30 May, 2008, dawned bright and clear in Patna, Bihar.

Pans were rattling and children were being coaxed out of beds and into school uniforms. It was early still, but the slum of Chandpur Bela was abuzz. People were gravitating towards one house—Shanti Kutir. A crowd was assembled and if you pushed in farther, you could see a youngish man in his shirtsleeves, who seemed the centre of all the hullaballoo.

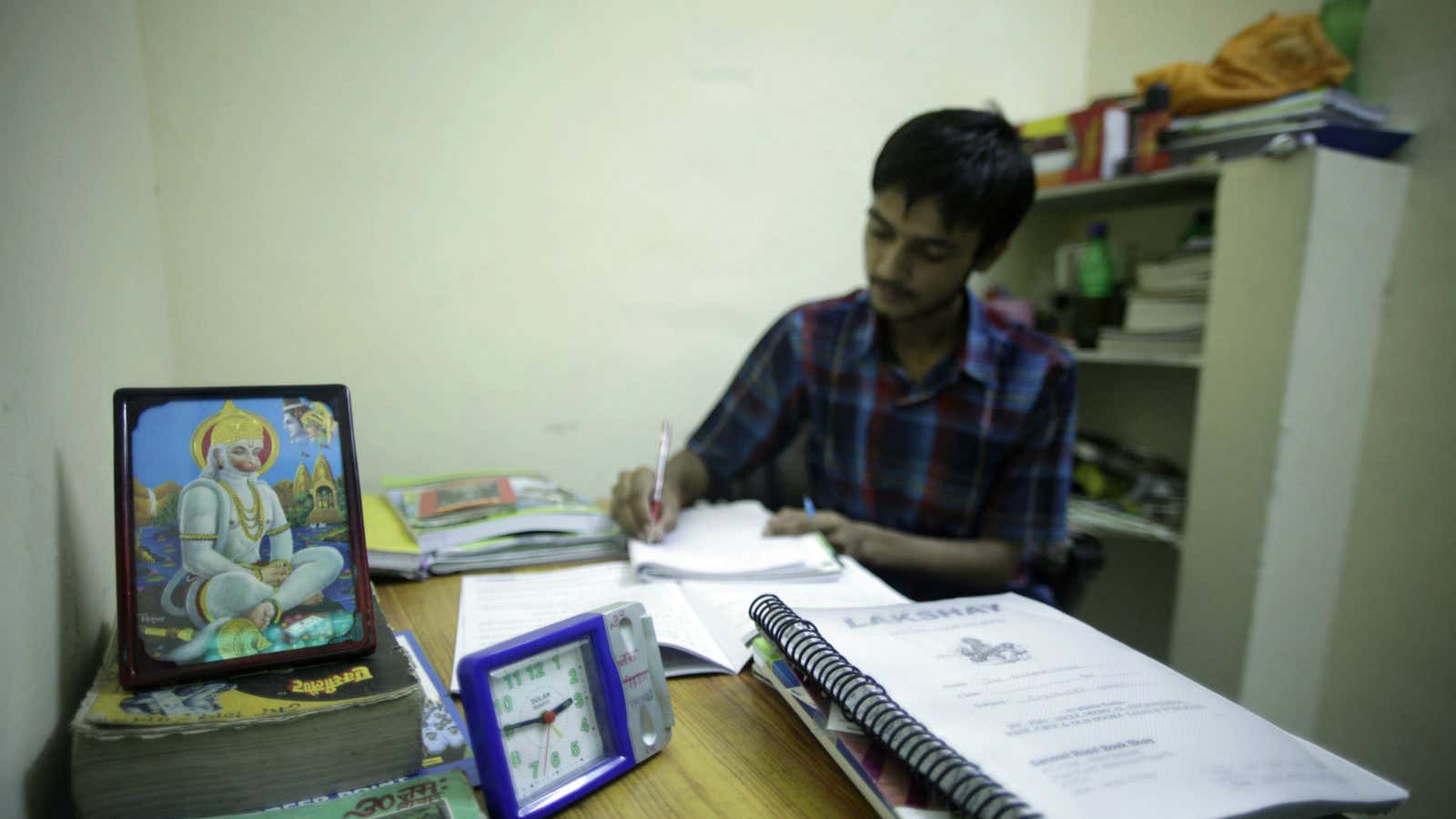

Anand Kumar was trying to talk to several people at once, answering questions, accepting their good wishes, and trying his utmost not to let his anxiety and nerves show. He had spent the previous year coaching thirty students for the IIT JEE entrance examination and finally, it was the day of the results.

It was the hour of reckoning. All thirty students had spent the night at Anand’s house, all too keyed up to get any sleep. Anand relived this year after year, yet the tight bundle of nerves in his stomach would not ease till he saw each student’s result. By 6 a.m., they had given up all pretence of sleep and started to get dressed. Jayanti Devi, Anand’s mother, prepared tea and soon the modest Kumar household was bustling with people.

Journalists started arriving as early as 6.30 a.m. Anand tried to explain to the first few that the results would not be out until 9 a.m., but soon gave up when he saw that they also wanted to capture the mood before the results were announced.

By 2008, Super 30 was a name to reckon with. Anand Kumar was hailed as a hero by People magazine, and his unique initiative, Super 30, was celebrated as one of the four most innovative schools in the world by Newsweek magazine.

Expectations were sky high as twenty-eight students had cracked the coveted IIT entrance exam the previous year, in 2007. Anand fielded calls from journalists who had grown close to him over the past few years as Super 30’s fame spread. I hope the result doesn’t disappoint, prayed Anand, as 9 a.m. ticked nearer. Outwardly, he was the picture of calm—reassuring the students, charming the media.

At about quarter to nine, Anand positioned himself in front of the computer screen with a list of roll numbers in hand. The students huddled around and more and more people pressed themselves into the cramped room. At 9.01 a.m., Rakesh Kumar was in! A cheer went up, Rakesh was thumped on the back, a journalist surreptitiously tried to lead him outside so he could get an interview.

