A scene in the recently released film, The Kashmir Files, shows a Hindu woman being stripped and sawed alive by militants in the 1990s as her Muslim neighbours looked on.

All it took to recreate this scene in Madhya Pradesh’s Khargone was a mannequin borrowed from a store, a pile of wooden logs to evoke the setting of a sawmill, and a bicycle wheel to stand in for an electrical saw, said Raju Sharma, the district president of Shiv Sena, who had sponsored the jhaanki, or tableau, as part of the Ram Navami procession in the town on April 10.

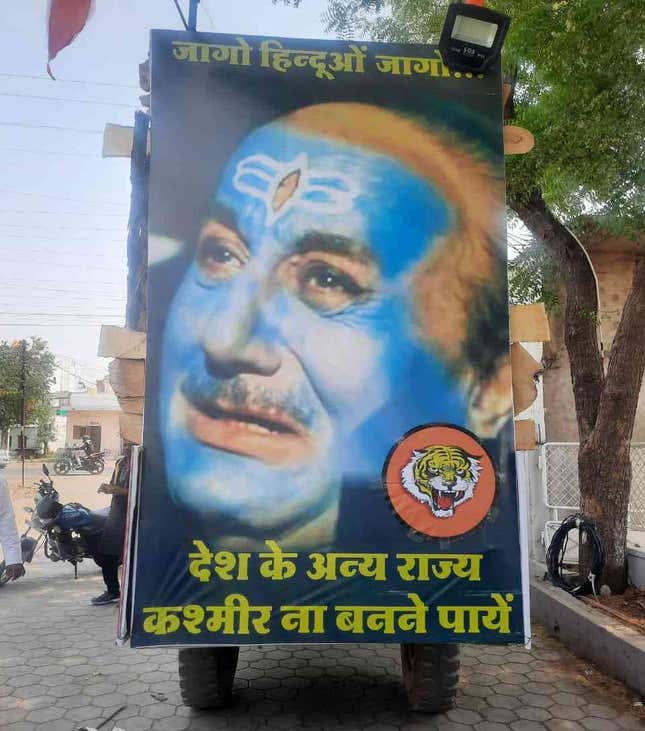

The installation was placed on a tractor-trolley. Its back displayed the distraught face of actor Anupam Kher, who plays the woman’s father-in-law in the film. Alongside was a warning in bold text: “Wake up Hindus, lest other states in India become Kashmir.”

To maximise the impact of the installation, Sharma, who owns a sand supply business, got a friend to mix the woman’s sobs from the film with a music track featuring belligerent cries of “Jai Shri Ram” and “Har Har Mahadev.”

On Ram Navami, celebrated as the birthday of Lord Ram, this soundtrack became part of a high-decibel cacophony at Talab Chowk, a town square framed by the minarets of a mosque, where Hindu groups had been given permission to assemble at 2 pm, before proceeding on a tour of the town.

Instead, three hours later, at 5 pm, when Muslims gathered at the mosque for the evening Asar prayer, the procession had still not departed, several eyewitnesses said. Videos show disc jockeys blaring raucous music as thousands of Hindus—mostly young men—spilled over from the chowk into nearby lanes. Some waved flags of “Ram Rajya”, or the rule of Ram.

Suddenly, stones began to fly—Hindus claim they came from a lane behind the mosque, Muslims say members of the procession first threw them at the police.

By 6 pm, rioting and arson had broken out in several neighbourhoods of the town. Near the masjid, Siraj Bi bolted from her tiny house as a mob set it on fire. The elderly widow weaves garlands for a living. Among her belongings scorched that day were clothes she had stitched for her daughter’s dowry.

Two km away, in Sanjay Nagar, Nannu Bai Bhandole too ran for her life as flames engulfed the front part of the house that she had painstakingly built. The autorickshaw that the Dalit woman’s son had purchased on a loan was reduced to a burnt carcass.

The next five hours brought a steady stream of injured people to the Khargone district hospital. One of them was 16-year-old Shivam Shukla, who sustained head injuries and had to be moved to an intensive care unit in the nearby city of Indore. The same night, a body landed in the local mortuary with wounds all over. Four days later, it was identified later as 28-year-old Ibraish Khan.

