In early August, the Indian prime minister addressed anxious questions in parliament regarding the impact of the recent downturn in the Chinese market.

Indian exports, he confirmed, had declined precipitously to a third of last year’s figures, and imports too were down by more than 30%. As the New York Times reported, the prime minister agreed that “Indian traders were being put to considerable harassment by Chinese authorities and that Peiping was violating the terms of the accord.”

That’s right, ‘Peiping’: this was in August 1959, after all.

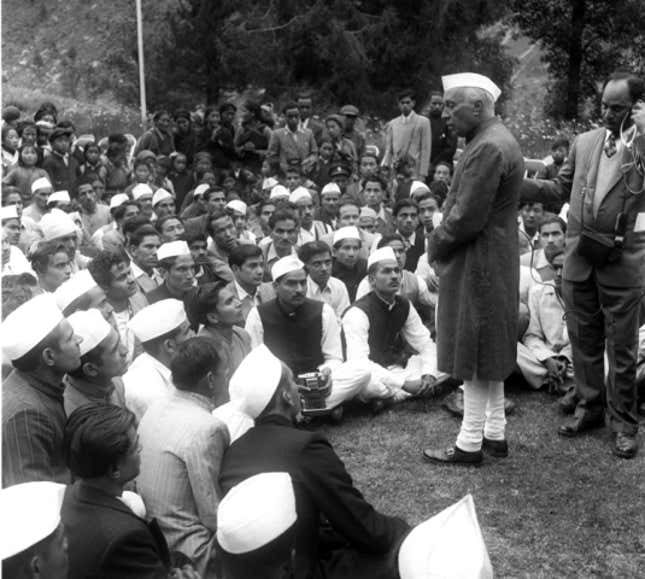

The commerce Jawaharlal Nehru was referring to was the overland trade with Tibet, worth some $525,000 in 1958. It comprised mostly of Tibetan wool and a wide range of Indian manufactured goods from cloth and cigarettes to dismantled trucks and jeeps for the Chinese army, hauled over the Himalayan passes between Lhasa and the Indian town of Kalimpong, popularly known as the “Harbour of Tibet.”

Come August 2015, Beijing’s economic policies are headline news in New Delhi again in the wake of the devaluation of the yuan and the precipitous fall in Chinese stocks, which triggered an alarming 6% crash in India’s own BSE Sensex and a two-year low in the value of the rupee.

To be sure, the effects of China’s “Black Monday” have been felt not just in India—but across the globe. And other than the fact that the events of both August 1959 and August 2015 diminished many Indian fortunes, they express such different realities that they might as well have occurred on different planets.

Perhaps they have. The world is indeed a very different place today. China is now India’s largest trading partner, the value of bilateral trade is estimated at over $70 billion and India’s trade deficit is around $48 billion. Indian imports are now dominated by consumer goods, notably mobile phones, while exports to China are led by iron ore and more recently cotton.

And yet, despite the significant scale of this trade and the glaring fact that that the two countries’ fortunes and misfortunes are inextricably intertwined in a global economy, it was not long before an element of schadenfreude emerged in Indian comment and analysis of “the Great Fall of China.” One senior member of the Bharatiya Janata Party, Subramanian Swamy, welcomed the crisis as an “opportunity for India,” noting that he had predicted the collapse of the Chinese economy by 2020. “I’m glad that it is happening five years earlier,” he said. Similarly, a webchat with readers hosted by an editor of a leading Indian financial paper was peppered with queries along the lines of “will India surge ahead of China?”

I asked Rahul Jacob, managing editor of the Business Standard and host of that discussion, what he made of such sentiments. “The ‘rivalry’ felt by Indians but not at all by Chinese is a figment of our imagination,” he said. “It’s all of a piece with the heady optimism that characterised India between 2003 and 2008. In economic terms, nothing could be further from the truth. India is a $2 trillion economy and China a $10 trillion behemoth.” Indian sentiments were misled, he argued, by the “many misguided journalists who write China-India books— whereas no Chinese has written one yet— believing that India is always on the cusp of finding its rightful place among the league of great nations.”

