India is drastically losing land in the Sundarbans—a cluster of 54 islands in West Bengal—to climate change.

Recent satellite analysis by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) shows that in the last ten years, 3.7% of the mangrove and other forests in the Sundarbans have disappeared, along with 9,990 hectares of landmass, due to erosion.

The Sundarbans—a vast mangrove delta shared between India’s West Bengal and Bangladesh—is an immensely fragile ecosystem. One of the biggest threats, as it has turned out, is sea-level rise driven by climate change.

As the small islands on the fringe of the Sundarbans shift, shrink and disappear, left behind is a trail of climate refugees.

No land, no people

Tuhin Ghosh of the School of Oceanographic Studies at Jadavpur University has been studying changes to the tiny islands that dot the mouth of the Hooghly river. In a study published last year, Ghosh and his co-researchers found that between 1975 and 1990, islands like the Lohachara and Bedford disappeared from their original locations.

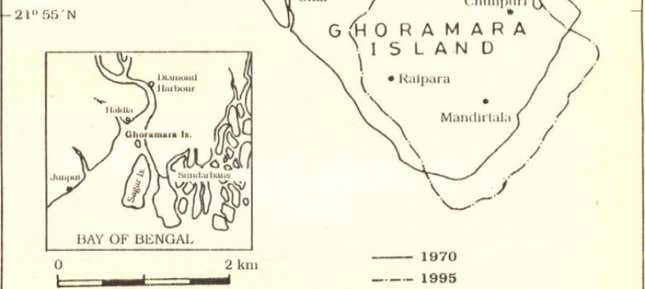

Another small landmass, Ghoramara island, however, is the most striking example of vanishing land and displaced people. Satellite images show that in 1975, Ghoramara had a total area of 8.51 square kilometre that shrunk to almost half—or just 4.43 sq km in 2012.

“Everywhere there is sharp cutting of the river banks; chunks of mainland are being displaced from the mainland and getting submerged,” Ghosh said.

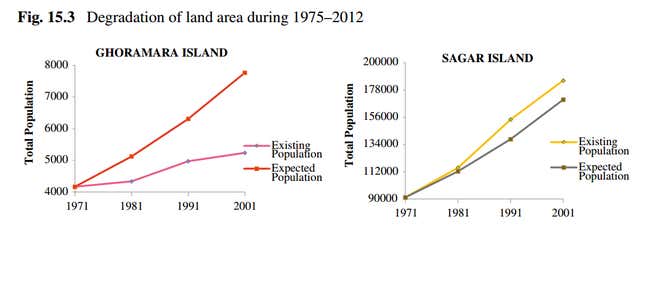

With thousands being pushed off the islands, the population growth dropped to 0.55% per year, while the overall growth of the administrative block in which it is located is about 2.1%.

The neighbouring Sagar Island took in the refugees from the vanishing islands, including at least five Ghoramara villages. Its population growth, as a result, outpaced the expected trend between 1981 and 1991.

The exact number of displaced people from Ghoramara is unknown, largely because there are no actual government records. However, people estimate that some 4,000 people have already left.

The residents—faced with disappearing lands and livelihoods—rest their faith in the local Gods. There are no official policies yet for adapting to these changes.

Ghoramara and its neighbouring submerged islands are about 20 kilometres up the river. The loss of their landmass is not driven just by rising sea levels—the most drastic effects of which would have been seen lower downstream. Instead, the engineering interventions to revive Haldia port in the eighties, and the resulting water diversion may be at play in the region, said Ghosh.

“There may be some effects of sea-level rise, but there is more of an impact from the change of the river hydrodynamic condition created by the guidewall,” Ghosh said.

A case was filed in the National Green Tribunal (NGT) about human interventions in the Sundarbans, including illegal construction of buildings and infrastructure. The ISRO study, showing a loss of almost 10,000 hectares of land in the past decade, came out of the NGT’s order for a satellite analysis to determine violations.

“There is unauthorised construction. And there are illegal encroachments of brick kilns and shrimp farming,” said Subhash Datta, amicus curiae (an impartial adviser to the court) in the case. “If we can’t arrest these things, then the pressure on the land will become even more adverse.”

This post first appeared on Scroll.in.