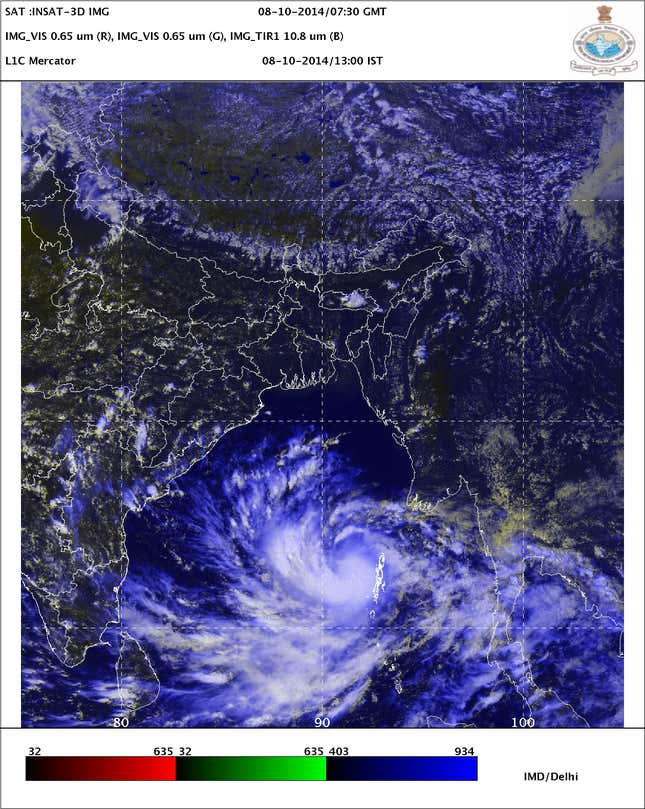

Paradip, Helen, Jal, Phailin and now Hudhud. The eastern coast of India has always been prone to deadly weather formations that develop over the Bay of Bengal, and this year is no different. On Wednesday, the Meteorological Department sent out an official alert that a depression over the Andaman Sea had intensified into a cyclone.

The storm has been named Hudhud, a reference to an Afro-Eurasian bird, in accordance with the proposed cyclone name list. The Met department expects it to have severe impact over north coastal Andhra Pradesh and the south Odisha coast over the next 36 hours. The official bulletin expects extremely heavy rainfall from the evening of October 11, followed by speeds of up to 150 km/h on 12th morning, as well as extremely rough seas.

Quite clearly, those living on the eastern coast are in for a rough end to the week.

But this is not India in 1999. Back then a super cyclone killed more than 15,000 people, mostly in Odisha, and ended up disrupting the lives of 20 million others. Last year, however, the casualty count for the most severe cyclone to hit India since 1999 was kept down to just 38 people.

So how did India manage to go from more than 15,000 deaths in 1999 to keeping the number of casualties to double digits?

Forecasting

Improvements in two areas have been key: weather forecasting and evacuation procedures. The most effective way to ensure extreme weather events do not cause tremendous destruction is to be warned about them early on and to move people out of the way.

