A senior leader of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has questioned the competency of the man who rightly predicted the global economic crisis of 2008.

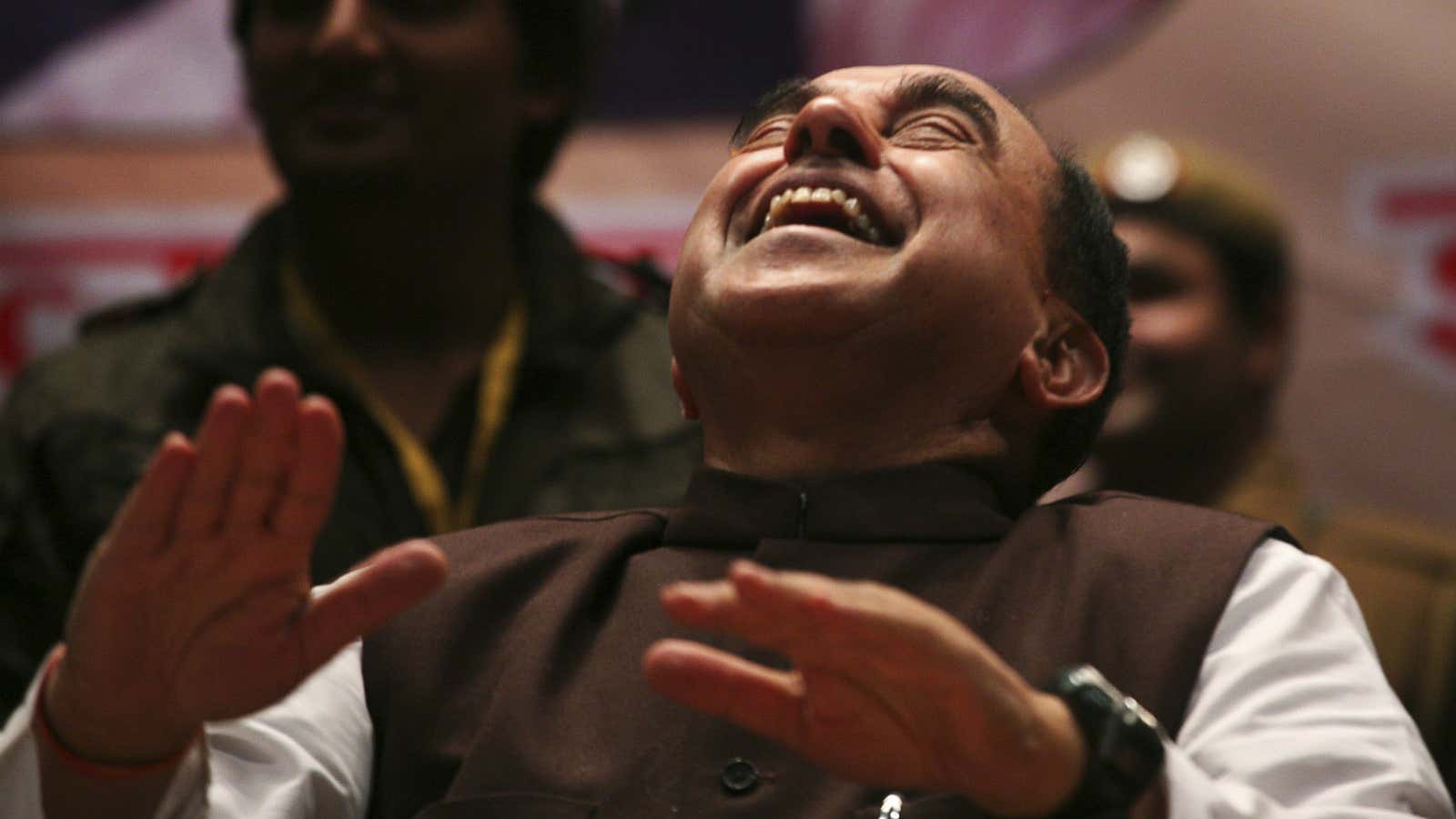

On May 12, Subramanian Swamy—the BJP’s enfant terrible—declared that Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Raghuram Rajan should be sent back to Chicago since he is unfit to be a central banker. Rajan’s three-year term is set to end this September.

