State governments in India are going door-to-door, or rather roof-to-roof, to solve their acute and recurring power problems. The new central government has pledged to light at least one bulb in every home with solar energy by 2019, making rooftop solar an idea whose time has finally come.

Karnataka, the largest southern state by area, just announced its new solar policy as temperatures reach records during this year’s blistering summer. The government plans to buy energy from homes and public buildings that generate power from rooftop solar panels connected to the power grid.

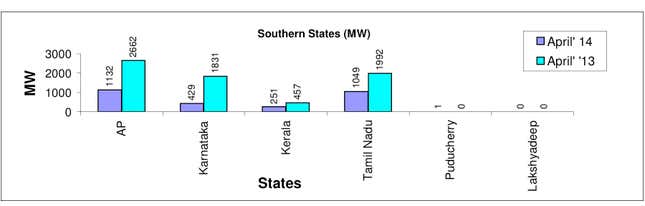

The state needs the help—Karnataka had a shortage of more than 400 megawatts of power in April. Bangalore, the state’s capital, had to power cuts every two hours in the blisteringly hot months of April and May.

Of course, power cuts are common during the hot summer months, thanks to an overall energy shortfall of more than 42 billion kilowatt hours, or 42,000 gigawatt hours. The 2012 power outage that left an estimated 600 million people without power may have been the most widespread and internationally reported, but at any given time millions or tens of millions are without electricity in India.

With 300 sunny days a year, Karnataka has 10 gigawatts of solar energy potential. The new policy will add 2,000 megawatts (2 gigawatts) to the state’s power kitty, if all goes according to plan, and rooftops alone will contribute 400 megawatts by 2018.

A residential rooftop in India typically ranges between 200 and 1,000 square feet, meaning it can comfortably house a standard one-kilowatt solar photovoltaic system. The Energy and Resources Institute estimates these systems can cost as little as Rs 110,000 ($1,850).

Households can use the power generated by their solar arrays (the average household needing 200 units of electricity a month will use about 80% of an array’s daily output) and the government will buy the surplus.

House-to-grid transactions around the world follow a well-established net metering system, in which a solar-powered home can either sell its surplus energy to the grid or buy energy from the grid if it needs it. But the net metering system has its own hurdles, mostly in the form of disgruntled utilities, who have watched their consumer bases shrink.

Net-metering led to a stand off in Arizona last year, after utility companies complained that it did not account for their large grid infrastructure costs. Ultimately grid-connected power consumers who had installed solar power panels had to pay an additional fee.

Before India reaches that point, there is a more fundamental question to be asked—will there be enough homeowners willing to install rooftop solar?

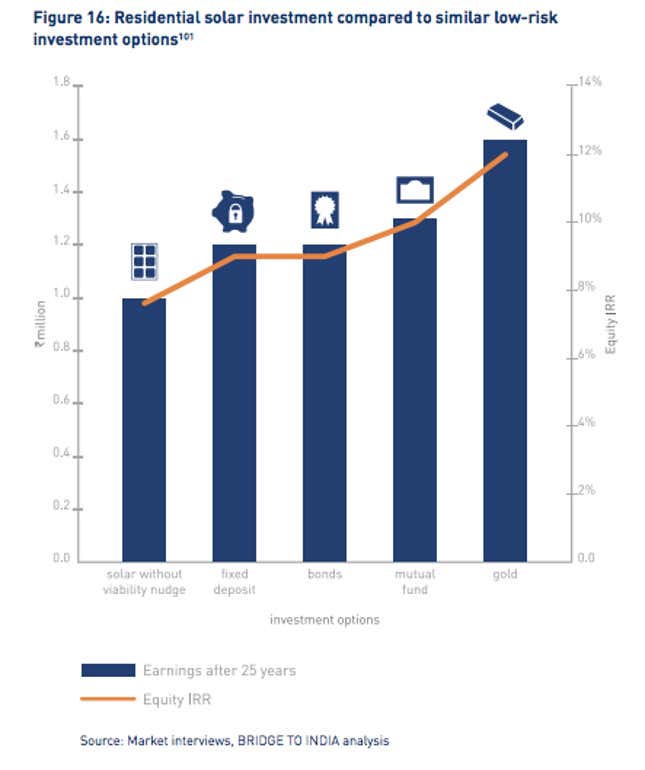

Sure, power prices in India have been steadily rising in recent years, driven by rising coal and diesel costs and poor investment in infrastructure. But a Greenpeace study of rooftop solar potential in Delhi finds that between falling solar panel prices and rising grid tariffs, rooftop solar is an attractive proposition for commercial, industrial, and government customers—but may not be attractive to the average homeowner.

Making matters worse, a proposed tax on solar panel imports, designed to protect India’s manufacturers, could make solar programs even more expensive if it is enacted.

To kickstart residential rooftop solar, Karnataka’s neighbor Tamil Nadu is offering a combination of subsidies and incentives that allow the purchase of a rooftop solar power system costing Rs 1 lakh ($1,700) for half the price.

Prime minister Narendra Modi’s home state of Gujarat has generated 1.2 million kilowatt hours of solar power from a rooftop solar project in the capital Gandhinagar. Here, property owners are given “green incentives” to aid the project. Solar developers hire terraces to set up their arrays and pay the owners Rs 3 for every unit of energy they generate. The developers sell that energy to the state’s power provider via the electrical grid.

Delhi drafted a rooftop solar policy in 2011 that never really took off. Diesel was still cheap back then and the government couldn’t crack the economics of solar power. The city is now seeking inspiration in Gandhinagar’s rent-a-roof scheme.