The new budget is going to leave mutual fund and asset management companies fuming.

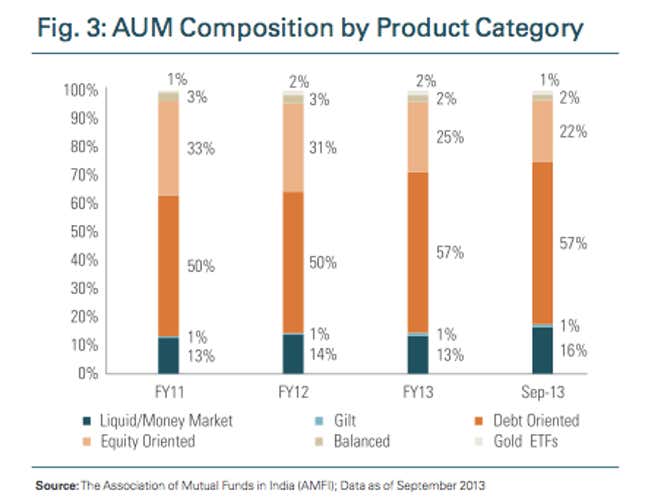

That’s because the majority of money in mutual funds is invested in debt-oriented schemes—short or long-term debt, issued by the government or by companies. These debt-focussed funds are a different asset class from equity funds, which invest in the stock markets, and hold nearly 60% of the assets under management in India’s mutual fund industry. The budget has effectively wiped out a tax loophole that makes these funds so attractive to investors.

The way things were

Previously, for all practical purposes, putting money in these funds was equivalent to a deposit with a bank, with the difference being that in a bank your return was known and agreed upon. The mutual fund’s return was based on the market, and you could even lose money.

But—and this is key—there was also a large tax arbitrage.

If you invest your money in a bank’s fixed deposit account for a year, the interest is recorded as part of your income and taxed accordingly. But with a debt fund, if you invest and exit a year later, you could end up paying almost no tax.

Because of a loophole in the tax laws, the gains on selling a debt fund, if it was held for a year, were considered a long term capital gain. As with all such gains, you could adjust for inflation. The income you made on the fund was only taxed at 20% of whatever was over and above inflation.

If you invested Rs100 in a debt fund, and sold it for Rs110 after a year of 8% inflation, your gain of Rs10 would be:

- Adjusted down to Rs2, since your investment of Rs100 automatically got inflation adjusted to Rs108, making the gains lower.

- Then you paid 20% of that Rs2 as tax, or 40 paise.

The returns from an equivalent fixed deposit investment that earned Rs10 would be counted as income, and the tax on that would range from Rs1 to Rs3, based on your tax bracket. A company would pay up to Rs3.3 in taxes. That meant a fixed deposit with a bank was no competition to a debt fund. Obviously anyone would choose to pay Rs0.40 in tax instead of Rs3. For companies, it was a no brainer—they could reduce their tax liability by 90%, from Rs3.3 down to 40 paise, for every Rs10 earned.

This arbitrage led companies to invest large sums in debt mutual funds in recent years. Debt funds have, as of June 2014, over Rs. 700,000 crore ($116.7 billion) under management. That’s 57% of the total mutual fund assets under management in India.

A good portion of this is from corporates, and the rest from high net worth retail investors.

Budget 2014 has taken this arbitrage away

Now, investors need to hold debt funds for three years to qualify for long term capital gains, instead of one. If you sell earlier, the gains are added to your income just like they are with fixed deposits.

Holding for three years is essentially too long term for most investors. If you get essentially the same returns with fixed deposits (which guarantee you won’t lose money) you might as well take a fixed deposit.

This changes the game. Mutual fund managers are likely to see their assets dwindle in favour of other investments, such as bank deposits, because their lack of a guaranteed return adds a layer of risk that was only justifiable because of preferential tax treatment.

Without the tax arbitrage, will debt funds continue to be attractive at all?

There are still advantages, of course. If you don’t withdraw money from a debt fund, you don’t pay any tax, no matter how much gain the fund has made. This helps if you don’t know for sure how long you need to stay invested. Fixed deposits, on the other hand, pay interest that is added to your income every year, even if you leave your money in the bank.

Additionally, fixed deposit interest has a withholding tax, while debt fund do not. What this means is that when you invest in a fixed deposit, 10% of your interest is withheld and paid to the government as tax. Debt funds do no such thing when you exit.

Still the lack of the tax arbitrage is a huge blow to debt fund managers.

Many companies might simply move to cash to fixed deposit accounts instead of keeping their money in a relatively risky debt fund. If debt fund assets fall by less than 20% or let’s say Rs100,000 crore ($16.67 billion), that would mean fund managers lose fees of more than Rs100 crore ($16 million), assuming fees are 0.1%.

For an industry that’s been hit hard by various regulatory changes recently, this is an added, substantive blow. While it can be justified as closing a loophole that was never acceptable in principle, it will have the unintended impact of hurting an industry that had just begun to attract large investors.

A number of fund houses may simply shutter debt fund growth, or merge schemes in order to stay profitable. Others might stop offering the large number of “367-day Fixed Maturity Plans” they created to fully leverage that tax arbitrage.

Investors in funds, though, will be hurt right away as the rule applies immediately. So, if you invested in a debt fund two years back, your tax treatment on an exit changed dramatically with Jaitley’s budget. Just hours after the budget was announced, investors were already taking to social media to complain.