As a kid growing up in India, I remember asking why I got bitten by mosquitoes more than others. To calm down my irritation, I was told that my “blood is sweeter than others.”

That may sound silly, but it’s not completely off-the-mark. Turns out, some people do get bitten more than others, and there are a number of factors that turn them into mosquito magnets. The carbon dioxide exhaled and the body heat emitted are what first attract mosquitoes, but then as they get closer it is the unique smell of a body that ensures the prickly bite.

Past studies have shown that mosquitoes prefer beer-drinkers, pregnant women and people with blood-type O (which I happen to be). These preferences are the result of body odour and there could be as many as 400 chemicals on your body, albeit in very small quantities, which could be playing the role to attract or repel mosquitoes.

Now, in a new study published in the journal PLOS One, researchers from the UK and the US find that your genes probably matter even more.

It’s those genes, again

The study involved 18 identical and 19 fraternal twins from the TwinsUK cohort, between the ages of 50 and 90. Because identical twins have identical genes and fraternal twins only share half their genes, an experiment involving both can be used to differentiate between how nature and nurture affect different outcomes. All things equal, if identical twins show similar preferences as compared to fraternal twins, then statistical analysis can reveal how much genes affected those preferences.

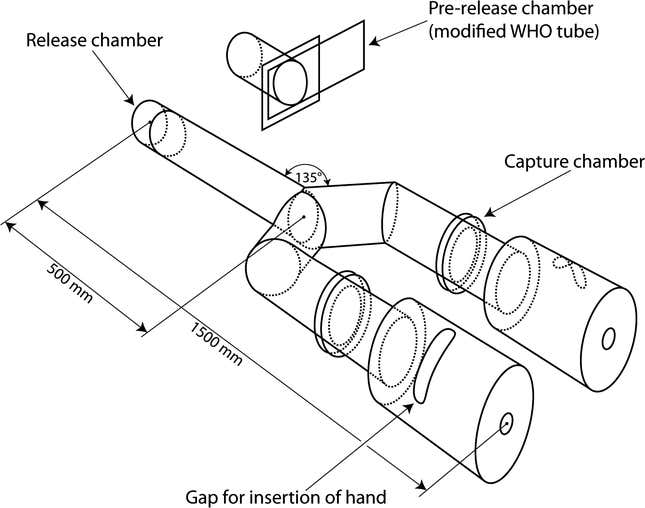

To be doubly sure, for 24 hours before the experiment, the participants were asked to avoid alcohol or any strong-smelling foods, such as garlic, onions or chilli. The brave twins were then asked to put their hands into a special box containing 20 female mosquitoes. (Among mosquitoes, it is only the females who do the biting, because they are the ones hoping to find extra nutrition to lay eggs.)

The box was such that mosquitoes could smell the hands, but they were prevented from biting the volunteer. Each participant was then given an attractiveness score, based on who attracted more mosquitoes.

Identical twins, the researchers found, had more similar attractiveness scores compared to fraternal twins. This showed the presence of a genetic component to mosquito attraction. Statistical analysis revealed that about 67% of the differences between mosquitoes’ attraction to people can be explained by genes alone.

The researchers acknowledge that the sample size of the study is small to draw a robust conclusion. However, the heritability of this trait is similar to that of height or IQ, so the conclusions might hold for a larger study.

The similar preferences for identical twins probably occur because genes also have influence on the odour people produce. These odours are produced not just by bodily excretions, but also the bacteria that live in and on our bodies. And even our bodily bacteria, known as the microbiome, are influenced by our genes.

The peak mosquito season has begun in the Northern hemisphere. If you happen to be in the wrong parts of Asia, Africa and North America and are unlucky enough to have those genes and that bodily smell, what can you do? Nothing much apart from using mosquito repellant in copious quantities.

This post was also published in Lokmat Times. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.