India wants Chinese investments—and it seems to be in a hurry.

Just weeks after Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi met the new government in New Delhi, India’s cabinet has now given “in-principal” approval to a memorandum of understanding allowing China to invest in industrial parks in India.

The details of the agreement are still under wraps, although Indian vice-president and the new commerce minister are currently in China on a five-day visit.

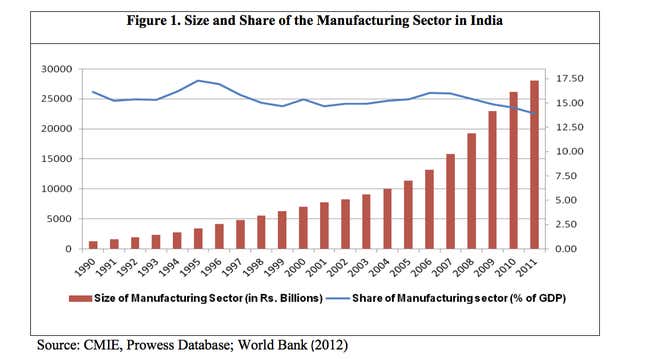

On the face of it, the government’s plan seems reasonable. India’s languishing manufacturing sector urgently needs investments, and with Western economies in disarray, turning to Beijing to kick start things seems rational.

It would also help India bridge its yawning trade deficit with China, currently sized at about $40 billion.

But that’s just on the surface. Here are four reasons why inviting China to set-up industrial parks isn’t such a great idea:

India’s industrial parks (or SEZs, if you will) haven’t exactly delivered

While the details of what the Indian government is proposing still isn’t clear, the past record of industrial parks—including China-inspired Special Economic Zones (SEZs)—is mixed.

Apart from land acquisition, taxation-related issues and infrastructure constraints have hamstrung the projects. It’s led to questions about loss of revenue to the exchequer.

Even commerce minister Nirmala Seetharaman in an interview earlier this month admitted that the entire SEZ policy needs a comprehensive re-look. The government, though, has been careful to leave the term ‘SEZ’ out of this latest plan. So, what exactly are industrial parks then?

The Chinese manufacturing model isn’t what India needs

The Chinese manufacturing mantra, which it has successfully exported to the ASEAN region, doesn’t match India’s requirements.

Large scale, low-cost, labor-intensive manufacturing may make sense for other developing economies, but India is perhaps better off by focusing on higher-value manufacturing.

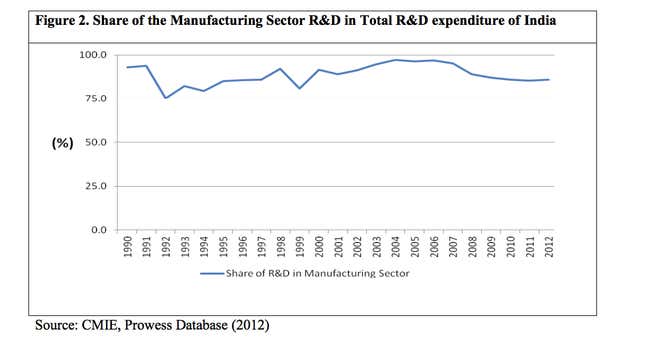

A 2013 Indian Institute of Foreign Trade working paper (pdf) suggests that the dismal growth in India’s manufacturing sector is linked to the lack of depth in technology.

“Most Indian manufacturing firms appear to be stuck at the basic or intermediate level of technological capabilities,” the paper explains, “In India, manufacturing sector is losing its recognition and there is a need to invest more in R&D to make it competitive globally.”

Given the Chinese industry’s reputation for focusing on margins and profitability in overseas manufacturing, it is unlikely that substantial R&D investments will made to upgrade India’s research and production facilities.

India’s workforce isn’t tuned for Chinese firms

Part of the reason why the Indian government wants Chinese investment is to help in job creation. And part of the reason why Chinese companies want to invest here is India’s burgeoning workforce.

But there are fundamental problems.

Unlike in India, Chinese businesses don’t always have to contend with democratically elected governments elsewhere in Southeast Asia. The workforce in India is more unionized, with significant political clout to compared to other countries in the region.

As a result, the Chinese human resource management model, which has led to a rash of protests in recent year on the Chinese mainland and elsewhere, may not perform as smoothly as expected.

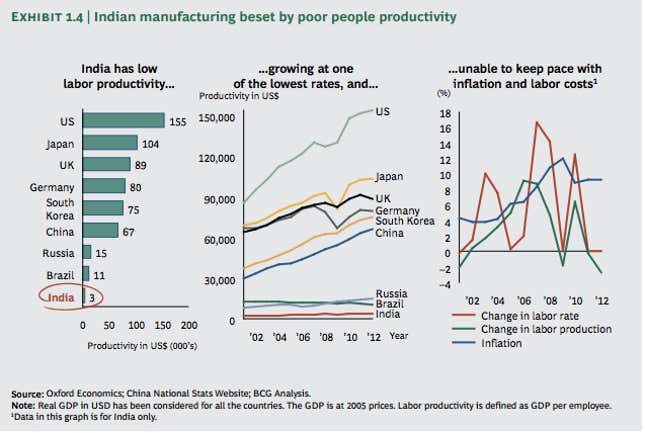

Moreover, Indian labor also has significantly low productivity—particularly compared to China—with very little growth, according to a 2013 Boston Consulting Group-CII report (pdf).

India’s small businesses will hate the competition for labour

The two big challenges for Chinese manufacturing, according to a 2013 Deloitte study, is rising labor costs and increased competition for human resources.

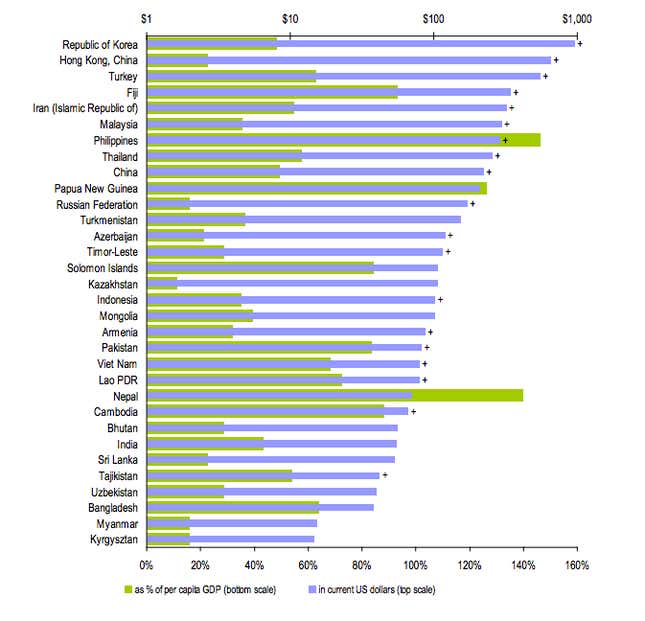

The monthly minimum wage in India, however, remains one of the lowest in region, less than even smaller economies like Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia, according to an UNESCAP study (pdf).

That’s good news for Chinese firms looking to keep costs low.

But that is a threat to Indian companies, particularly small and medium enterprises, who are reportedly concerned about disproportionate competition and dumping of Chinese goods in the subcontinent.