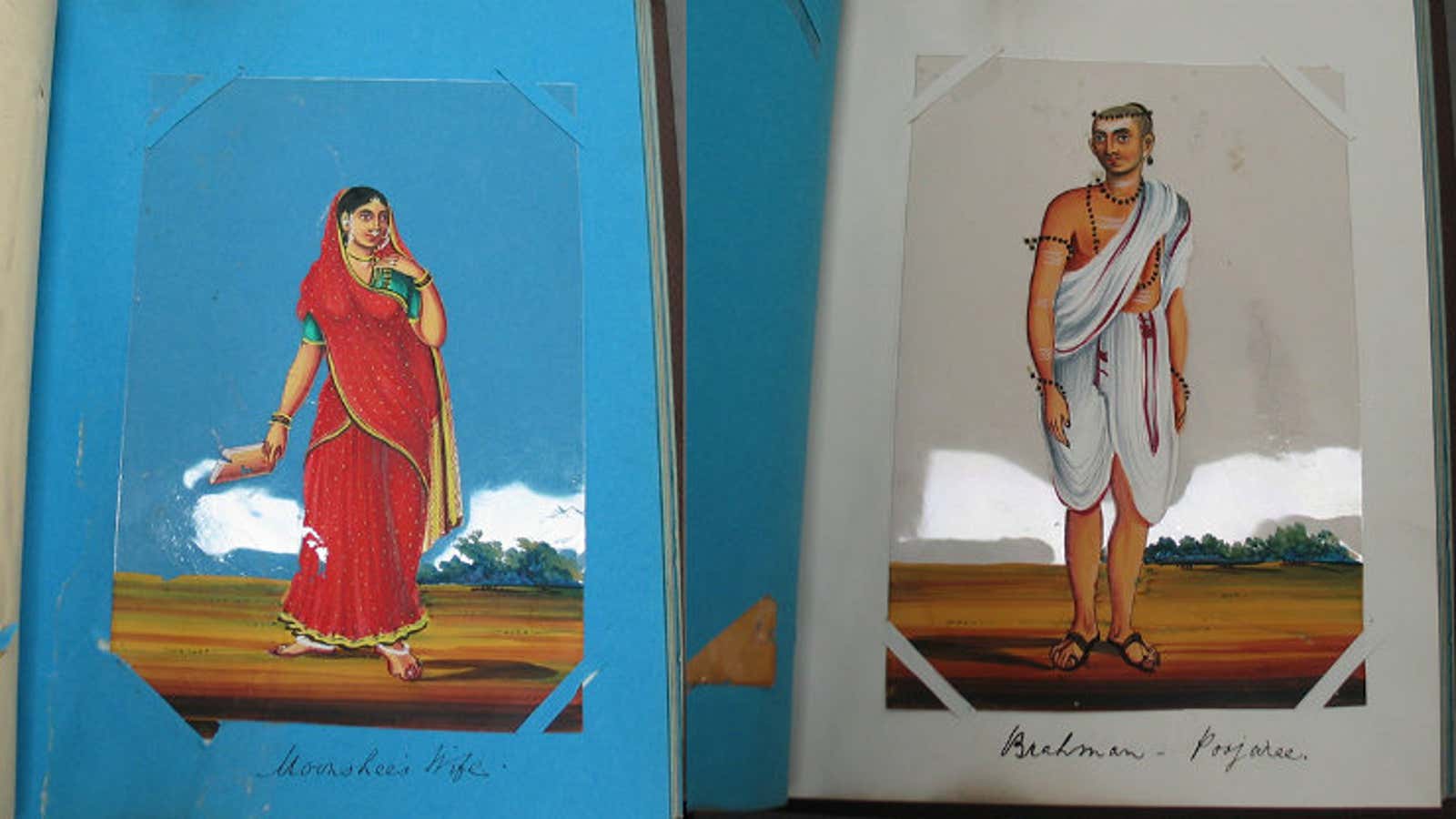

A woman peeks from the curtain of a wagon, rich men parade on a bejewelled elephant and a pensive scholar clutches the tools of his trade: these paintings, no bigger than playing cards, adorn transparent sheets of mica and were bought in India as souvenirs by sailor Charles Augustus Whitehouse in 1842.

