The presence of female officers in police stations can make access to India’s justice system easier for women in a country known for high rates of gender-based violence, the findings of a study suggest.

India ranks 140 out of 156 countries on gender equality according to the World Economic Forum. India has also, over the last 20 years, shown a high and increasing trend in domestic violence against women.

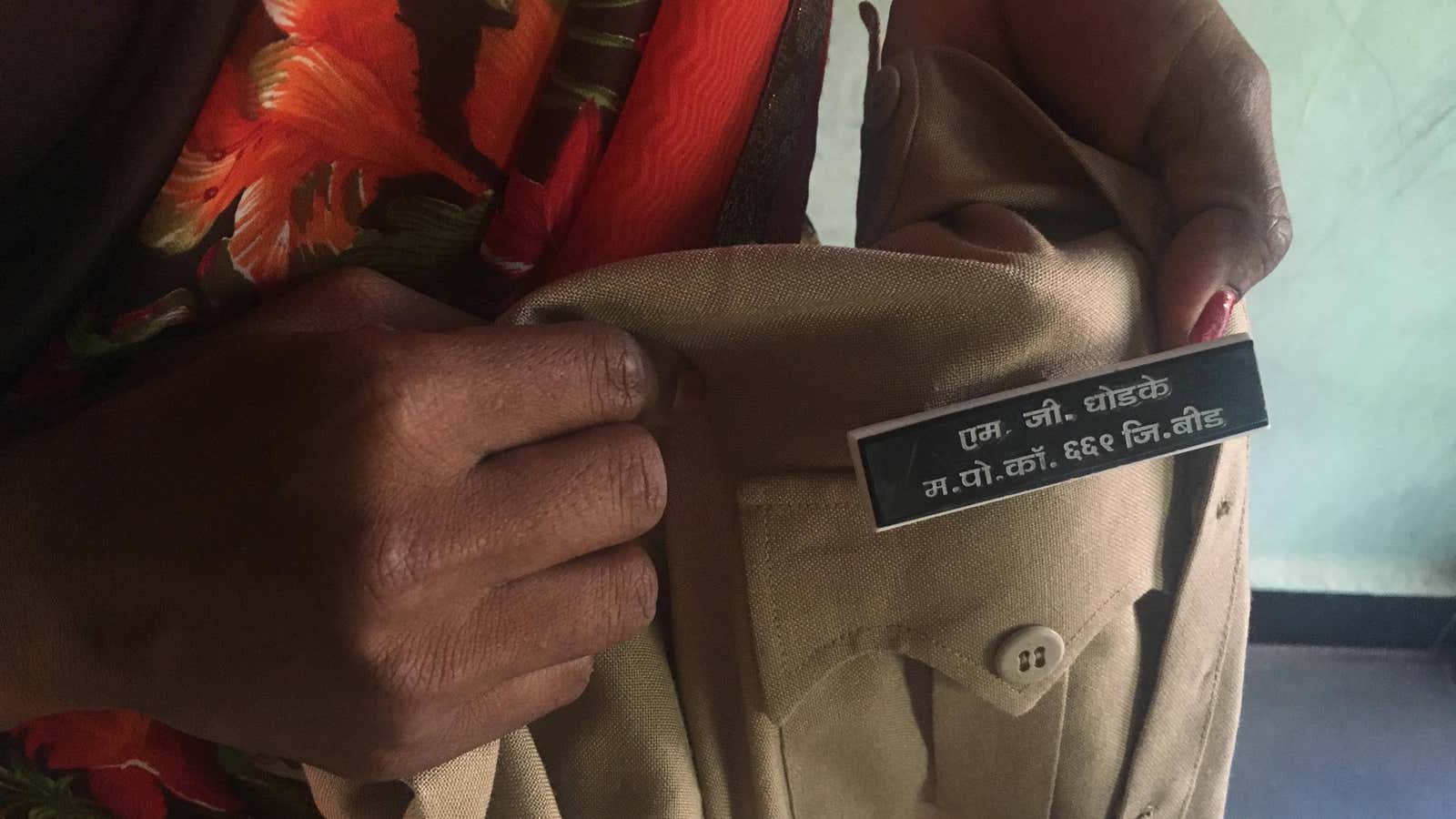

The study, published July in Science, is based on a sample of 180 police stations serving 23 million people in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. These 180 stations were randomly assigned into three groups—61 of them had regular women’s help desks, 59 had help desks run entirely by women and 60 were designated as control with no help desk.

In India, case registration, in the form of lodging officially a first information report at a police station, allows a police officer to make arrests without a magistrate’s warrant and initiate criminal proceedings. Case registration can also be through a domestic incidence report, which initiates civil proceedings under the supervision of a magistrate.

Over the 11 months of the study, police stations with help desks registered almost 2,000 more domestic incident reports and over 3,300 more first information reports than stations with no help desks. The increase in first information reports that led to criminal proceedings was driven entirely by help desks run by female officers.

“The substantial increases in case registrations—both civil and criminal—as a result of this intervention shows that given the right support and training, the police can indeed be responsive to women,” Sandip Sukhtankar, an author of the study and associate professor at the department of economics, University of Virginia, US, tells SciDev.Net.

Women in India face major obstacles to case registration, says the study. “Even when a woman overcomes social and familial pressures to report a case, officers often resist officially recording it—despite their legal obligation to do so.”

Sukhtankar says that registration of cases is a small but important step in achieving justice for women victims of crime, adding that more effort would be required before women are comfortable approaching the police with complaints of criminal or civil offences.

Meera Khanna, secretary of the Guild for Service, a non-government organization that works for women’s empowerment and has consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council, says that crimes against women are generally not registered by police because of the patriarchal nature of Indian society and the failure to effect police reforms as mandated by the supreme court 15 years ago.

“The socioeconomic background of ordinary policemen, including those in charge of police stations, is such that they tend to belittle crimes against women, the majority of which are sexual rather than economic in nature,” says Khanna.

“A typical policeman would consider murder to be a crime far worse than rape,” she adds. “But the attitude of a policewoman can be expected to be different as she understands better the magnitude of rape as a crime—because the fear of rape is a shared experience for all women.”

When women report crimes, the police are often dismissive, guided as they are by patriarchal norms, says Khanna. “The result is that the female complainant ends up getting re-victimized.”

Khanna says that while she is happy to learn that the police in Madhya Pradesh plan to introduce women’s help desks in all the 700-odd police stations in the state, improving access to justice for women in a large and diverse country like India is bound to be slow and patchy.

One sticking point is the role of the police. According to Khanna, the force suffers from a “colonial hangover” and still sees its primary function as maintaining law and order and providing protection to politicians or high officials rather than investigating crime.

“The findings provide concrete and actionable insights to policymakers working toward reducing violence against women,” says Shobhini Mukerji, executive director in South Asia of the Crime and Violence Initiative of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, a major funder of the study along with the World Bank’s Sexual Violence Research Initiative.

Crimes against women are a major obstacle to development, especially in low- and middle-income countries, adds Mukerji.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk. We welcome your comments at [email protected].