India’s rural doctors are endangering the lives of millions of young children with their sheer incompetence.

More than 90% of medical practitioners in rural India prescribed wrong—and potentially dangerous—treatments for cases of diarrhoea and pneumonia, according to a report published in the American Medical Association’s monthly journal, JAMA Pediatrics.

Those two diseases are responsible for every 318 out of 1,000 deaths of children under five years of age. In 2010, over 600,000 children died (pdf) because of pneumonia and diarrhoea in India, while an estimated 300,000 died in 2013.

For more than two months in 2012, researchers recorded the practice of diagnosis and treatment of diarrhoea and pneumonia in 11 different districts in Bihar, which has one of the highest child mortality rates in the country.

The study saw the participation of 340 local health care practitioners to determine the “know-do gap”—or the discrepancy between what practitioners know and what they actually practice—in India’s healthcare sector.

Though the study was restricted to Bihar, ”it is plausible that our findings are generalisable to rural India, where most healthcare is provided by untrained practitioners,” Manoj Mohanan, lead author and professor at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, told news website Indiaspend.

Shocking revelations

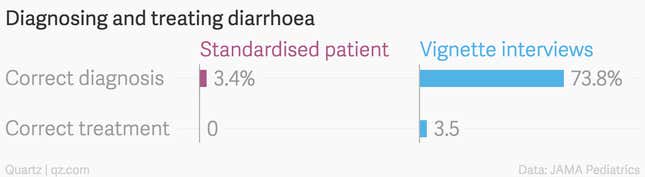

The data was collected by two means—vignette interviews and standardised patients. A vignette is a hypothetical case created to test a practitioner, while the standardised method is an actual case involving a real patient. In both cases, a practitioner’s performance was observed and recorded on the basis of the key diagnostic questions asked and the examinations conducted.

The “know-do gap” was substantial, for both trained and untrained practitioners, who failed to offer the correct diagnosis—or the correct treatment—to actual patients. In contrast, they performed slightly better in hypothetical situations.

For instance, in diarrhoea—where the only treatment necessary is oral rehydration salts (ORS) and zinc—merely 3.5% of practitioners prescribed affordable and accessible remedies in the vignette interviews. Instead, some 20.9% offered unnecessary antibiotics and 68.8% prescribed ORSs with other drugs that were not needed.

With standardised patients, no practitioner offered the correct treatment for diarrhoea, while over 70% prescribed unnecessary antibiotics.

For pneumonia, 59% practitioners made the correct diagnosis in vignettes, but only 8.8% prescribed the correct treatment. An additional 43.8% offered antibiotics.