India’s steel mills are scrambling to source one crucial commodity—iron ore.

Even as the country’s coal sector inches towards normalcy, with the central government adopting a new policy of auctioning coal blocks, India’s iron ore sector is still in the doldrums.

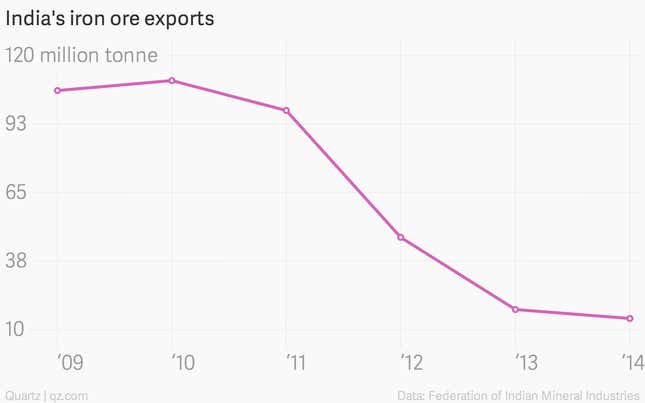

From one of the world’s biggest exporters of iron ore four years ago, India has now turned into a net importer of the mineral as it seeks to feed its steel plants.

Partly, this is a consequence of the Supreme Court’s ban on mining iron ore from four years ago, after the apex court moved to curb illegal mining. Other factors include uneven actions by a clutch of state governments as they dither in renewing mining leases that steelmakers badly need.

“We wish the central government had given as much importance to iron ore sector as coal sector,” Prasad Baji, an independent market analyst told Quartz.

And the result is that some of India’s largest steel companies are being forced to source ore from the international markets—some for the first time in over a century—while others are shelving expansion plans.

The ban backstory

In 2011, troubled by massive illegal mining and its environmental effects, the Supreme Court banned mining of iron ore in Karnataka, followed by a ban in Goa and Odisha.

Two years later, in 2013, the court allowed the resumption of iron ore mining in Karnataka, but with a cap of 30 million tonne per year. However, many mines in the state are still shut on the back of pending clearances.

In 2014, the Supreme Court lifted the ban on iron ore mining in Goa, although it imposed the issuance of fresh leases as a pre-condition. The court also capped iron ore mining in Goa at 20 million tonne per year. And in Odisa, in May this year, the court ordered closure of mines due to non-renewal of old leases.

Jharkhand government, too, closed 12 of its 17 iron ore producing mines as their leases had expired, hitting Tata Steel hard, but the Jharkhand High Court on Dec. 11 reportedly allowed Tata Steel to resume its operations.

Even though there have been some mine renewals in Goa, the second largest iron ore exporter in India, the state government wants to take it slow and decide only by March 2015 to clear the renewals. Odisha government, too, has decided not to renew any iron ore mines for now.

The cumulative impact of these decisions has been that imports have dramatically risen while exports have plummeted.

Steelmakers suffer

For India’s steel companies, it’s turned into a raw material crisis that will eventually impact balance sheets.

Tata Steel, ranked 11th largest steel producer in the world, has had to resort to importing iron ore for the first time in its century-long history. JSW Steel, with a capacity of 14.3 million tonne per year, is still waiting for its iron ore mine allotment after setting-up its plant in Bellary, Karnataka in the 1990s.

Moreover, JSW Steel has shelved its plans to build a 10 million tonne steel plant in the eastern state of West Bengal because of the delay in allocation of iron ore mines and coal mines.

“Looking at the current scenario, it does not look like mining will resume soon in Odisha and Jharkhand,” Dhruv Goel, managing partner at SteelMint, a steel research, analysis and consultancy company, told Reuters. “Imports are expected to hit 11-12 million tonnes this financial year.”

Reform please

“Even though the iron ore mining issues are state government specific, like in Karnataka, Goa, Odisha and Jharkhand, the central government can still do a lot as all mines are governed by the Mines and Minerals [Development and Regulation] Act,” Baji said.

The Narendra Modi government intends to amend the Mines and Minerals [Development and Regulation] Act—or simply, the MMDR Act—to include provisions that would allow bidding for mineral mines like iron ore and auctioning of the same.

“While the draft amendment to the act proposes auction for non-coal minerals, central government can revise other parts of the act to address the current issues, for instance, those related to second and subsequent deemed renewal,” Baji added. For a second or subsequent renewal of a lease, the state government typically only gives its approval if it feels the renewal is necessary for mineral development.

Till then, the fate of India’s iron ore sector—and that of its steelmakers—lies in the hands of individual state governments.

The only silver lining is perhaps that global iron ore prices have also bottomed out.