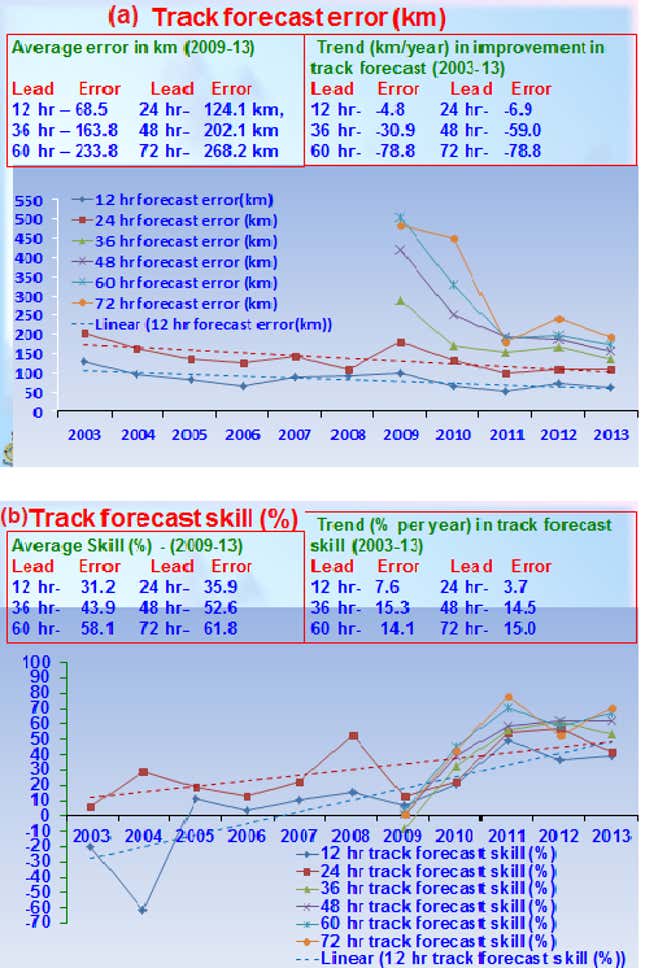

The Met department now tracks the difference between its forecasts and the path that the storm eventually takes. Using this forecast skill metric, Indian meteorologists have substantially improved their accuracy when it comes to predicting such weather events, making it easier for disaster management authorities to then take action.

The difference in the number of fatalities between Cyclone Phailin and the Uttarakhand cloudburst is instructive here. Both storms happened last year, yet Uttarakhand left more than 5,700 dead and millions affected. Although Phailin would also affect millions, its casualty count was kept to double digits. A big part of this was simply that there was no advance warning about the Uttarakhand cloudburst, while the Met department and local authorities had been tracking Phailin for weeks.

Evacuation

By the time there were four days until Phailin made landfall – almost exactly a year ago now – warnings had been spread through the affected zone, ensuring that 400,000 people had moved out of the most vulnerable zones. Eventually, more than 1.2 million people were evacuated, the largest such operation India carried out in more than two decades.

“Government cooperation, preparedness at the community level, early warning communication and lessons learned from Cyclone 05B [in 1999], contributed to the successful evacuation operation, effective preparation activities and impact mitigation,” stated a report filed by the United Nations Environment Programme’s Global Environment Alert Service. “This event exhibits the importance, benefits and effectiveness of the use of early warning for a massive disaster.”

According to UNEP, the government of Odisha spent more than $255 million over the last few years on cyclone mitigation projects. This included the building of evacuation shelters, conducting planning exercises, conducting drills and strengthening embankments.

“Successfully evacuating a million people is not a small task,” said a memo from the World Bank, which provided funding for some of Odisha’s disaster management projects. “This cannot be merely achieved by kicking the entire state machinery into top gear for 3-4 days following a cyclone warning. This has taken years of planning, construction of disaster risk mitigation infrastructure, setting up of evacuation protocols, identification of potential safe buildings to house communities and most importantly, working with communities and community-based local organisations.”

Hudhud

As of now, Hudhud does not appear to be turning into a Super Cyclone, although the Met department is expecting severe weather when it makes landfall this weekend. Teams from the disaster management force are prepared and expect to have a clearer idea within a day of where the storm is likely to hit land.

Authorities in Ganjam district, where it is expected to have the most severe impact, have ensured they have sufficient manpower to deal with any fallout. More than 300 evacuation centres have also been kept ready, although the government hasn’t asked any residents to leave their houses, because the area of landfall is yet to be properly forecast.

The cyclone has already had some effect in the state, with vegetable prices going up steeply and residents rushing to get essential commodities. But after the mostly positive experience of Phailin, the government seems confident about taking on Hudhud as well, with chief minister Naveen Patnaik insisting that the state has prepared all contingency plans and will now wait to see what IMD forecasts have in store.

This post first appeared in Scroll.in