They were painted in India for the colonial tourist trade and are so rare and fragile that Dr Kevin Greenbank, archivist at the Centre of South Asian Studies, admits “I get the shakes when I handle these.”

“They represent an important period in Indian art—the Company School of painting—when Indian art developed perspective,” he adds. Some depict courtly scenes, while others appear to be sets of costumed characters or Indian pastimes and trades.

The collection has 69 mica paintings. Their vibrant images are remarkably intact despite the fragility of mica—a transparent mineral—which may have been used by the painters in order to imitate the European trend for painting on glass. There are also six paintings on pipal leaves.

Today, they are held in the archives of the Centre for South Asian Studies, which houses a unique collection of letters, diaries, photographs and films belonging to ordinary British people who documented their lives in India and South Asia.

“What I especially like about the mica paintings is they accompany a pair of diaries written by a sailor who bought them when he stopped in India on his way from Liverpool to India on the Brig Medina.”

Unlike many diaries that have become a source of historical information, Whitehouse’s are a deeply personal and highly idiosyncratic account—so much so that they were often written as if there was no-one else on board.

Entitled The Sea-Pie, the diaries are inscribed to his mother, and come with a caveat scrawled across the front “Here it comes something hot from the oven. Mind your eye or it may burn your fingers.”

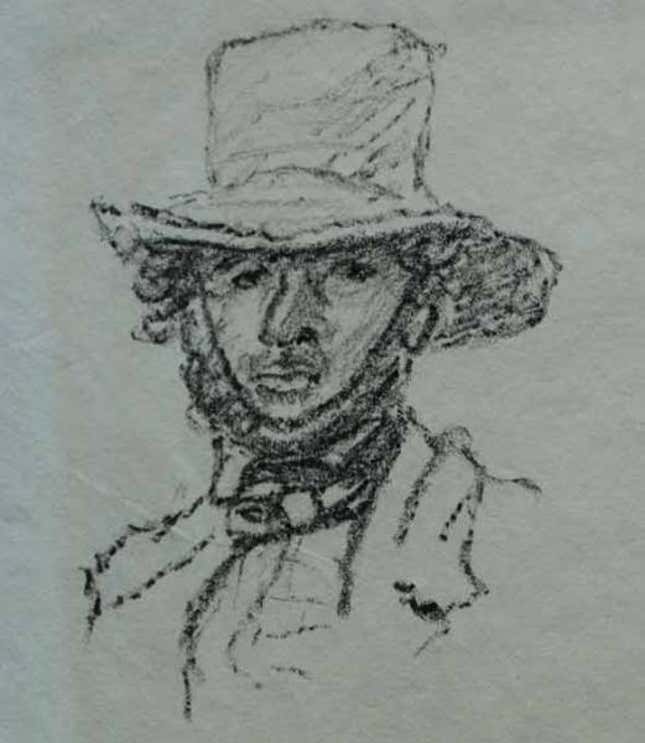

Alongside his self-portrait, seascapes, a map of his route and a smattering of voyage details —“Potato cakes for tea”—Whitehouse begins to dwell on his lost sweetheart back home, stolen away, he says, by another man: “Hanging, drawing and quartering would be really too good for such an intruder.”

As the Brig continues to be becalmed, the pages fill with plaintive poetry “Love in a woman neer sinketh deep, Into the bosom she lets him creep… Love in a man is a far different thing, Forms more than roses it doth then bring.”

Eventually, many pages later, the sad sailor rallies, bringing his melancholic meanderings to an end with: “So I’ve blued and blued and bored and bored you until I work myself back into my usual good humour. Apres les pluit, les bonne temps. The storm is over and I feel much refreshed… after moping for a good half an hour I went below for a cigar.”

This post first appeared on the University of Cambridge website.