Budget 2014 was keenly watched against a backdrop of change in India’s government and a change in ideology. Did that make its way into the new government’s economic approach? These six headline numbers trace how the budget moved from the previous United Progressive Alliance government to the new National Democratic Alliance government.

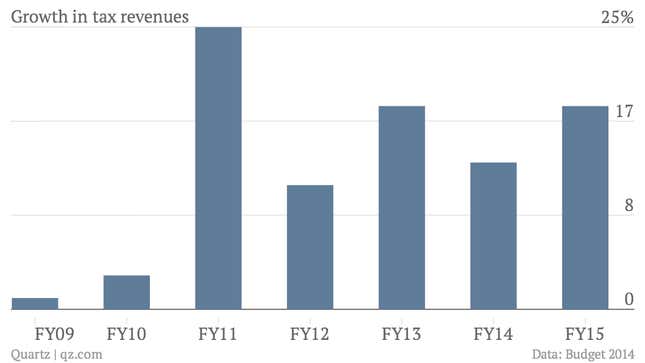

Economic ballast: tax collection growth

Why it matters: A proxy for how the government expects the economy to do in the coming year. The better the economy does, the higher the growth in tax collections.

UPA II approach: A mixed performance. In years when it was crucial to assess the health of the economy accurately, it misjudged. Notably, in financial year 2013-14, it projected tax collections to grow 19% at the beginning of the year. Around the end of that year, it revised it to a 5% fall. And the provisional data shows a drop of 2%.

NDA approach: Tax collection growth is assumed at 17% for 2014-15, which is higher than the GDP growth rate (at current prices) of 13.4%. Finance minister Arun Jaitley expects GDP growth to gradually perk up.

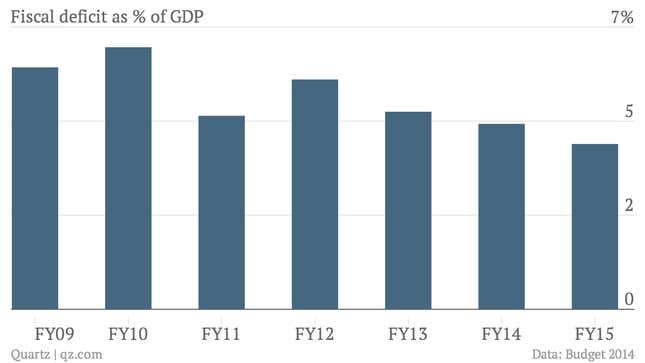

Path to growth: fiscal deficit

Why it matters: This indicates the government’s approach to lift economic growth: spend more or enforce fiscal discipline and rely on the private sector to start investing again.

UPA-II approach: A case of two halves. In the first two years, in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, it relied on additional government spending— amounting to about 2.5% of GDP—to stimulate demand. This extra cash in the economy is cited as one of the reasons for high inflation. In the last two years, though, it adhered to a path of fiscal discipline.

NDA approach: Has chosen fiscal prudence over pump priming the economy. Rather than government spending, Jaitley is leaning on private corporate investment. Thus, he has maintained the fiscal deficit target of 4.1% set by his predecessor, and is aiming to lower it to 3% by 2016-17.

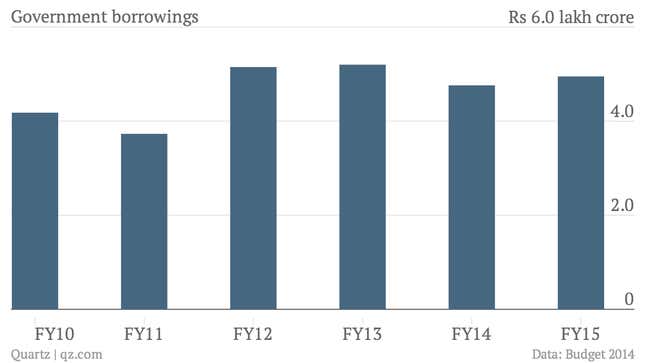

Hurdle to growth: government borrowings

Why it matters: In India, the government and the corporate sector compete for household savings—the main source of capital. If the government is borrowing heavily, it tends to crowd out the corporate sector. For example, in financial year 2012-13, household savings were estimated at 21.9% of GDP, but a great majority was invested in physical assets like gold and houses. Only 7.1% was available as financial savings, and the government was in the market for this, crowding out others who needed capital.

UPA-II approach: Although fiscal deficit fell from a high of 6.5% in 2009-10 to 4.5% in 2013-14, the absolute amount of government borrowings never came down. This, along with the fact that households were saving less in financial assets, put pressure on the availability of funds.

