In most human cultures, the birth of a child is an unambiguously happy event. This moral framework does not, it seems, apply to some sections of social media, where for the most part of Tuesday, Tweeters bemoaned the birth of a new Bollywood baby. Born to A-list film stars Saif Ali Khan and Kareena Kapoor, the boy had been named Taimur–a highly objectionable christening for some, given the name’s association with a 14th century Turkic king and one the world’s most successful conquerors.

What was wrong with Taimur? Social media users were ostensibly objecting to the brutal nature of his conquests. Of particular concern was Taimur’s campaign against his fellow Turkics, the Tughlaq Sultanate of Delhi. Conducted in 1398, the Timurid invasion eventually led to the sack of Delhi city where, by some accounts, the entire population of the city was massacred.

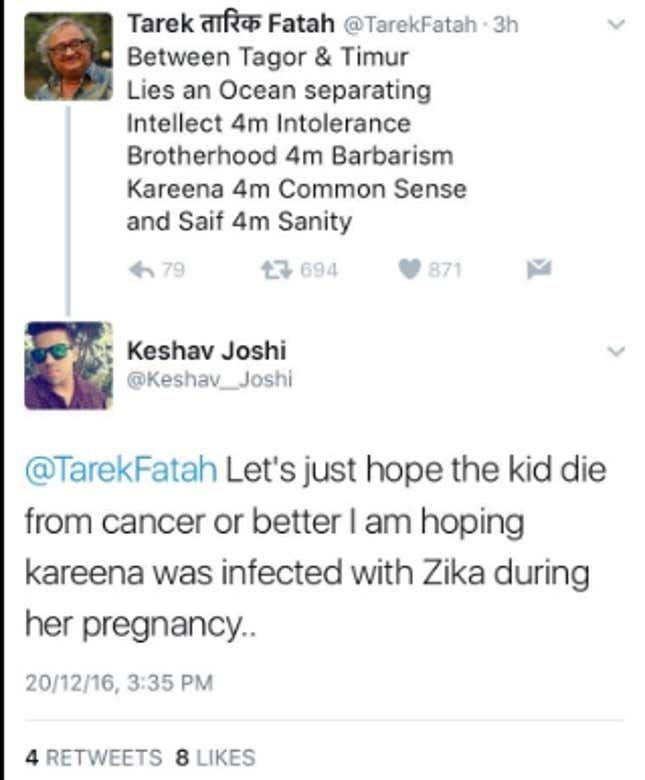

So deeply felt was this sack that 700 years later, Indians on Twitter would call the new-born baby a “terrorist”, a “jihadi,” and in general wish harm upon it.

While it may be easy to dismiss this as the work of trolls, the frankness of social media provides us an important window to attitudes that might otherwise not be aired publicly. With Hindutva in the ascendant, this incident shines a bright light upon how India’s medieval age is treated with a mixture of ignorance and paranoia by those who follow this ideology.

Hindutva pushes a narrative of ahistorical Muslim rule and then, is the first victim of its own misrepresentation. This distorted image of Muslim conquests projected by Hindutva creates a deep inferiority complex right at its centre. So much so that it was eventually expressed as tragi-comic social media rage against a day-old infant.

Heroes and villains

Historical narratives are tricky things to construct, especially when people want to superimpose moral lessons on them. Who is a hero and who isn’t is extremely subjective and even more so when one goes as far back in time as the 14th century. The past truly is a different country and to make it fit modern standards of morality a fair bit of invention needs to be indulged in.

Let’s take a force that is near-universally seen as the good guys in popular Indian history: the Marathas. The Marathas were successful towards the end of the Mughal period, building up a confederation over large parts of the subcontinent. Of course, this was done through war and conquest, and in the chaos of the Mughal twilight, contemporary accounts of the Marathas are often rather negative, cutting across what we would today see as “Hindu” and “Muslim” sources.

In the 18th century, the Marathas invaded Bengal, killing, by one account, four lakh Bengalis. Repeated raids and conquests of Gujarat were also, as almost everything in medieval India, a rather violent affair. In another case, Maratha armies raided a thousand-year old Hindu temple to teach Mysore sultan Tipu Sultan–who was its patron–a lesson. The Brahmin Peshwa rulers of the Maratha state enforced untouchability so brutally that BR Ambedkar actually saw their defeat at the hands of the British to be a blessing.

