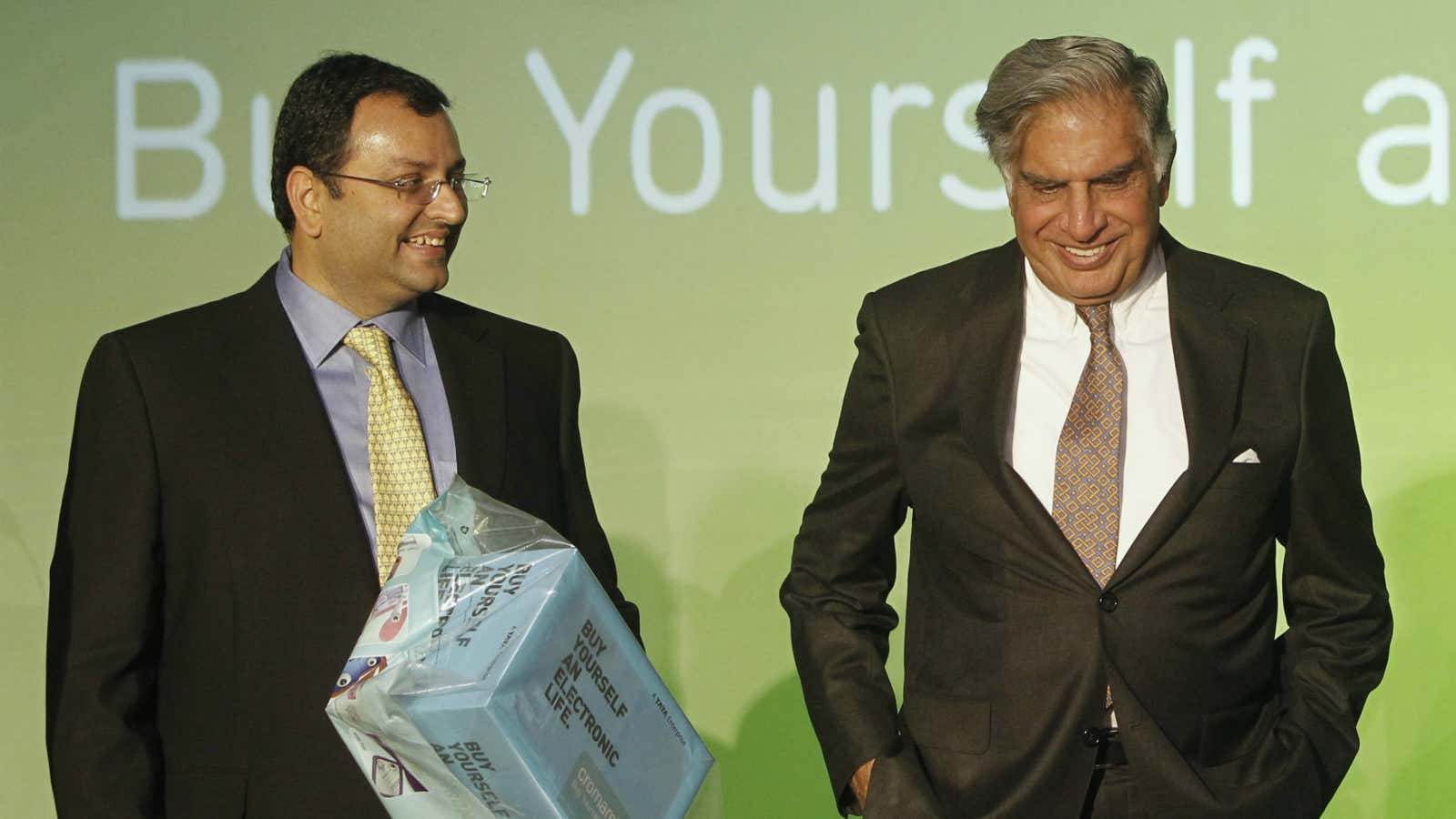

Cyrus Mistry has just been replaced by the man he was chosen to replace.

In November 2011, amid much speculation, Mistry was declared Ratan Tata’s handpicked successor as the chairman of Tata Sons, the holding company of the sprawling Tata Group. It was also announced that the Irish citizen of Indian origin would have the luxury of shadowing Tata for a year before filling in the rather large shoes of the veteran businessman starting December 2012.

The decision came after much deliberation and vetting, over 15 months, with a five-member selection committee considering a star-studded list of Indian and international business executives for the job.

Initially, Mistry, too, was a member of the selection panel but later dropped out to become part of the candidate pool. By then, Mistry had already been a member of the Tata Sons board for five years. His father—construction magnate Pallonji Mistry—was, and remains, the largest individual shareholder in the Tata Group.

A civil engineer from Imperial College, London, and an alumnus of the London Business School, Mistry was reportedly competing with a dozen others, including Deutsche Bank’s one-time star banker Anshu Jain, former Vodafone CEO Arun Sarin, and a few in-house candidates.

In the end, Mistry is thought to have emerged on top due to a handful of factors. These included his relatively young age (he was then 43), his expertise, particularly in engineering and finance, and his personal relationship with Ratan Tata.

“There has always been a strong chemistry between the two,” JJ Irani, former Tata Sons director, told the Business Standard newspaper in 2011. “In board meetings, Mr. Tata would often seek out his advice.”

At the moment, it is difficult to fathom exactly what happened since Mistry’s appointment to the board of Tata Sons—the leadership of a conglomerate unused to dramatic decision-making—to show the incumbent chairman the door.

In typically cryptic corporate-speak, a company spokesperson said that the “board and the principal shareholders in its collective wisdom took this decision, which they thought may be appropriate in the long term interest of Tata Sons and the Tata Group.”

Although there’ve been no significant upheavals during his term, there has been growing criticism of Mistry’s middling performance since taking over. “Nearly four years into Mr. Mistry’s tenure, the listless performance that could once have been blamed on things like slowing Chinese demand seems to be entrenched,” The Economist said, in a scathing indictment, earlier this year.

Indeed, the largest constituents of the Tata Group, which straddles over 100 operating companies covering everything from salt to software, have posted mixed numbers under Mistry’s watch.

Revenues of Tata Motors, the biggest contributor to the group in terms of sales, grew 5% in the 2015-16 financial year, largely due to the solid performance of Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), the British carmaker acquired by the group under Mistry’s predecessor.

Tata Steel, the second-largest contributor to the group’s total sales, saw revenues drop 16% primarily because of the macro-economic environment in Europe and the UK. Tata Steel Europe, a subsidiary, is the second-largest steelmaker in Europe. Even as Mistry’s selloff strategy was being applauded by analysts, he was unable to find a buyer for Tata Steel Europe.

Meanwhile, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), India’s largest IT services firm, posted a revenue growth of 7.1% in 2015-16. TCS has been the group’s cash cow but the past few months haven’t been great for Indian IT firms, given the blowback from Brexit. The IT behemoth, like its peers, has been struggling with clients becoming ever more cautious on spending (pdf).

The numbers show that the group isn’t in dire straits. But it hasn’t helped that during the four years at the helm, Mistry was also firefighting a raft of issues: the steel unit’s downfall, the messy telecom tussle with Japan’s Docomo, reviving the domestic fortunes of Tata Motors, and figuring out the tricky aviation business in India.

For all the celebration around his coronation four years ago, Mistry doesn’t seem to have taken the lumbering Tata Group in any new direction. There’s been no grand vision that he spelt out, no clear roadmap of the path ahead.

Now, it seems, he’s simply run out of time.