Anand Kumar still had twenty-nine more names to go. Everybody waited with bated breath as he keyed in the second roll number. But nothing happened. The server was jammed. Lakhs of aspirants were simultaneously trying to check their scores. A few minutes later, Jai Ram had made it through! And now it was eighteen on eighteen.

Anand was perspiring freely but a hint of a smile played on his lips. He went on checking result after result—sometimes it would pop up immediately leading to raucous cheers and in other moments the error page would come up. Nearly an hour and a half later, it was just Anand and Ranjan Kumar, the thirtieth student left at the computer. “Chinta mat kariye, sab achha hoga (Don’t worry, everything will go well),” Anand said to the white-faced Ranjan. He had made it. He hugged Anand tightly and started laughing, and then crying, and then shouting garbled victory cries.

Anand was hoisted on shoulders, laddus were thrust into his mouth, flashbulbs went off, headlines for next morning’s papers were composed, and cries of ‘Anand sir zindabad’ reverberated. Deepu Kumar’s father had travelled from Supaul to be with them for the occasion. He was so overcome with emotion that he stood alone in a corner, weeping. Anand Sahay’s mother sat with Jayanti Devi making puris and jalebis. Journalists were trying to talk to as many students as they could. It was surreal. Anand could hardly believe it. Looking down at the shining, jubilant faces of his students, he felt a happiness so piercing that tears pricked his eyes.

He was so overcome with emotion that he stood alone in a corner, weeping. Anand Sahay’s mother sat with Jayanti Devi making puris and jalebis. Journalists were trying to talk to as many students as they could. It was surreal. Anand could hardly believe it. Looking down at the shining, jubilant faces of his students, he felt a happiness so piercing that tears pricked his eyes.

History had been made. Super 30 had achieved a cent per cent result.

Excerpted with permission from Biju Mathew’s Super 30: Changing the world 30 students at a time, published by Penguin India. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.