Seen through one prism, the state of the Indian economy can be framed at this delicate point by four headline numbers: one each for public finance, external trade, private companies, and the common man. Two numbers have been contained after threatening to get out of hand. As for the other two, finance minister Arun Jaitley will grapple with them in his budget today as he tries to steer the Indian economy out of the rut it has landed itself in.

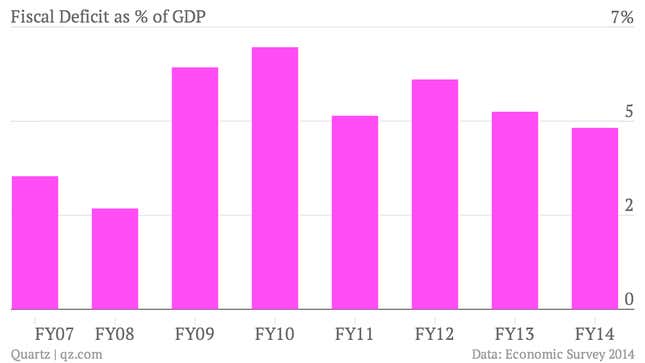

Fiscal Deficit

There’s good news and bad news on this metric that indicates whether an economy is living beyond its means and by how much.

The good news: From a high of 6.5% of GDP (gross domestic product) in financial year 2009-10, the first year of the previous UPA regime in which it opened its purse strings to stimulate demand, fiscal deficit fell to 4.5% in 2013-14, as compared to the 4.8% estimated at the beginning of that year.

The bad news: the quality of that deficit is worrying, as more than 70% of the part that is financed by borrowings went to meet day-to-day expenses, and not to create any assets that will pay back in time.

The 2014 Economic Survey, released on Wednesday, advises the government to introduce tax reforms such as the Direct Tax Code (DTC) and the Goods and Services Tax (GST), which can help reduce the fiscal deficit. The GST, for example, replaces a plethora of indirect taxes with a single tax, and contributes to the ease of doing business. If corporate activity increases, so do tax collections, pulling down the deficit.

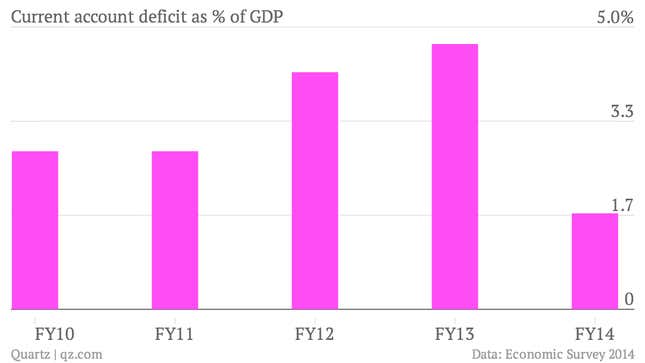

Current Account Deficit

This was another metric that had cramped the government’s choices in recent years, but it is now easing. Because it buys most of its oil from abroad, India’s imports always exceed its exports—and, thus, it runs up a trade deficit. It is sending out more dollars (to pay for imports) than it is receiving (from exports).

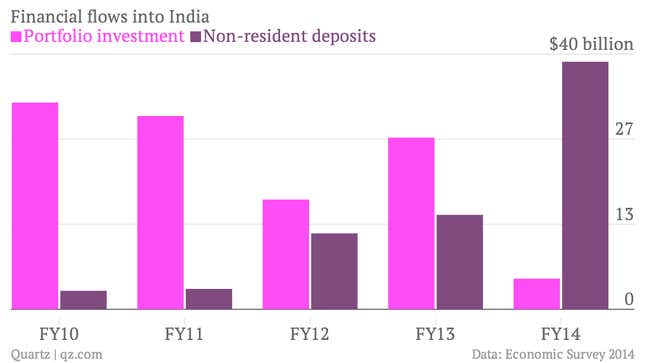

This currency shortfall is usually bridged by financial inflows into India like portfolio investments, foreign direct investment and remittances by Indians living abroad. But in bad years, when foreigners are reluctant to invest in India, this creates an imbalance. This is what happened in 2013-14, when portfolio inflows fell to $4.8 billion, as compared to $26.8 billion in 2012-13, as investors pulled their money out of India.