NDA approach: Jaitley has projected an increase in government borrowings. But he has also extended a spate of investment sops for households, which he hopes will channel their savings into the financial sector.

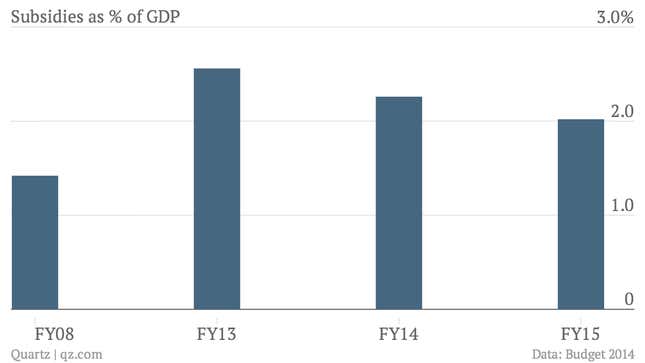

Culture of freebies: subsidies

Why it matters: The Indian government gives price discounts on oil, fertilizers and food. A lot of these benefits are badly structured and poorly targeted. In 2013-14, subsidies were estimated at Rs247,596 crore. In other words, the government gave away as freebies nearly a fourth of what it received as revenues. Pruning unproductive subsidies can free up funds.

UPA-II approach: Mostly, it backed a subsidy regime. However, towards the end of its tenure, its decision to increase diesel prices by a small amount each month is seen as a way out to eliminate oil subsidies.

NDA approach: Jaitley did not announce any specific measures to reduce subsidies. But he did announce the setting up of a Commission to “look into various aspects of expenditure reforms to be undertaken by the government”. He also proposed to overhaul the subsidy regime to improve its targeting.

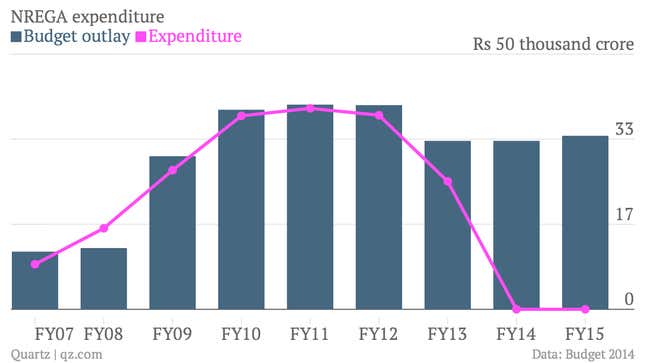

Poverty alleviation: social spending

Why it matters: That India, a poor country, needs social spending is not a point of contention. The debate is over the form it should take—government handouts or some form of market-based interventions. The focal point of this debate, today, is the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA), which promises 100 days of employment to a rural household in a year. About Rs250,000 crore has been spent on NREGA, but not all of it has reached beneficiaries and the quality of assets created is poor.

UPA-II approach: It adopted a rights-based regime. Thus, a citizen could demand certain rights—information, employment, education and food—from the state. NREGA was a prime example. Towards the end of its tenure, it passed a law that promised a subsistence amount of food to all households below a certain level.

NDA approach: Jaitley promised accountability for social spending, though he did not spell out the nature of the changes. The amount allocated to social spending, too, has stayed the same.

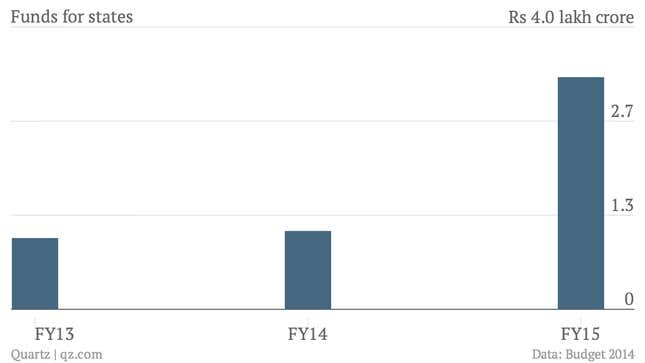

Decentralization: fund transfer to states

Why it matters: This essentially captures the engagement between the Centre, which gives the funds, and the states, which use those funds to implement programs. Usually, the funds would first go to the central ministry concerned, which would then channel it to the states.

UPA-II approach: The last UPA Budget took the radical step of sending the money directly to states. It reduced a layer in decision-making, but also reduced the clout of ministries. Funds transferred to states in the form of Central Assistance trebled.

NDA approach: Modi government did not tinker with that change.