Bollywood screenwriting is fundamentally bi- or multilingual, and English has long been part of the mix. Think of the dignified screen doctor of yesteryear, marked as an educated man by his occasional words in English. Now think: COOL! as in “Cool cool, style ka ye usool” (Cool is the rule for style), a refrain from a song in Roadside Romeo (2008)…

Cool is a word, cool is a value. Bindaas, in its original meaning perhaps the nearest equivalent Hindi word, has made it to the Oxford English Dictionary, but cool is somehow cooler.

FM radio hosts coolly whip between Hindi and English, with the advantage, at least in vocabulary, going to English, the tongue that defines upward mobility and which, accompanied by the right accent, will bring respect and a good job…

With boundaries between languages fluid and quickly evolving, it is often hard to say at exactly what point a word switches status from “English word used in Hindi” to “Hindi word of English origin.” English or new Hindi?

A few words have particularly caught my attention.

Life

English words can be heard side by side with their Hindi-Urdu Hindustani counterparts in Jab We Met (2007), written and directed by Imtiaz Ali and winner of the Filmfare award for Best Dialogue… Sirf hansi, khel, mazaaq nahin hoti hai zindagi, Geet. Life mein serious bhi hona padta hai. (Life is not only for laughing and having a good time; you have to be serious about life too.) This use of “zindagi” and “life” in one sentence may mean: I’m young, I’m modern, I’m metro, I’m on the go, but I’ve still got some poetry—in Hindustani—left in me…

Life is a term usually reserved for practical everyday matters; it is also ours to control. In Shyam Benegal’s Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008), generations clash in their visions of life. First, we meet Vindhya’s mother (Ila Arun) who wants to follow an astrologer’s advice and marry her daughter to a dog. We then meet the motorcycle-riding, fast-talking Vindhya (Divya Dutta), who has no intention of following that plan. “Hamaara life kauno life nahin hai ka?” (Isn’t my life a life?) she asks.

Time

According to the referential Platts’ Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi, and English, ‘vaqt’ simply means time. In film dialogue the distinction between zindagi (life) and vaqt can be blurred, at least when it includes the notion of qismat. In Muqaddar Ka Sikandar, directed by Prakash Mehra, with dialogues by Kader Khan, young Sikandar, the future Amitabh Bachchan character, is treated cruelly by almost everyone he meets. At one point he tells a bullying adult: “Aaj mera vaqt kharaab hai; vaqt ne mujhe maara hai. Isliye tu bhi mujhe maar le.” (My time is bad. Time has beaten me. So you beat me too…

In sharp contrast, Taxi No. 9 2 11 (2006), directed by Milan Luthria, with dialogues by Rajat Arora, uses the English term ‘time’, not vaqt, for that much-prized and limited commodity our watches remind us is ticking away. Ye Bombay hai; yahaan time ka matlab hai paisa. (This is Bombay; time means money here.) Time is about movement; it is not a state… In Jab We Met the nuanced distinction between time and vaqt becomes clear when the two words are used in quick succession… “Ticket kharidne ka time nahin mila hoga…inke saath haadsa hua hai. Bura vaqt hai.” (He didn’t have time to buy a ticket. He had a mishap. It’s a bad time for him.)

What Is This Thing Called Love?

