When Amazon announced in 2016 an additional $3 billion investment in India, it made clear its intention to dominate the Indian market and pose a massive challenge for India’s homegrown e-commerce companies, among which Snapdeal could be hurt the most.

The Gurgaon-based firm lags Flipkart on most metrics, and currently has Amazon India (Amazon.in) nipping at its heels for the second position in an overcrowded market.

Launched in 2010 by Wharton graduate Kunal Bahl and IIT-Delhi alumnus Rohit Bansal, Snapdeal has around 300,000 sellers and delivers in over 6,000 cities and towns in India. In March 2016, its gross merchandise value (GMV, or the total worth of merchandise sold through a marketplace) stood at around $4 billion.

The company is backed by Japan’s SoftBank, the Alibaba Group, Taiwan’s Foxconn Technology Group, American e-commerce firm eBay and Tata Sons chairman emeritus Ratan Tata, besides venture capital and private equity investors such as BlackRock, Nexus Venture Partners, Intel Capital, and Kalaari Capital.

Despite such strong backers, Snapdeal is increasingly losing relevance among customers and needs to find its unique selling proposition (USP) soon.

“Snapdeal has been having an identity crisis for the last couple of years,” said Sanchit Vir Gogia, chief analyst at Delhi-based Greyhound Research. “Flipkart has the advantage of a strong logistics infrastructure that they have developed in-house. And Amazon has long years of experience and deep pockets. But Snapdeal has not solved the logistics problem and it will suffer because of the lack of ecosystem.”

Flipkart vs Snapdeal

Snapdeal was founded three years after Flipkart, which launched in 2007. Even six years after its inception, though, the company has failed to bridge the gap with its older rival. If anything, the gap has only widened in recent years.

The two companies do not share most of their financial figures publicly, but, based on available information, here’s how they stack up:

Valuation: Earlier this year, Flipkart was devalued by multiple investors to anywhere between $9 billion and $11 billion. Even then, it is valued higher than Snapdeal, which was reportedly worth $6.5 billion in February.

Funding: Flipkart is among India’s most-funded startups, having raised around $3.5 billion in 12 rounds, according to online startup database CrunchBase. Snapdeal has tapped the market 11 times, but could raise only $1.7 billion.

App stats: The number of downloads of Flipkart’s android app far outnumber those of the Snapdeal app. The Flipkart app is rated 4.2 on a scale of 5 by users on the Android Play Store; Snapdeal’s is a tad lower at 4.1.

Seller recall: Amazon is the favorite e-commerce brand among Indian sellers, followed by Flipkart, a study by New York-based market research firm Nielsen said in June. Sellers are important because firms with a greater variety of products attract more buyers.

The Amazon threat

Amazon, which launched its Indian arm in 2013—six years after Flipkart was founded and three years after Snapdeal—already has a formidable presence in the country.

The company’s investment commitment to India is now higher than the total funds raised till now by both Flipkart and Snapdeal together.

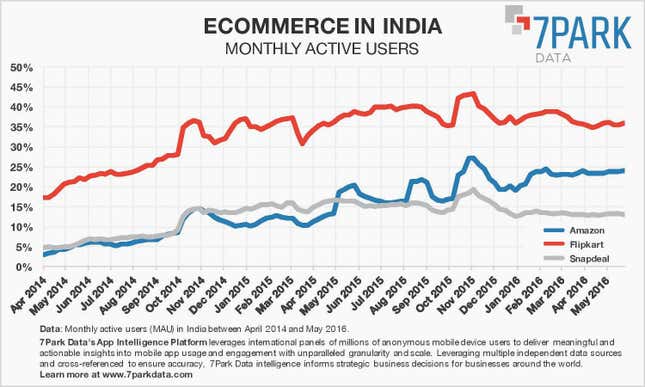

And it looks like Amazon is rapidly rising to the top.

On May 28, it had 24.1% monthly active users (MAU), way higher than Snapdeal’s 13.1%. MAU represents the share of mobile users in India who open a company’s app at least once in a given month.

Nikesh Arora, former president of SoftBank, which is an investor in Snapdeal, recently acknowledged Amazon’s threat to Snapdeal.

“In the last two years what has happened is that Jeff Bezos has come out and said he wants to win India at all cost. He will spend billions of dollars in India and that’s a new competitive fact. You have to figure out a way to compete with that,” Arora told The Times of India in an interview.

However, Snapdeal itself is confident about its position. “Amazon’s ‘threat’ to Indian e-commerce players is being overstated by media,” a company spokesperson told Quartz. “We spend less time thinking about what our competition is doing than thinking about what we can do for customers. “

Winner’s market

Historically, internet-based businesses have often had a single dominant market leader—like Facebook in social networking and Google in search.

“I don’t believe the Indian market will be able to sustain two big domestic players and one big international player,” said Anindya Ghose, director of New York University’s Center for Business Analytics. “In about three years, I believe, the Indian market will have to consolidate into one international and one domestic player. So it will be Amazon, and either Flipkart or Snapdeal.”

Based on current data, then, it is not hard to call the winner among Flipkart and Snapdeal.

However, Arora, who was on Snapdeal’s board until recently, disagrees on this count.

“In India, you will have a dominant player and others will exist, too. It won’t be a winner-takes-all market, either in e-commerce or in ride-hailing,” Arora told a newspaper. “The question is who will be the big and the small players, (and) with what market share?”

At Snapdeal

In the meantime, Snapdeal, like rival Flipkart, has been grappling with internal challenges.

Among other things, the company has missed its sales targets. Snapdeal’s GMV of around $4 billion in March 2016 was far below CEO Bahl’s $10 billion target.

There have also been several top-level exits in 2016. In January, senior vice-president of marketing Srinivas Murthy resigned. In May, it lost its prized Silicon Valley hire Anand Chandrasekaran, who was its chief product officer. In June, the business head for electronics, Saif Iqbal, quit.

At the other end, the company is going slow on hiring. “We plan to remain very close to our current employee strength over this year,” a Snapdeal spokesperson said.

In May, The Economic Times reported that the company had scaled down operations in its regional offices at Bengaluru, Mumbai, Kolkata, and Hyderabad, and may even shut down a few if it fails to raise a fresh funding round. Snapdeal, however, trashed these reports as “incorrect, baseless and misleading.”

The company is attempting to tap into the talent pool in Silicon Valley. On May 30, Snapdeal said it has set up a data sciences centre at San Carlos, California, which will help it hire veteran data scientists who could help Snapdeal develop stronger capabilities around analytics and predictive behaviour.

To its credit, Snapdeal has been more aggressive in terms of acquisitions than rival Flipkart. The company is credited with the biggest acquisition ever in the Indian startup space—mobile payments startup, Freecharge, for around $450 million.

Since 2010, Snapdeal has acquired 13 companies, while Flipkart bought nine.

But experts are unsure if all these acquisitions will help Snapdeal find its mojo. “It is incredibly difficult to find a USP in e-commerce retailing. There is only so much one can fight on reducing costs and margins,” Ghose of New York University said.

We welcome your comments at [email protected].