Indians love to hoard gold. The World Gold Council estimates that 22,000 tonnes of gold are in private hands across the country—$1 trillion (Rs.62.6 lakh crore) stashed away in cupboards, safes and temple vaults, collectively worth over half the size of the Indian economy.

And every year, about $40 billion (Rs.2.5 lakh crore) worth of gold is bought and sold in the country. So, jewelry ads interrupt nearly every primetime television program; jewelry stores line the commercial districts of every city; and Dhanteras, the pre-Diwali festival for which business communities traditionally buy gold, has become a nationwide event.

Idle no more

Gold is a national obsession in India, and that’s because it is widely seen as a safe investment in an uncertain economy.

“Gold is primarily a hedge against inflation and currency fluctuation,” Abhay Aima, group head of equities and private banking at HDFC told Quartz. “There is a fascination for physical gold which extends deep, deep down into the Indian psyche, especially among the middle class.”

But most of that gold has been sitting pretty in homes and lockers instead of circulating through the economy—until now.

In his budget speech on Feb. 28, finance minister Arun Jaitley announced two provisions that could dramatically change the world’s largest gold market: incentives for people to keep their gold in banks, which could then be lent to gold vendors; and a sovereign gold bond that would convert gold from a physical asset to a financial one.

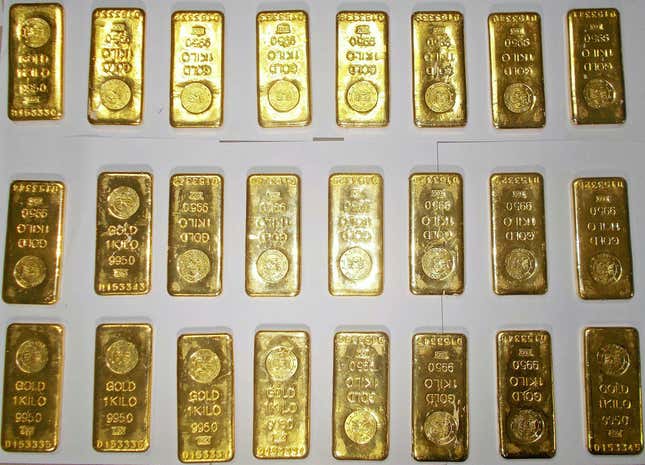

There is so much idle gold in India that even recycling a small fraction of it could potentially help cut down the trade deficit and fund other investments in the economy. The deposit program, dubbed the “gold monetization scheme” by Jaitley, would likely accept only gold bullion, or the solid gold bars and coins that account for about a quarter of total gold stocks. (Jewelry, which makes up the rest, can’t be lent out so easily.)

Just 10% of this bullion, estimates the State Bank of India, could raise over Rs1 lakh crore in gold deposits over the next three years. And because Indian banks are required to maintain about a fifth of their deposits in gold or cash reserves, more gold in their vaults could free up money to lend for housing or business.

“This is a very good scheme,” said Samraj Jain, whose family runs the M. Shermal Jain Jewellers chain in Hyderabad. “Instead of their gold lying dead, people can give it to the bank and earn some money.”

“The banks can then lend it to jewelers at a higher interest rate,” he explained. “The depositor is happy because his gold is safe, the jeweler is happy because he doesn’t have to import so much gold, and the government is happy because gold is being recycled.”

Like online shopping

Indians have traditionally viewed gold as the ultimate risk-free investment, a tangible assurance against economic chaos. But that too may be slowly changing as a younger generation shifts to more productive investments like bonds.

“Maybe the fascination for gold won’t go away, but holding it in a dematerialized form becomes more acceptable,” said Aima, pointing to what he calls a growing class of “post-liberalization” investors. “Why hire a safe in a bank, when you could just hold a bond? It’s the same logic as online shopping—you no longer need to touch and feel what you’re buying.”

The budget provisions come as the government grapples with the current account deficit from gold imports, which, at 800 to 1000 tonnes annually, are the second largest Indian imports after oil.

In 2013, in an attempt to stem the surge of imports, the government hiked gold duty to a record 10%. But gold traders say the high tariff, which is still in place, has only encouraged the black market. Last week, customs officials at the Mumbai airport said their hauls of smuggled gold surged 300% in 2014. Still the 856 kilograms they confiscated is only a drop in the bucket: the World Gold Council estimates that 175 tonnes of gold were smuggled into the country last year. Gold prices saw their sharpest drop in over a year on Friday as strong American jobs data nudged investors towards riskier assets.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of the budget proposals will come down to the details. An earlier gold deposit scheme launched in 1999 failed, for instance, over tax concerns and excessive minimum deposit requirements. There are also logistical questions of how to ensure that the gold being deposited is pure, and how to transfer it to vendors. But many economists and industry insiders are optimistic.

“The government has to think this through. Any gold deposit taken from the public needs to be returned in gold,” SK Ghosh, the chief economic adviser to the State Bank of India, told Quartz. “At the end of the day, the idea is that the gold that was outside the system is brought to the bank. This is a huge opportunity.”

You can follow Vivekananda on Twitter at @vnemana. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.