Fortunately, a combination of policy measures like a restriction on import of gold and higher inflow of non-resident deposits has since plugged the gap. This number is not precarious anymore, and Jaitley need not fret about it.

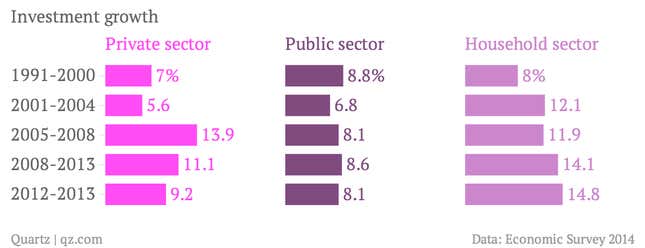

Private Investment Growth

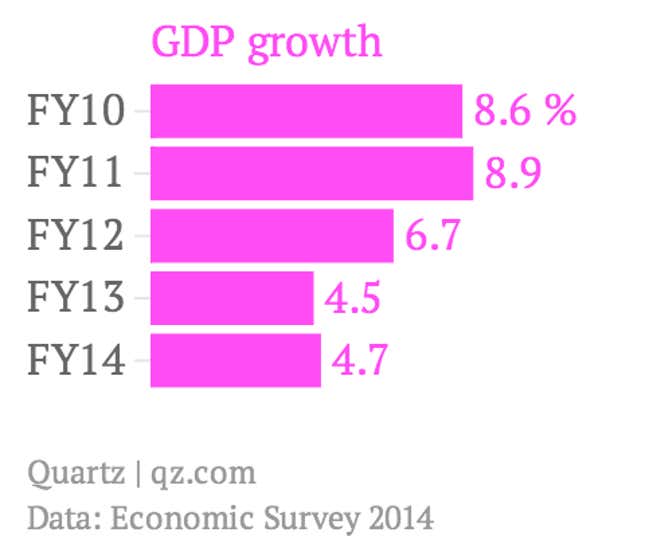

This is a common denominator between periods of strong growth and periods of weak growth. When the Indian economy surged to 9%-plus growth, between 2004-05 and 2007-08, increasing investments by private companies was a main driver, showing an expansion of almost two-and-a-half times over the previous preceding four years. Then, in 2012-13, private companies became reluctant to invest, and a slump ensued.

For GDP growth to return, revival of investment by companies is critical, and the finance minister will be looking to press levers to enable that. The Economic Survey, however, predicts middling GDP growth for this year—between 5.4% and 5.9%—and a return to the 7-8% range only from April 2016.

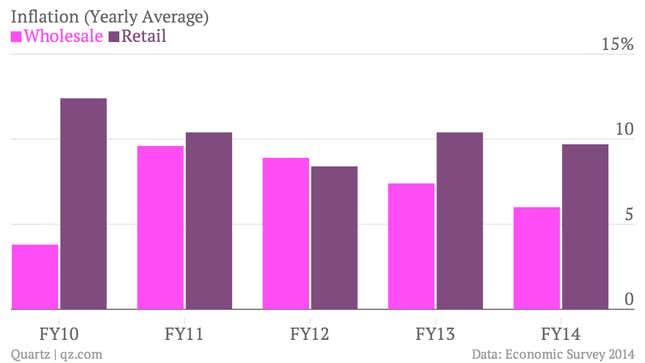

Inflation Rate

Rising prices of essentials have hurt the common Indian. It has also hurt the economy. Because of rising prices, India’s central bank has been tightfisted with money supply. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has continued to keep interest rates high, disincentivising companies from borrowing money for new projects—a must to resume the cycle of investment, higher growth and lower deficit.

The Economic Survey paints a mixed picture on the prices front. Although inflation as measured by prices at the wholesaler’s level has dropped and is now close to the RBI’s target of 5%, inflation as measured by prices at the consumer’s end is still close to 10%.

The Survey warns of prices staying under pressure because of two factors. One, the impact of the El Niño weather phenomenon on the Indian monsoons and, by extension, on agricultural production. Two, the impact of the strife in West Asia on oil prices. The RBI will watch the inflation number closely in order to move on interest rates. And Jaitley will watch the RBI while trying to do his bit on the price front.