What do you do when two of your business partners—among the biggest names on Wall Street—are sent to prison for their involvement in the largest insider trading fiasco in decades, leaving you to manage $1.4 billion of investments in South Asia?

“Well, I thought about two or three things,” said Parag Saxena, the CEO of New Silk Route, a venture capital fund that he co-founded with former McKinsey chief Rajat Gupta and billionaire hedge fund manager Raj Rajaratnam in 2006. (A fourth co-founder was Mark Schwartz, a Goldman Sachs veteran, who left the firm in 2008).

“One was I had a very important obligation to my limited partners (investors in the fund) not to leave them in the lurch,” Saxena said in an interview with Quartz.

Yet the crisis that New Silk Route and its team, helmed by Saxena, faced was dreadfully serious—and unrelenting.

About a year after the fund closed in late 2008, Rajaratnam was arrested for running an insider trading scheme surrounding his hedge fund, the Galleon Group; in 2011, he was sentenced to 11 years in prison.

Next, Gupta, then perhaps the most high-profile India-born executive in corporate America, was pulled into the maelstrom and accused of passing insider information to Rajaratnam. (In June, the former Goldman Sachs director began his two-year prison sentence.)

In 2012, as Gupta’s trial began, Saxena began assessing the situation. “I sat and thought about it and said, you know, should somebody else manage this portfolio?”

Educated at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay and Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, Saxena spent 23 years at INVESCO Private Capital, an investing firm where he worked on companies such as Costco, MetroPCS, Polycom, Staples, and Starbucks. And even as he left INVESCO to start another venture, Saxena’s dealmaking prowess earned him a place on the Forbes’ Midas list for best global investors in the tech and life sciences sector.

And by 2006, Saxena, Gupta and Rajaratnam were beginning to come together to work on New Silk Route, author and former Wall Street Journal journalist Anita Raghavan says in her 2013 book about the collapse of Galleon, The Billionaire’s Apprentice.

“But eventually it struck me that the people who were on the ground, people who were on the boards of companies had not changed. Because Rajat was not on any of the boards,” Saxena continues, “So, it made me think ok, what are the skill sets that I need replaced with Rajat gone—and that’s essentially where we added three very, very important and valuable people.”

New Silk Route brought in three executives designated senior operating advisors: former McKinsey Europe chief Herbert Henzler, former chairman of Visa International William Campbell and former treasurer of the International Finance Corporation Nina B. Shapiro. “I thought that the three of them could replace the skills that Rajat had given us,” added Saxena.

But New Silk Route had also lost something else that was equally valuable and markedly more difficult to replace, as Gupta and Rajaratnam fell from grace—goodwill.

“It can be lost in an instant, and it takes many years to be replaced,” admits Saxena, “And I’m hoping that once we actually have a few exits, we will fully regain that goodwill.”

The problem is that there really isn’t much to say about New Silk Route’s performance thus far, because the company has only partially exited one investment so far in India, according to Venture Intelligence, a venture capital and private equity research firm.

The exits are coming

The buoyant economic sentiment in India, following the election of a new government, is helping Saxena. Stock markets are up, sentiment is rising, and after having nearly half-a-billion mostly locked up in the subcontinent, New Silk Route is keen on making some money.

“We are inundated by offers from bankers,” Saxena said. “Within 9-12 months, we should definitely see some exits. And we should see that same rate—if you think about the companies, we’re not going to sell everything at one time—we should see that same rate over the next probably three years.”

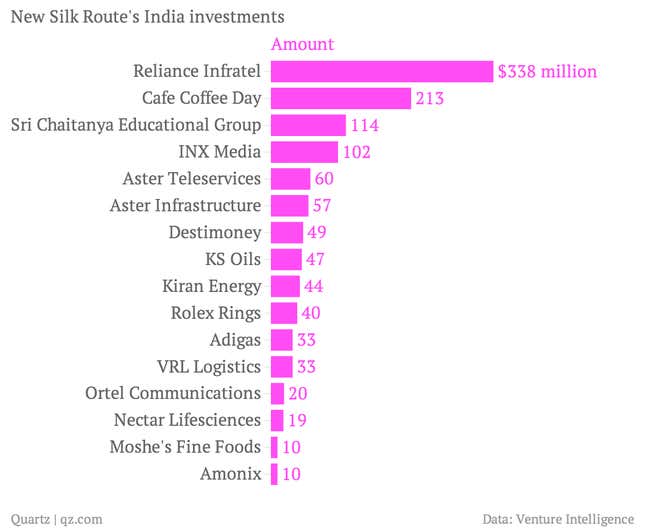

NSR’s portfolio in India is a mix of firms—ranging from telecom infrastructure companies to retail chain Cafe Coffee Day—and, according to Saxena, have a single underlying rationale: these are all businesses that feed off India’s rising GDP per capita.

“Some of these companies have grown ten-fold from the time that we originally invested,” said Saxena, adding that the companies where New Silk Route made its early investments will most likely be the ones it exits first, including possibly Cafe Coffee Day, where an IPO is said to be brewing.

Eventually, how the exits turn out will determine not only New Silk Route’s and Saxena’s legacy, but also his ability to float another South Asia-focused fund, which he seems keen on.

“Once we have a few exits out of the way, I think we will reassess the situation, look around and see whether we’ve rebuilt some goodwill,” said Saxena, “And whether that rebuilding enables us to raise another fund.”