Communal violence is not unusual in this hardscrabble town of about 125,000 people, over 60% of whom are Hindu, the rest Muslim. In recent years, festival processions of both communities appear to have become DJ-soaked displays of male aggression.

The Ram Navami riot was not seen as worthy of front-page news in India—after all, Khargone was just one of many places in the country that had seen the violence that day.

But what followed the next morning grabbed even international attention.

On the morning of April 11, Madhya Pradesh’s home minister told reporters in the state capital: “The houses of those pelting stones will be turned into a pile of stones.”

By noon, while Khargone was still under curfew, bulldozers came crashing down on the modest single-room home of Hasina Fakhroo built on government land using Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, or prime minister’s housing scheme funds. The front of Javed Shaikh’s chemist shop, housed in the compound of the Talab Chowk mosque, was shaved off. A tin-shed kiosk of a disabled man, Wasim Sheikh, was flattened.

According to a document that a senior official of the state home department sent to reporters in Bhopal, 49 properties were demolished in Khargone that day. All were owned by Muslims.

More demolitions followed the next day—even the affluent were not spared. A five-storey hotel owned by the family of Alim Shaikh, a former Congress corporator in the city, was hollowed out. “The administration claims the hotel front was jutting out on the road, but so were the buildings next to us,” said his cousin, Shahid Khan. “Why were they spared?”

The administration maintains the demolitions were part of a routine “anti-encroachment drive”. But two senior officials who spoke to Scroll.in on the condition of anonymity, admitted they were done to “restore peace” and “control the situation”.

As one put it, the “Hs” (shorthand for Hindus) were convinced that the “Ms” (shorthand for Muslims) had first attacked their religious procession, then their homes and properties, as part of a larger design. “Therefore, we identified the areas where rioting had taken place and targeted the encroachments there,” the official said.

“There was a lot of pressure,” said the second official. “People were saying yeh todo, wo todo”—break this, break that. “But the administration only went for what was illegal.”

Many property owners dispute the allegations of illegality. They say they had not been served notice as required by law. District collector Anugraha P denied this. But when asked for a copy of the notices, she told this reporter to file a Right to Information request.

In response to a question about whether action had been initiated against the organisers of the Ram Navami procession for prolonging their stay at Talab Chowk, she said, “More than half of the gathering had already moved forward.”

The Khargone demolitions have now inspired copy-cat action in Gujarat and North Delhi—like Madhya Pradesh, on the orders of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party. This has deepened Muslim fears around the country, of first being provoked, and then being punished.

But what is even more chilling is that the demolitions haven’t doused Hindu anger in Khargone—instead, The Kashmir Files continues to inflame passions.

Lopsided action

Past sundown on April 23, a cavalcade of cars wound down the lanes of Tawadi Mohalla, an inner-city neighbourhood of Khargone where Hindus and Muslims live in close proximity to each other. It was nearly two weeks since the riots had erupted, but an evening curfew was still in place in the town.

As the cavalcade stopped, the district collector stepped out of one of the cars. She walked up to a house and handed a compensation cheque to its riot-scarred residents—an elderly Muslim couple.

It was only when she reached the second house – home to a Hindu family – that I noticed a man with a BJP stole around his neck. He was Khargone’s member of Parliament, Gajendra Singh Patel. He had skipped meeting the Muslim family. Through the evening, he only visited riot-hit Hindu homes.

Although Nasir Ahmad had heard the sounds of the official cavalcade in his neighbourhood, he had not stepped out of his house. The former assistant sub-inspector of police later told me he knew the BJP MP was there to hear only one side.

Two nights later, Patel validated Ahmad’s suspicions as he declared to a Hindu gathering in a nearby village that those who had thrown stones instead of flowers at “Ram Ji’s procession” would need to be prepared for “bigger stones” coming their way. His speech went viral.

Ahmad, the former policeman, lives in a predominantly Hindu corner of Tawadi Mohalla. He said he saw his next-door neighbour throw stones at his house. His nephew even recorded a video of Hindu rioters amassed on a nearby roof, before their stones forced him to duck for cover. As the rioting intensified, petrol bombs burst in the compound of Ahmad’s house. Three motorcycles parked there were incinerated.

A few days later, when an official team came to survey damages, Ahmad stepped out to meet them but a policeman blocked his way. “He abused me, hit me with a baton 4-5 times,” he said, “worse than I ever hit a criminal.”

