As a white man, you can’t walk very far in India with a camera before you hear, “Aye angrez! Meri photo khench!” (Hey foreigner! Take my photo!)

Sometimes, they point to a friend and tell you with a giggle, “Take his picture,” but what they mean is, “Take my picture”. If you turn towards the catcaller, he will quickly collar an innocent bystander and pull him close in a tight pose.

Sometimes a person will stop right in front of you and smile, but refuse to let you pass. They don’t need to say anything. The message is made clear by eyebrows that dance in the direction of the camera. Many times, they will engage you in a chat about where you come from and what you’re doing in India. They will talk about anything—just passing time. But it’s obvious what they want: a portrait.

Until recently, I found these requests distracting. From time to time, if the person had an especially compelling face or was particularly insistent, I’d oblige. But mostly I’d pretend I hadn’t heard, or simply smile and wave back. My main reason for hesitating hitherto had been the knowledge that I would be unlikely to fulfill the accompanying request to send them a copy of their “footo”. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve returned from India with my pockets filled with scraps of paper on which are scrawled names and addresses of people whose portraits I’ve taken and promised to forward a copy.

I let the pieces of paper accumulate, telling myself I’ll get around to posting the copies soon. But soon I’d feel guilty in the knowledge that I’d never remember which address went with which photo. Still, I dared not toss them away. Weeks after I’d left India, the scraps lingered in my wallet or fell onto crumpled reams of credit card receipts, boarding pass stubs and bus tickets. They became dim and torn. Eventually, I tossed them away.

And I would feel bad as if I’d betrayed trust. Those damn scraps of paper were diluting my enjoyment of making pictures in India.

There was another reason for my resistance to the friendly catcalls. Film. Every photographer knows that the more frames you shoot, the better the chances of producing a good image. And to shoot a lot of frames requires a lot of film, and a fair amount of money.

After investing in a couple of camera bodies and the best possible lenses I could afford, I protected each roll of transparency film like a child. With only 36 shots per roll and usually no more than three or four extra rolls in the bag, each shot counted. Sorry, I’d whisper to myself like some character from the TV show Seinfeld, your face just isn’t “frame-worthy”. I was the ugly foreigner.

Thankfully, digital cameras have changed everything. No longer does one need to ration every frame of every roll of film. The counting doesn’t stop at 36. It goes on and on—up to 4, 8 and 32 gigabytes. You can capture on one small digital card more pictures than you could with 30 rolls of film. Carry a couple of backups and you’re looking at 3,600 frames or more before you stop for your first cup of chai.

And the second request for a copy is usually forgotten in the joy and surprise of seeing their image pop up instantaneously on the screen. They laugh. They call friends around to have a look and for most, that immediate glimpse is sufficient.

Some years ago, after nearly 20 years, I made a trip to Allahabad, where I had spent much my youth. As I wandered through the bazaars of the city, I was at once pestered by catcalls, whistles and shouts of “Hey gora, take my picture!”

Again, I pretended I hadn’t heard. Thankfully, though, the idiocy of holding that position in the digital age knocked me upside the head. In an instant, I turned down a radical new path. I resolved to respond positively to every catcall, whistle and hectoring request for a portrait regardless of whether the subject was classically photogenic.

I decided the time had come to amend for my past betrayals and meanness. Whoever wanted to have a portrait made, would get one. No ifs. No ands. No buts.

What began as a tactic very quickly developed into a strategy. Taking portraits on demand became a major personal project. While I’d earlier try to melt into a scene and not draw attention to myself or my cameras, I now tried to engage and encourage anyone who looked in my direction. If I heard someone yell out, I’d turn and walk over to them and begin clicking.

As a photographer, I’ve always been drawn to people and portraits. But nurtured on those iconic images exemplified by the work of National Geographic, I used long lenses and searched for dramatic faces. Or at least people doing “interesting things” such as washing clothes, praying, gesticulating. The portraits I selected represented a thin slice of the thousands I’d made. The majority were relegated to plastic sleeves and boxes to collect dust in the back of a closet—dismissed and labelled “not interesting”.

