Without BKS Iyengar there would be no yoga industrial complex, no streams of yoga acolytes spilling from the studios of Union Square in Manhattan and King’s Cross in London, no yoga taking Central Park, no yoga Groupons or yoga apps or free yoga downloads. What’s harder to understand about the inventor of modern yoga, the author of the so-called yoga Bible—the 1966 tome Light on Yoga—was his significance as a cosmic, present-meets-past-meets-future figure. From his humble roots as a poor, bootstrapper South Indian, Iyengar became one of the century’s great visionaries and, to his detractors, an eccentric with a touch of the megalomaniacal. He was inarguably the world’s most influential figure in yoga. But even more so, he was a millennial in the truest sense.

Iyengar was born in 1918 to an ultra-religious Brahmin family in a dusty Indian village outside Bangalore bearing the name of his clan, Bellur (the B of BKS—Bellur Sundara Krishnamachar). Geniuses and prodigies are born in the unlikeliest of settings, and Iyengar’s was that. He was poor, sickly, and badly educated—a terrible student of schools that taught by rote, a “backbencher,” he called himself in his autobiography. It was by fluke if not his glacial will that he found himself a student of yoga at the palace of the Maharaja of Mysore in 1936, thanks to the invitation of his uncle: another eccentric of his time, the proselytiser for yoga and Ayurveda, Tiruvanamalai Krishnamacharya. Iyengar quickly became his uncle’s top student.

Iyengar lived through momentous times and movements in India, and fashioned his yoga to keep pace with each. It is in this context that his legacy today is the most stunning. When he came up through the ranks at Krishnamcharya’s Mysore Palace Yoga Shala, yoga was not only an eccentricity but something fetishized and remote in India. Krishnamacharya and his students, dressed in traditional Brahmin facial markings and clothing, were self-consciously exotic, figures of a new era in India when the Independence movement was ascendant.

Images from the Mysore Palace school look, to today’s viewer, like notes from outer space. Krishnamacharya wears the traditional horseshoe-shaped forehead marking of the ‘U’ Srivaishnavite Brahmins of Tamil Nadu. Iyengar, from the “Y strain” of Srivaishnavites, wears the line marking. Both wear the sacred thread. The specificity of these markings speaks to centuries old and hyper-specific clan distinctions with little meaning to anyone outside that sub-clan. What is lost on that viewer is that such images looked just as alien to the people of that time.

A handful of medieval texts described asanas mastered by Iyengar and his fellow students at the school, but the bulk of the subject matter went only as far back as the eighteenth century and in many cases seemed to be made up. What was significant about the school’s mission was not its historicity in the least. To the contrary, it was the boldness of this yoga’s claim to be historically authentic. It was not, in the least. It was, rather, an attempt to glorify India’s past. That it was largely made up spoke to the right-place-right-time genius that Iyengar then rode spectacularly through the twentieth century.

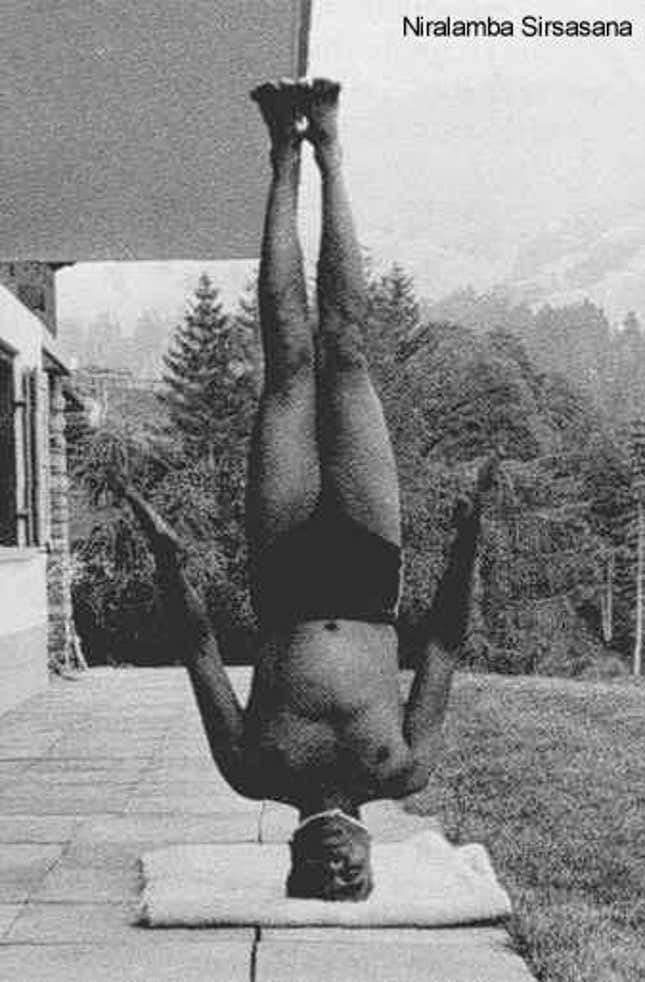

As times shifted in India, so did Iyengar. His yoga became a tool of the Independence movement, borrowed by the militant pro-independence underground up to partition in 1947. While his early yoga was tied to Hindu separatism, Iyengar allied himself with the secular Congress Party after its victory post-Independence. Iyengar’s Light On Yoga, often called “the Yoga Bible,” was written during the early Congress years before finally getting published in 1966. For a bible it is explicitly secular. Its spirituality is ecumenical. Its mentions of Hinduism are limited to yoga poses’ eponymous sages and abstruse discussion of Vedantic philosophy.

Later, when Hindu nationalism swept India in the 1990s and the Bharatiya Janata Party came to national power, Iyengar became newly religious. He seemed, then, to be a man of contradiction: a supporter of India’s attempt to build nuclear weapons; a believer in yoga as a martial sport in the training of soldiers and militants; and a supporter, perhaps most controversially, of India’s far right Hindu Nationalists and their questionable doings during the Ayodhya/Babri Masjid affair.

Over his life, BKS Iyengar had many detractors. He was criticized by Western students for being strident and physically brutal to the point of abuse. There was often petty infighting in the world of Indian yoga, and his critics—often from his same clan—accused him variously of self-promotion, opportunism, and, if hypocritically, of being egotistical, possessive of yoga’s name, boastful, and swellheaded. While as a human Iyengar could worry about the criticism to the point of self-destructiveness, it also made him stronger. He believed in yoga. He believed in its powers for healing. He grew older and softened, and after his first heart attack in 1997 in particular, came to believe in its powers to foment world peace.