Ahmad had served nearly four decades in the police force, but it took him over a week to get a First Information Report registered.

At the Khargone police station, an officer said 71 FIRs had been registered so far. Scroll.in saw a list of 52, all based on complaints made by Hindus against Muslims. Altogether, 175 people had been arrested in the town. Barring 14, all were Muslim.

In Teba Nagar, Shabana Khan’s husband Hakim Khan had been prescribed surgery by the district hospital to remove a painful callus on his foot. He could barely walk when he was arrested by the police, she said.

Rioters had slashed Mehrun Khan’s face with a sword in Anand Nagar, before they entered and looted her house. She preferred to lie bleeding all night than head to the hospital with the police. “What if they threw me off somewhere?” she asked.

The family has now moved to another part of the town – fearing not violent mobs, but the police. “I could get arrested,” her middle-aged son said.

The family is yet to receive any financial assistance from the administration – even for Mehrun Khan’s treatment costs. Her daughter-in-law took her to the tehsil office to file a compensation claim on April 23, but they returned without any success.

A tale of two Amjads

Much of what transpired in the days following the Ram Navami violence followed a familiar pattern, said Altaf Raja, who serves as the Muslim community’s representative in the town.

Wary of the police, Muslim riot-victims avoided going to the police station to file complaints, he said. This meant official tallies reflected more losses on the Hindu side, and more criminal cases against Muslims. The media played videos of Muslim rioters on a loop while blanking out videos of Hindu rioters, further amplifying Hindu anger.

All this was familiar, said Raja. What was new were the demolitions.

Amjad Khan, who runs a 400-employee, three-unit strong business that makes and sells biscuits under the brand name “Best Bakery”, gave a vivid account of the arbitrariness at play.

A well-known face of his community, Khan said he is often roped in by the police to help maintain peace in the town.

On the day of Ram Navami, on the request of the police, he stood outside the Talab Chowk mosque, asking Muslim boys to disperse. “You don’t need to watch the procession, I told them,” he recalled.

After the clashes broke out, Khan said he spent the next three hours combing the lanes of Khargone. “A fire vehicle was passing by, Muslim boys threw stones at it. I cursed them and said, this is going to douse the fires, why are you targeting it.”

But the next day, when he went to the police station, policemen told him that he had been spotted in CCTV footage from riot-hit areas. “Tu dikh riha hai”—you can be seen—hey said. “Main dikhunga”—I will be seen—he replied.

He reminded them that he had been enlisted by no less than the police station in charge and the sub-divisional police officer. “I was supporting the police at risk to my own life.”

But a constable dismissed his pleas: “Now you will go to jail. Your home and bakery will be demolished.”

At 8 am the next morning, the chief municipal officer phoned him, asking him to send official documents related to his business over WhatsApp. “I had everything, from No Objection Certificate issued by the municipality, to GST registration,” he said. “My units are built on land that I own. I have followed every single norm.”

Soon, a municipal team arrived outside his properties to take measurements. Khan panicked. He asked his wife and children to pack up their jewellery and valuables and leave the house, while he rushed to the police station. This time, he met the additional police superintendent, in the presence of the sub-divisional officer, who vouched for his role as a civil police volunteer, he said.

The additional police superintendent then asked Khan to follow him as he drove down to his bakery. By then, the bulldozers had already arrived outside the three units, with top officials in attendance—the chief municipal officer, the district collector, the divisional commissioner of Indore.

According to Khan, the police officer took the municipal officer aside and briefed her. “The CMO ma’am then told her team, spare his home and two bakeries, demolish only one,” he said. When he asked her why, she said he did not have the requisite building permission for it. Besides, it violated the MOS, or marginal open space norm. When he contested this, he claimed, she cast a downward glance and mumbled that it was the police that had given them his name.

The chief municipal officer did not respond to a question about Khan’s allegations. The additional police superintendent confirmed he had visited the demolition site and had spoken to municipal officials about Khan, but when asked for more details about the conversation, he said, “the police have nothing to do with this”.