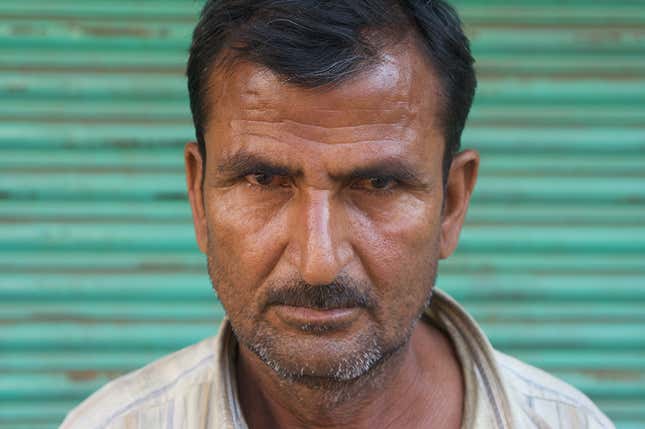

With my new project, however, I began to pay attention to the person behind the face. I understood that each and every face is unique. And full of quotidian drama. Because I was no longer doing facial triage and every face was considered frame-worthy, I was forced to see something more than the “iconic” in the portrait (or, to put it differently. I started to understand the meaning of icon in a new way).

I recalled the words of some sage that “every face is a reflection of God” and as such, absolutely worthy of being captured and admired. No longer was it just the funny, handsome, pathetic, terrifying or sad faces that counted, but each one of them. I started to glimpse the beauty of the aam aadmi.

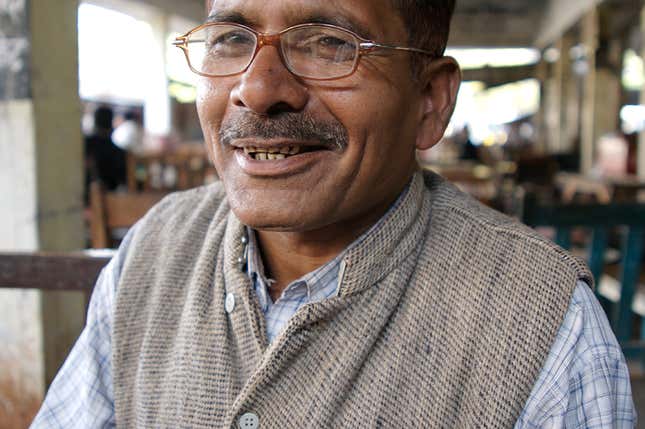

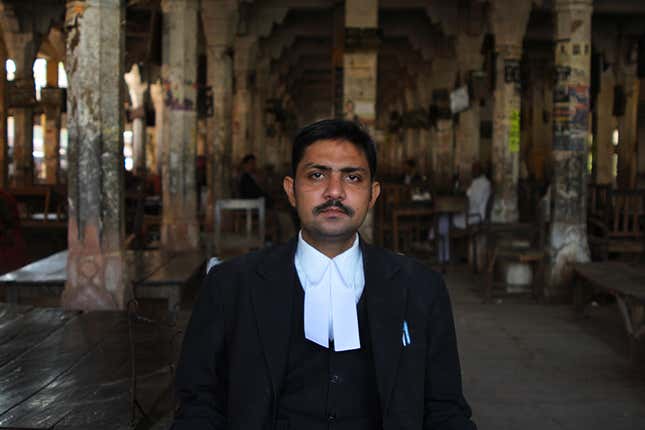

In these portraits of unknown, absolutely ordinary Indians, the focus is entirely upon them. They have not had time to dress up or prepare. They have simply asked to be photographed and have opened themselves up to the camera, warts and all.

The red tikka on their foreheads, the starched newly tailored shirt, the bandage on the forearm, unshaved faces, and the way they stand in relation to others in the group, all hint at an individual yet universal humanity. Unlike the photographed celebrity who represents an ideal, these people present reality. And to me, that is the more powerful and compelling argument.

I relish that these people had no time to prepare themselves. From catcall to photo, usually no more than a minute, often less, elapsed. What you see is who they are. The honesty and vulnerability inherent in these portraits is what makes this project so important to me.

Most of these portraits began with a whistle, or even a cheeky insult in Hindi. I don’t think they really expected me to respond.

When I came forward and indicated I was happy to take their picture, they often were taken aback. But only for the shortest time. Not quite believing I was pointing the camera at them, they would pose (or not) and earnestly thank me. Often they would fire off a bit more information which they thought important for me to know.

I’m always fascinated by what they choose to tell me. “I’m a bania,” a man told me, slightly embarrassed and yet proud of his station. “This is my Ferrari,” an autorickshaw driver told me as he moved in front of it. A couple of advocates in Allahabad began telling me why they thought the caste system was irrelevant to justice in India. “I’ve only got one wife,” a shopkeeper told me.

I never posed the subjects and portrayed them wherever they chose to stand, sit or lay. The process was over quickly, just a few minutes. If they were interested, we’d chat for a while and then part ways.

Like my guru, Raghubir Singh, who discovered in the automotivally ordinary Hindustan Ambassador a new photographic “way into India”, my own lifelong fascination with photographing India had been revived by “portraits on demand”.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].