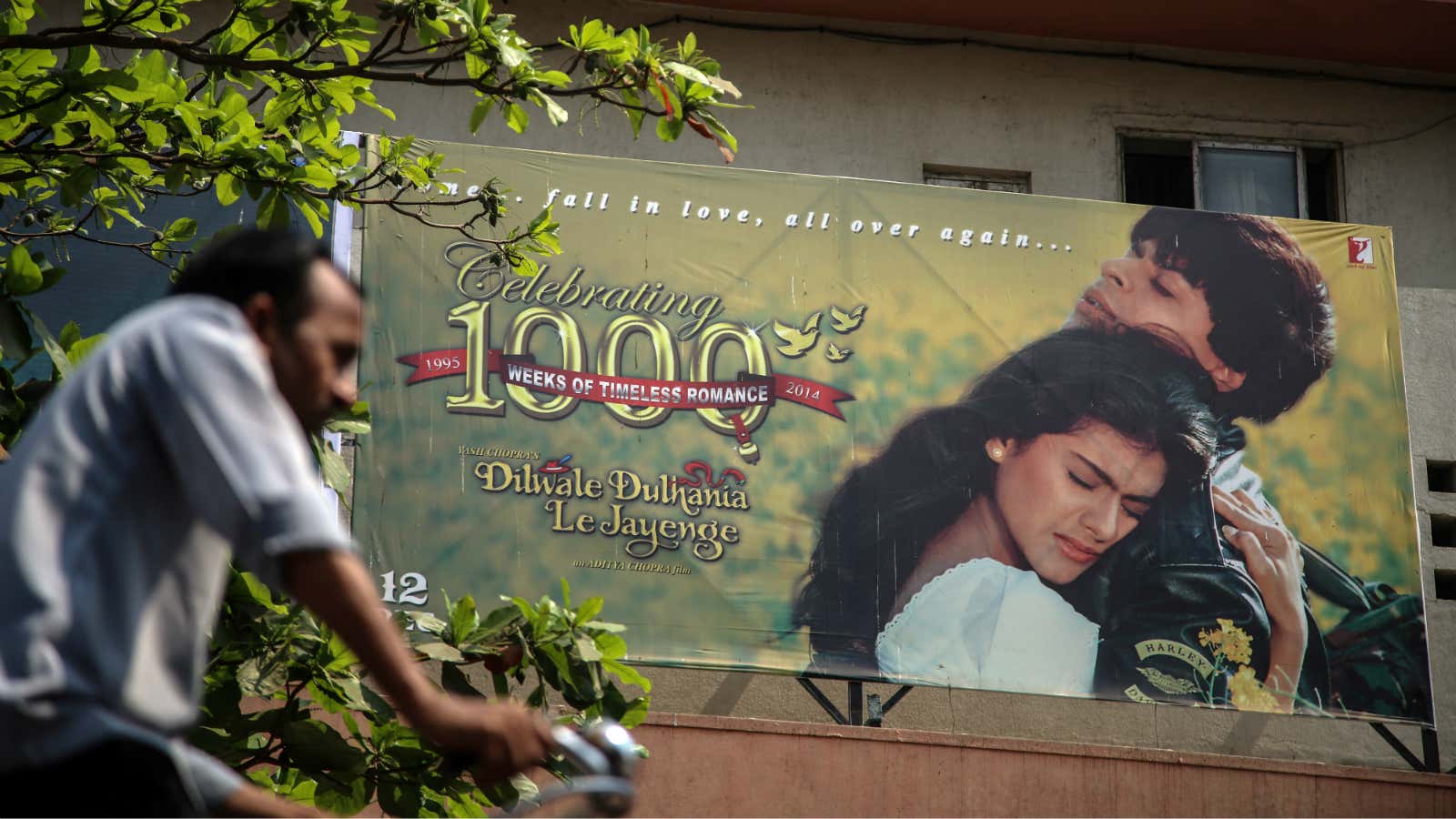

The term ‘love’ in Hindi cinema is not new. True, we didn’t hear it in the 1950s… But in Aradhana (1969) by Shakti Samanta, dialogue by Ramesh Pant, the Rajesh Khanna character says: “I love you. Tum meri ho” (You are mine)…

Pyaar, prem, ishq, mohabbat, with such a wealth of Hindustani vocabulary, why would one add love? One answer could be the self-consciousness that accompanies intimate feelings. Another language, beyond the passions and reflexes associated with one’s mother tongue (or “grandmother tongue”), can offer a kind of protective curtain to hide behind, the linguistic equivalent, say, of Nargis, playing the new bride in Mother India, with covered head and coyly downcast eyes…

The imported word “love” can offer a cover for the bashful; it can seem modern and exciting; for some, it can be culturally alienating, part of the metro India consumerist package one is urged to “buy”. The world view that English conveys can collide with more rooted linguistic and mental patterns of thought. Love, as it moves more deeply into Indian languages and culture, is problematic on several levels. How does one say “falling in love” in Hindi…and its corollary, “falling out of love”?

Guilt

The American-returned character played by Nagesh Kukunoor in his 1998 film Hyderabad Blues protests to his Telugu-speaking father, “Don’t guilt-trip me, Dad.” Many English words heard in Hindi cinema add nuance or a modern flavour. Usually, they have close equivalents in Hindi-Urdu. Guilt does not. I asked several people in the film industry for the Hindi translation of guilt. Most were stumped. One answer was pachhtaava. Yet this translates back into English better as remorse or regret. Jaideep Sahni concurred with several others that pachhtaava was the word for guilt. “But,” he noted, “nobody feels guilty.”

Perhaps then, in some form, karz (debt) would translate as ‘guilt’, though it would probably not find its way into film dialogue today.

Shit

…One generation’s most highly charged words might be the next generation’s informal but acceptable vocabulary… In the US, the seven words you can’t say on television refer to sexuality or excretion. One of the seven is ‘shit’. Though banned from public airways in the US and the UK, the same word has become part of youthful spoken English in metro India. Reflecting the trend, even ‘nice girls’ like Geet in Jab We Met freely use the word. She does not and would not, of course, use an equivalently strong word in Hindi-Urdu… And almost no one does.

Excerpted with permission from Rupa Publications India from the book Show Me Your Words by Connie Haham. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.