The latest financial fibrillations have certainly reminded Indian market analysts of the precipice of 2008. Yet, despite Jacob’s argument, the combination of Indian hubris and Chinese hauteur, he suggests, has marked relations between the two nations for a much longer time.

It is in fact a pattern that stretches back to their earliest engagement as neighbours, following China’s occupation of Tibet and its apparition on India’s borders in the 1950s. By the time Nehru made his dismal announcement on the decline of cross-border trade the die had been cast: Chinese paranoia over Indian support for Tibetan rebellion and India’s intransigence in dictating the contours of the border would soon lead the nations to the brief but defining war of October-November 1962. The campaign was marked, famously by China’s emphatic victory, followed by an enigmatic withdrawal. But its most unequivocal outcome was that India and China ceased to be neighbours.

Trade relations between the countries were re-established in 1978 and grew modestly at first, until the early 2000s when figures crossed the billion-dollar register. But no commerce of any significance would ever reappear along the 4,000 km land frontier— now the world’s longest disputed border—that divides them.

Last year I visited Kalimpong, that sometime Harbour of Tibet. Perhaps I was motivated by a misguided ambition to write an India-China book. I discovered a fallen place, marked forever by its 1950s heyday with tall, crumbling Bauhaus warehouses and shuttered cinema halls clustered around a main street called Main Street, while once-opulent company guesthouses slumped defeatedly on the wooded slopes above.

I strolled through fetid lanes and heard tales of a town of bordellos and casinos, of opium dens and fine Chinese restaurants, and the magnates and aristocrats, Tibetan, Chinese, Nepali and Marwari merchant dynasties who once ran the town. I could almost picture it. I did see the overgrown ruin of the former Chinese Trade Mission and the still charming Himalayan Hotel where Heinrich Harrer once stayed.

Before I got to Kalimpong I had located one of the last living Indian merchants who had made and lost his fortune in the China trade. He was now a prosperous hotelier in Gangtok. “I was also seven years in Tibet,” said Moti Lal Lakhotia, a bright-eyed and vigorous man in his eighties. “We had branches in Kalimpong and Yatung and Phari and Gyantse. I sold a lot of bicycles there—and some Willys jeeps and Dodge trucks.” And then he lost everything of course. But Lakhotia was not a bitter man. A few years ago he had even returned to Tibet for a holiday, flying from Kathmandu to Lhasa since there are no flights from India.

He had enjoyed surprising people by speaking Tibetan, he said. And no, he had no grouse with the Chinese. He had recently learnt that the People’s Bank of China was now honouring the accounts of Indian traders who had shut shop in Tibet when the war broke out. “They are paying back the money with interest,” he purred. “Chinese banks are very good.” The old man had only one lament. “Kalimpong is finished,” he said. “If only they would open the border…”

I travelled on towards the 14,000 foot Nathula pass and witnessed what now counts as border trade. A serpentine metalled road slid over the snowy crest of the pass through two ornamental arches, one Chinese and one Indian. A small traffic jam of perhaps 50 mini vans was parked on either side waiting for their respective permits to travel to the “International Trade Marts” a few kilometres away.

It seemed at first glance a picture of progress from the vintage photographs I had seen of mule trains and porters hauling bales of wool and tyres over the mountain. But the opposite is true: the old trade was a vibrant and expanding enterprise, pushing the existing infrastructure to its limits in a relentless effort to serve and expand markets.

The current trade is a parodic “confidence building measure,” hampered by strict quotas and an archaic list of “permitted items” such as yak tails. The annual value of this trade stands at about $2 million. On what was and could be the highway to Lhasa, this is driving with the brakes on.

The turbulent markets of August 2015 are indeed a reminder that crisis is also an opportunity. Perhaps it is too much to hope that India and China might recognise that for all their economic “rivalry” they really might as well be neighbours. If they did, the border would be a good place to start. “Only connect” as it were.

Standing on the crest of Nathula, even my homesick mobile phone seemed to want it. I only saw the message later. “Welcome to China,” it said.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at ideas[email protected].