional charges for re-joining after a break.

The demands were approved by other beauticians on WhatsApp and then submitted by roughly 10 beauticians at the company’s Green Park office. Seema Singh claims officials promised to address the demands by mid-October, but nothing changed. Getting restless, the beauticians began planning a protest on the WhatsApp groups, which included Urban Company officials aside from partners.

On Oct. 5, Seema Singh says, she received a phone call from a woman who she knew as a general manager at the company. On the call, the manager said in Hindi, “If you instigate women again, bring them to the office again, I will not speak to anyone.” This reporter heard a recording of the conversation.

Seema Singh urged the caller to reduce the commission and product prices, with the caller replying that the company had agreed to some of the beauticians’ demands. The caller also maintained that the commission hadn’t been increased in years. Then the caller asked Seema Singh how much she worked. She answered two bookings a day.

“Those who take two bookings won’t be able to save [money],” the caller retorted. “You will need to do three bookings [a day]… If you don’t want to do this work, then leave it. If you want to do less than 20 bookings a month, don’t join the platform.”

A frustrated Seema Singh said, “You didn’t say this before. I left my job because of what you said at the time…You said, ‘Do as much work as you want.'”

“Now I am telling you what has changed…,” the caller said. “The thousands of demands you are taking from me…First, you stop being a politician. I am ready to listen to everyone’s individual problems.”

First confrontation

Meanwhile, in early October, just as Chander recovered emotionally, she says, the company told her she would be blocked from the platform unless she underwent re-training—a six-day affair. Such re-training, the beauticians say, used to happen in the past as well but was mandated for those partners whose rating fell below 4.2 out of 5. Now the cut-off had been upped to 4.7 in the salon category, they claim. “How will I afford (to take) six days (off from work) for retraining?” asked Chander.

It was this re-training and rating pressure that, beauticians say, pushed them over the edge. “The women had been discussing a strike for a while,” said Chander. “But since many are widows and single mothers, they were scared the company would block them. I think after hearing about my situation and my suicidal thoughts, they got courage. They thought, ‘If not now, then never.'”

Before the strike, the beauticians say, they received a video featuring two women who identified themselves as managers at Urban Company. One of them was the general manager who had earlier called Seema Singh and discussed her workload. “We have heard that some partners are pressuring others into not working,” said one of the managers in the video. “We want to tell you that you don’t have to fear them…For your safety, we have spoken to the Gurgaon police. If anyone hurts you for carrying out your work, then police action will be taken against them.” This reporter saw the video.

The strike went ahead on Oct. 8. In the morning, roughly 100 women, most of them in their Urban Company uniform, showed up outside the Gurgaon office for a day-long protest. Videos of the agitation show beauticians shouting slogans, company officials trying to reason with them, and police officers standing by. On that day, “those managers who had never listened to the girls’ problems before were calling us to lunch (with a co-founder),” said Seema Singh. “That day they unblocked several IDs.”

On Oct. 14, the company invited roughly 15 women to the Gurgaon office. Among them was Gunjan Chaudhary, an Urban Company partner of four years. At the meeting, Chaudhary says, the company gave the women T-shirts, water bottles, and a diary. “I laughed, I didn’t take any of it,” she said.

Since the company did not speak to this reporter, what happened at the meeting could not be corroborated. But, according to Chaudhary, officials at the company said they had met the beauticians’ demands. In Chaudhary and Seema Singh’s telling, the 35% commission on larger bookings was reduced to 25%, but the 5% commission on smaller bookings was raised to 8.5%.

On the same day, the company announced a “12-point programme to improve partner earnings and livelihood.” Algorithmic blocks on partners were lifted, service pricing was improved, commissions were capped at 25%, penalties were limited to a maximum of Rs1,500 a month, the rating mechanism was revised, and entire cancellation fees were to be paid by customers was promised to the partners.

Legal course

This commitment resolved some issues, but clearly not all. “They’ve brought in another rule just to kill us further,” said Chander.

In early December, a video was shared by the company that described a new working structure. In this video, a man who identified himself as a general manager said that moving forward, all partners would be grouped into two categories: those who work regularly and those who don’t. The partners who meet certain requirements over a testing period and work regularly will be sent bookings often, he said. Meanwhile, those who fail the requirements will be sent bookings only on “peak days” like weekends.

Thrown by the new programme, Seema Singh and Chaudhary visited the Gurgaon office on Dec. 13 to complain. But, according to Seema Singh, nothing came out of the meeting. On Dec. 20, they protested again outside the Gurgaon office. A couple of days later, the company filed a lawsuit, in which it named Seema Singh, Chaudhary, and two others.

While the women had no union representation in the runup to the strike, they have since been urged to join the Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers and the All-India Gig Workers Union. They say they have been seeking advice from the unions.

“If they want to bring in a lawsuit, then we can also stand up,” said Shaik Salauddin, national general secretary of the Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers. “They may have their policies, but we have the Constitution, which gives the right to protest. These women have laid out their carpet in front of their office in the cold, but the company doesn’t have any empathy for them.”

The lawsuit states that the company is only an “aggregator” connecting customers to service professionals who are “independent workers” that “voluntarily work” and are “free to decide when and where they wish to work.” It argues that a “certain group of disruptive partners…have decided to repeatedly derail the collaborative and cooperative process for their unknown ulterior motives and vested interests.”

Furthermore, it says that some protesters in September harboured “an intent to cause damage” to the company’s property and personnel and that the WhatsApp messages in the runup to the October protest “instigated other partners to take up violence.”

“The company knows we have nowhere else to go,” Chander said. A salon won’t hire “Urban Clap girls” like her because they have developed a reputation for stealing clients, she says. “That’s why they have taken advantage of us,” she said. “Now I don’t know if the girls will stand up so quickly again.”

*Name changed on request to protect identity.

This piece was originally published on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].