Among other prickly bilateral issues, India’s new foreign minister, Sushma Swaraj, is expected to work toward resolving disputes along the country’s border with Bangladesh on her visit to Dhaka.

The 4,000-kilometer-long boundary is unlike any other. Straddling over 150 enclaves—small parcels of territory completely surrounded by the other country— and barbed-wire fences running besides shifting riverbanks, it has caused much friction between New Delhi and Dhaka.

The remarkably porous border is also the reason why India and Bangladesh have flourishing informal trade—which may be almost as big as the formal bilateral trade between the two countries.

Informal trade in this region typically involves illegal transactions with the participation of local residents and enforcement agencies, either through small-scale bootlegging or larger smuggling syndicates.

And as with most shadow economies, exact numbers are difficult to discern. In 2009, Bangladesh’s high commissioner to India estimated that informal exports from India were about as large as formal exports at $4 billion.

A few years earlier, the World Bank reported (pdf) that “Bangladesh’s smuggled imports from India during 2002/03 were approximately $500 million, or about 40% of recorded imports from India, and approximately 30% of total imports (recorded plus smuggled) from India.”

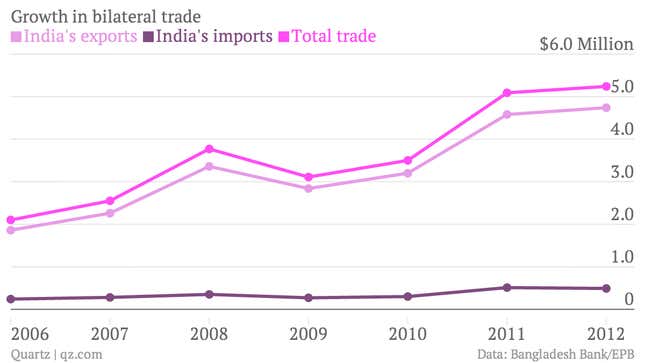

Since then, formal trade between the two countries has exploded, and Bangladesh is now India’s largest trading partner in south Asia. It seems informal exchanges have moved in the same direction.

There are three main reasons behind the robustness of informal trade on the Indian-Bangladesh border, according to a 2003 study (pdf) of the phenomenon:

1. Official machinery is slow and outdated, thereby creating delays and escalating costs

2. Bribes and other demands via government officials add to the transaction expenses

3. An inadequate transport infrastructure, leading to high transit expenditure, creates an incentive for informal trade

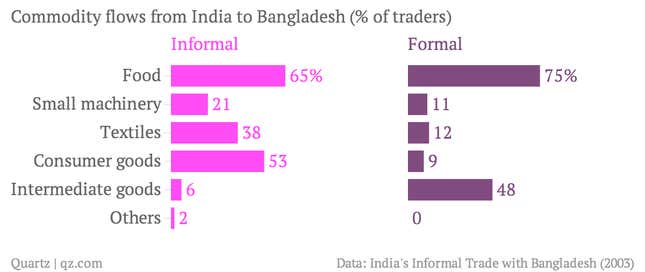

The study, which surveyed 200 formal and informal traders on both sides of the border, also reported that food, consumer goods and textiles were the most popular exports from India.

There is also a booming cattle trade that is worth around $500 million (pdf), feeding off Muslim-dominated Bangladesh’s high demand for beef. Hindu-majority India, on the other hand, has a surplus, although it has banned exports. As a result, 20,000 to 25,000 cattle, worth around $81,000, are thought to be smuggled across the border every day.

During its term, the Manmohan Singh government made attempts to improve bilateral trade by proposing to develop seven integrated check posts, land custom stations and also border haats (temporary markets) to serve border communities.

Of course, the larger issue of demarcating boundaries will be Swaraj’s focus in Bangladesh this week, but both governments mustn’t forget the massive informal economy this border has spawned.