Rajan is currently on leave from the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, where he’s a professor of finance.

There has been some friction between Rajan and the Narendra Modi government in the last few months, but Swamy’s rationale for such bold remarks is pretty bizarre. Here’s what Swamy said:

In my opinion, RBI governor is not appropriate for the country. I don’t want to speak much about him. He has hiked interest rates in the garb of controlling inflation that has damaged the country…(his actions) led to collapse of industry and rise of unemployment in the economy…The sooner he is sent back to Chicago, the better it would be.

Before jumping the gun, Swamy, once a visiting professor at Harvard University, should’ve have paid more attention to economics. Here’s why:

“He has hiked interest rates in the garb of controlling inflation. That has damaged the country”

Yes, Rajan did hike key interest rates in the country soon after he took control in August 2013. But it was more of a necessity than a choice. Retail inflation in Asia’s third-largest economy was high, at about 9.52% then. A rate cut or hike is the most common tool available for policy makers to contain inflation.

When prices of food and commodities are high, increasing the money supply in the economy pumps up demand, thus driving inflation upwards. Rate cuts in such scenarios mean letting more money into the system. An increase in interest rates, on the other hand, restricts money supply, pulling down demand. This, in turn, brings down inflation.

Sure, lower rates are one way to boost economic activity, but consumers are typically concerned with inflation, and managing growth and inflation is often tricky. And Rajan made it clear that his main objective was to bring down inflation.

“What is equally worrisome is that inflation at the retail level, measured by the CPI, has been high for a number of years, entrenching inflation expectations at elevated levels and eroding consumer and business confidence,” he said in Sept. 2013, during his maiden monetary policy announcement. He raised the repo rate 25 basis points to 7.50% on that day.

Since then, he has hiked the repo rate only twice. For most of 2014, he held rates, until inflation was under control and dropped below 6%. In March 2015, Rajan signed a formal agreement with the government to set an inflation target. The RBI will be held accountable in case it fails to stick to the targets set: within 6% by Jan. 2016, and within 4% for the following years. In April, retail inflation was at 5.39%. Now the repo rate is at 6.5%, the lowest in five years.

“(His actions) led to the collapse of industry and rise of unemployment in the economy”

Rajan took charge when the global economy was in the middle of the worst financial crisis since 1991. Major economies around the world were slowing, and India wasn’t an exception.

The Indian economy grew at just 4.4% in the June quarter of 2012-13, the slowest in four years. Since then, unlike Swamy’s claims of an industrial collapse, India’s GDP growth has improved to over 7%. This is partly also because the method to calculate economic output was changed in January 2015.

Besides, Swamy’s boss, prime minister Narendra Modi, has reiterated that all is well with the economy. Government data shows that foreign direct investment (FDI) is at a multi-year high and over 2.75 lakh jobs have been created under Modi.

To say then that Rajan’s policies led to a rise in unemployment is doubting the government’s credentials, if anything.

Banker of the year

Meanwhile, Rajan has often stood out among his peers.

The Banker magazine named him Central Banker of 2016, lauding his efforts to stimulate growth.

“Under Rajan, the management of monetary policy has been extremely effective, not only in terms of the use of the policy rate tools, notably the repo rate and reverse repo rate, but also through skilful management of liquidity in the financial system through tools such as open market operations and the use of the cash reserve ratio,” said Rajiv Biswas, Asia-Pacific chief economist, IHS Global, a consultancy.

Charan Singh, the RBI chair professor of economics at the Indian Institute of Management-Bangalore, said that “inflation targeting” has been Rajan’s biggest achievement. “He (Rajan) has certainly been able to anchor inflationary expectations. Despite all criticisms, he persisted and prevailed to ensure that inflation rate is down,” Singh said in an email.

“The monetary policy is a tight-rope walk and there are many parameters that need to be taken into consideration. Interest rate is one, but developments in the external sector also have a role to play in exports. Similarly, supply side factors, el Nino, climate change in terms of floods and hailstorms, droughts, hoarding, etc, all have a role in price setting. On regulation and supervision of banking, he has been transparent,” Singh added.

Whether Rajan will get a second term or not is the government’s call, but Swamy needs to check his facts again.