Amjad Khan is convinced that he was targeted because of mistaken identity. He pulled out a newspaper clipping that summarised the complaint of a Hindu man who had identified an “Amjad Khan bakerywala” among the rioters who had burnt his house. “Although the report says this Amjad Khan is a resident of Qazipura, the police mistook me for him.”

Hours after the bulldozers pulled away from Best Bakery, they landed up outside Super Bakery run by the other Amjad Khan. Freshly-baked biscuits were ground to dust under the weight of falling concrete and metal.

Fearing arrest, Super Bakery’s owner is now on the run. His wife, Ameena Khan, estimated that their losses exceeded Rs 30 lakh. “We had never been given any notice,” she said.

Mysterious fires

It isn’t just municipal bulldozers that have targeted the properties of affluent Muslims in Khargone. In the days after the riots, fires broke out at three industrial units on the outskirts of the town – an automobile repair unit, a bone-meal factory, a plastic recycling unit.

Arif Sufi, a young first-generation entrepreneur, had set up the plastic recycling unit in 2015. His father, a retired government employee, had broken his fixed deposits and his mother had sold her jewellery to fund his initial investment.

Eight years later, Sufi’s business was clocking an annual turnover of Rs 60 lakh – before a fire reduced it to a worthless heap on April 16.

Sufi fought back tears as he recounted the shock he experienced when he heard from locals that four days after the riots, a group of men had come to the industrial area to identify Muslim-owned factories.

“I have been targeted just because of my religion,” the 31-year-old said. “If the plan was to cause me economic harm and break my will, then I want to ask if the will of so many people is broken, how will the country progress?”

“Khargone Files”

Despite the mounting losses of Muslims, Hindus in Khargone are still seething with anger. “Just like The Kashmir Files, they [Muslims] are out to make Khargone Files,” said Mahesh Muchhal, a Bajrang Dal worker, whose home was torched in Sanjay Nagar.

This is now a commonly heard sentiment in the town, even among those who did not suffer losses in the riot. It rings eerily similar to the statement that Kapil Mishra, a BJP leader from Delhi, made in Bhikangaon, 50 km from Khargone, on the evening of Ram Navami. He said if Hindus did not draw lessons from The Kashmir Files then one day similar films would be made about Delhi, Bengal, Kerala, for that matter, even Khargone.

Mishra’s presence in Bhikangaon, coupled with the size of the gathering – 14,000 people, according to a senior police officer – had forced the administration to divert a section of the police force away from Khargone that day. “We feared something could happen there, instead it happened here,” the officer said. Only after the riot, he said, did he realise that The Kashmir Files was being avidly discussed in the town.

As it happens, the Ram Navami violence has now validated the fears that The Kashmir Files stoked. In a Hindu-majority town, local Hindus now see echoes of Muslim-majority Kashmir—more accurately, the version shown in The Kashmir Files that portrays Muslims as a blood-thirsty community that wholeheartedly supported militants as they raped and killed minority Pandits and forced them to leave the Valley.

“Even my nine-year-old granddaughter now fears rape,” Rajendra Parsai, an elderly man, shouted in anger as he accosted the BJP MP while he was making a round of Hindu neighbourhoods on April 23.

Instead of allaying these fears, the state BJP government is reinforcing them. Agriculture minister and district in-charge Kamal Patel said in an interview, “What was shown in The Kashmir Files has happened in Khargone.”

When the film was released in March, the entire top brass of the BJP, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, had endorsed it. Madhya Pradesh chief minister had granted half-day of leave to policemen to watch the film. In Khargone, leaders like Raju Sharma had organised free shows of the film.

“All this was done to create a mahaul,” said Idris Shaikh, a daily-wage worker. “Samaj ke har tabke ko film dikhayi gayi.” Every section of Hindu society was shown the film.

Nannu Bai Bhandole’s son, Amit, hadn’t watched The Kashmir Files but after his house was scorched in the riot, he has now grown curious about it. “They say just like Hindus were forced to leave Kashmir, we will be forced to leave Khargone,” he said. Already, Muslims had purchased the two houses next to his, he reasoned.

One of them was locked. On the wall of the other, a sign had been scribbled in chalk: “This house is up for sale.”

Inside, Wahida Khan, who sat wielding tailoring chalk on fabric, explained: “This time, our side burnt their houses, next time, their side will burn ours. It is better for us to leave.”

This piece was originally published on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].