Contemporary accounts of the Marathas in Bengal are obviously far from flattering. Similarly, as late as 1895, there were strong objections in Gujarat to the plans of Bal Gangadhar Tilak to institute a Shivaji festival across India, with the Deshi Mitra newspaper of Surat disparaging it as a “flare up of local [Marathi] patriotism”.

India’s medieval period did not have the sort of nationalisms and community mobilisation that modern India would see under the Raj. As newspapers and technology knit the people of India together, a Hindu consciousness would revise the image of the Marathas as “Hindu.” Calcutta city’s intelligentsia at the time, in fact, celebrated a Shivaji festival and the city still has statues of Shivaji. Gujarat, where Hindutva has been a powerful political force for decades now, has adopted Shivaji with even more gusto, building statues in cities like Surat, which, ironically, were sacked by the Maratha chief early on in his career. This confusion is nothing new. Today, Punjabi Muslims in Pakistan see themselves as inheritors of the Mughals but in 1857 signed up enthusiastically for the East India Company’s armies to defeat the Mughal-led revolt against the Raj.

That which we call a rose

Naturally, then, the name Shivaji or Bhaskar–a Bhaskar Pandit led the Maratha raids on Bengal–are hardly taboo in modern India, given this modern narrative of the Marathas.

It is the same for Ashoka or Alexander, both of whom led bloody campaigns but whose names are common now even among the peoples they conquered. Sikandar, the Persian version of Alexander, is a common name across Iran and the subcontinent–a Bharatiya Janata Party parliamentarian’s son is, in fact, named after the Macedonian conqueror. Moreover, one would assume Ashoka carries no particular taboo in Orissa in spite of the Kalinga war.

In fact, this linking of a name to a supposed historical villain is a particularly egregious example of just how puerile Hindutva can be. It is a bit silly to think that someone would be outraged over the fact that a baby is named Joseph just because of Stalin’s role in the Soviet Union or that the name Manu would be taboo simply because someone named Manu was supposed to have authored the casteist Manu Smriti, a book of law linked to India’s crippling 2,000 year old system of caste apartheid.

This near-comical understanding of history, though, is not a new thing for Hindutva. The ideology has built a curious understanding of India’s medieval period, which it sees primarily through the lens of supposed invasions by Muslim kings and emperors. The founder of Hindutva, Vinayak Savarkar, would, for example, even use this grievance to validate modern wrongs–in one case justifying the use of rape as a political tool. Prime minister Modi, a lifelong member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, has often claimed India has suffered from 1,200 years of slavery.

Inventing an inferiority complex

This rage is, of course, largely ahistorical. Taimur, for example, finds little mention in historical works written by Hindus at the time or even hundreds of years after. In fact, his negative image is taken solely from Muslim writers, given that his brutal invasions were led almost exclusively against Islamic empires such as the Ottomans and the Mamluks of Egypt and Syria. Ironically, even in India, his invasion targeted what Hindutva would characterise as a Muslim, and therefore “foreign,” dynasty: the Tughlaqs.

However, the invention of this distorted history has had a rather deleterious effect on the Hindutva mind. Tales of a “thousand years of slavery”, as one could very well imagine, create a sort of mass inferiority complex. Even in this case, for example, as important a driver of rage as the name “Taimur” was the incipient anger at the fact that a Hindu woman, Kareena Kapoor, had married a Muslim man, Saif Ali Khan. The shadow of so-called love jihad, which once was a Bharatiya Janata Party policy position itself, only ends up harming Hindu women, given that it assumes they themselves aren’t free to make their own choices, romantic or otherwise.

This mass self-flagellation, a near masochistic nurturing of grievance, produces a highly distorted modern politics, showing how far Hindutva is from assuming any mantle of intellectual leadership, in spite of capturing political power at the federal level in India. An ideology that needs to pick on a little baby to prove its spurs has a long way to go before it can sit at the high table.

Final point. If this controversy forces some Hindutava ideologues to pick up a book and read the history of Taimur, we might be in for another storm. Taimur’s heir and the next ruler of the Timurid dynasty was a man named, well, Shah Rukh.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.