In June last year, a small town in the heart of Britain wanted to hold a festival to commemorate the 75th anniversary of their most famous icon moving to town. Immediately some locals went up in arms insinuating that this author was a racist, sexist and classist, and also—the clincher—“not a very nice lady”.

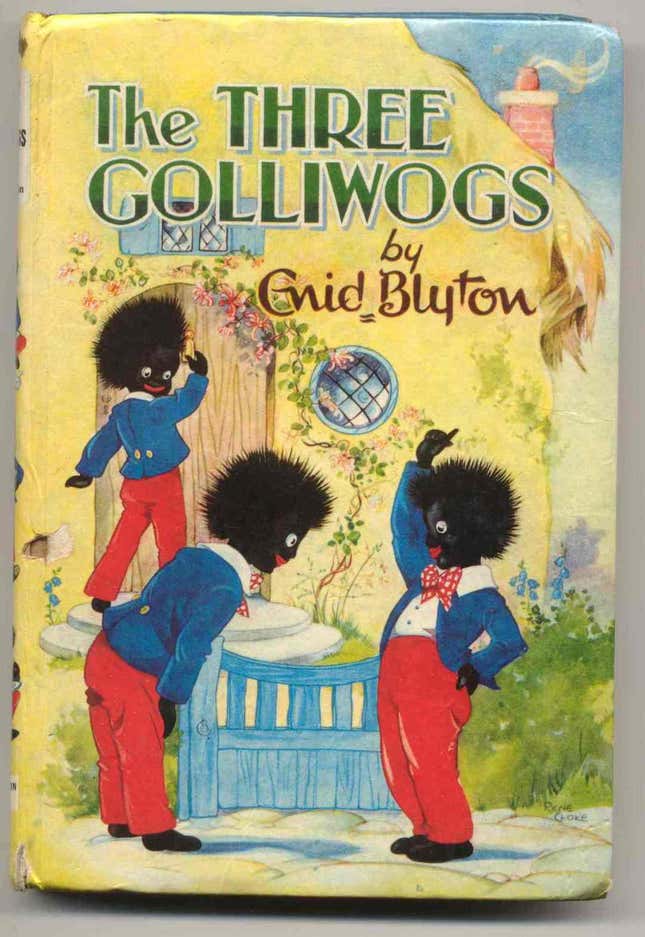

Enid Blyton’s books may have sold more than 600 million copies across the world but that hasn’t stopped them from being intermittently subjected to bans and ruthless revisions.

For years, Noddy books were banned because of their “racism.” Critics have pilloried the author for presenting “black toys” as villains, because in one book, a group of golliwogs asks for Noddy’s help in a forest, only to steal his car and clothes. Others have accused Blyton of being a classist: “Now that we have money, you can go to a real school!” exclaims George’s mother in the Famous Five. And sexism, they say, abounds: Famous Five’s ‘feminine’ Anne or The Adventure Series’ Lucy-Ann are forever laying out picnic mats and making beds while the boys are the first to intrepidly go through trapdoors.

However, if one examines the twenty-four Noddy books (as Professor David Rudd does), golliwogs are portrayed as antagonists only in this one instance—monkeys, goblins and teddy bears are up to no good far more often.

While there may be the odd reference to “having money,” they are few and far between—Blyton’s protagonists succeed by dint of their wit, hard work, good character and of course, magic. And for every one of George’s or Secret Seven’s Peter’s retorts about the superiority of boys, there are a score of strong girls like Darrell Rivers or the O’Sullivan Twins to look up to. One might dismiss this point by saying that there is no ‘superior’ boy for the reader to benchmark them against, but one need not then look any farther than the Naughtiest Girl becoming the monitor.

This is not to suggest that the racist, classist and sexist traces that do exist in Blyton’s books should be passed over completely. As one parent points out in her blog, these can be used as talking points with children (when they are old enough). Parents and teachers can discuss with their wards how they feel about Julian expecting Anne to lay the picnic mat because she is more of a “girl” than George or the Five Find Outers labelling swarthy gypsies as “suspicious.”

But to suggest that the books should be banned from the nursery and library altogether for their racism, classism and sexism is absurd. Perhaps political correctness needs some perspective. Like the books of Joseph Conrad, Aldous Huxley, or Agatha Christie, Enid Blyton’s are a product of their time and milieu, and should be recognized as such. Anecdotal research shows—and my personal experience echoes this—that children reading Enid Blyton do not notice the traces of xenophobia or elitism. They are far more engrossed in the midnight feasts and climactic denouncements.

Ah, but the critics continue, Enid Blyton was not a very nice lady. Obsessed by her career, she was often, as one of her daughters has said, cruel to her children. Others have accused her of divorcing her husband too summarily. To them, I would say two things: first, perhaps Blyton, too, was a product of her times—looked down upon for trying too hard to maintain a work-life balance, and second, should we then also stop reading Byron and Salinger and watching Allen and Polanski?

Enid Blyton’s enduring appeal lies in her ability to get children hooked to books. As author Michael Morpurgo says, “Her books were terrific page-turners in the way no others were. I had all sorts put into my hands when I was very little—I was offered Dickens at eight—that were not suitable for boys my age at all. But with Enid Blyton, I found I could actually get into the story, and finish it. They moved fast, almost as fast as comics, and there was satisfaction to be had on every single page.”

Blyton introduces a world of endless possibility to children across the world and across all ages. As one literary critic has remarked, “What hope has a band of desperate men against four children?”

In Blyton’s world, various permutations and combinations of children, dogs and monkeys tail suspicious men down winding village lanes or up treacherous mountains, recover hidden treasure and fading maps from decrepit castles, and catch perfidious smugglers in eerie lighthouses and farms. Suddenly, the adult who is forcing you to drink your milk or finish your homework becomes commonplace in the larger scheme of things. You have better things to do: a trapdoor to find, a code to decipher, an adventure to embark upon. Parental authority has no place here: adults, as a Mr. Goon or a Mrs. Kirrin know only too well, are either ruthlessly mocked or quite inconsequential.

She gently leads countless children into their first flights of fantasy. Go up a precarious ladder on a tree and who knows whether you will find yourself in the Land of Do-As-You-Please or the Land of Topsy Turvy? Sit on a chair in a shop, and suddenly you’re rescuing pixies from giants and attending magician’s parties. And as you’re walking down the street, you might encounter a fat gentleman with slightly pointy ears who will rescue you, imperceptibly, from your school bully.

But perhaps you started off as a precocious little realist:

“There was once upon a time a little girl who didn’t believe in fairies.

‘But Betty, there are fairies, because I’ve seen them,’ said her brother Bobby.

‘Pooh! You’re telling stories!’ answered Betty crossly. ‘There aren’t fairies, or gnomes, or elves, or anything like that, so you couldn’t have seen any.’”

Suddenly though, you’re whisked away to a strange land where nothing seems familiar, and in a Glittering Palace that you reached on a magic train, a Queen tells you:

“You’re a silly little girl. Because you can’t leave Fairyland now! No one is allowed to if she comes here and disbelieves.”

This, here, is your introduction to formidable rulers in Oz and Wonderland. To clapping for the fairies of Neverland. To hoping that the Sea of Stories will rejuvenate. To looking for horcruxes and teaming up with Hobbits. And before you know it, 6 o’clock Tales and 7 o’clock Tales, Fifteen Minute Tales and Twenty Minute Tales have shown you a life where the next page is the only place you want to get to.

This post originally appeared at The Scribbler.