America, be warned: As the Trump administration moves to clamp down on H-1B visas, the US has a lot to lose.

Opponents of the H-1B program, which allows skilled foreign workers to be employed in the US for up to six years, say that it favors foreign workers over American ones, particularly when it comes to US-based technology jobs. A recent Goldman Sachs report, for example, found that while less than 1% of all US jobs go to foreign workers, more than 12% of tech jobs do. Tech companies have been accused—perhaps unfairly (pdf)—of exploiting the visa program to bring in cheap labor.

Nowhere is the threat to the H-1B program greater than in India, whose young people continue to pour into the US to study. Of the 1 million international students enrolled in American institutions last year, more than 15% were Indian, according to the Institute of International Education. Among the foreign-born talent allowed into America each year, Indians consistently account for the largest share of H-1B visas.

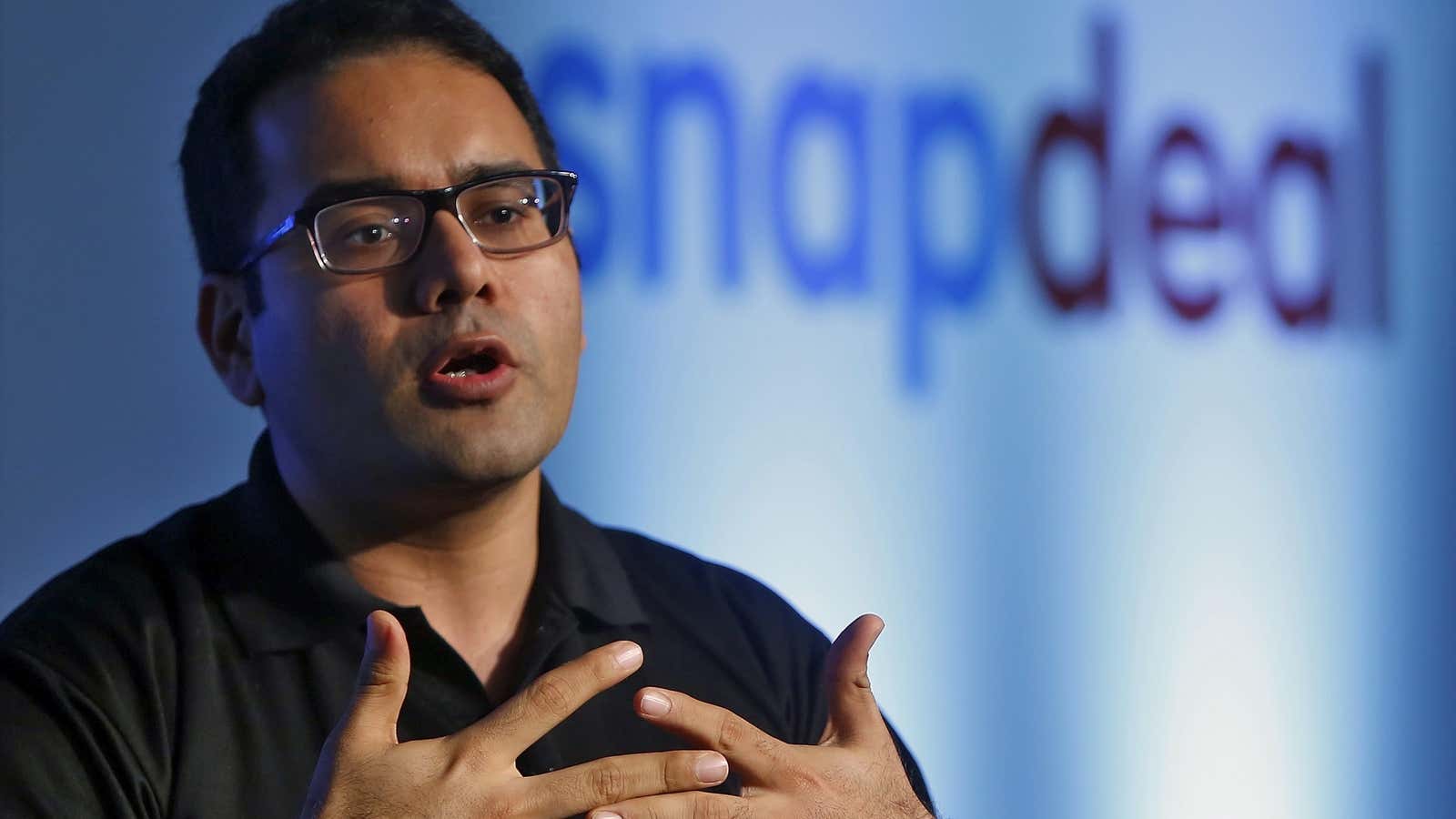

But for every H-1B granted in the US, two are rejected. Only a third of the hundreds of thousands of H-1B applicants actually secure a work visa each year—and those odds stand to get worse under Trump. Such a shift could affect American companies’ ability to hire talented foreign workers and their inclination to come to the US. Some of these workers carry the potential to become the biggest entrepreneurs of their generation. For example, Snapdeal’s CEO Kunal Bahl.

One of India’s biggest domestic e-commerce firms, Snapdeal may never have been formed if Bahl had been able to work for Microsoft.

In 2007, after graduating from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, Bahl secured an engineering role with the Seattle-based tech giant but did not have any luck with the H-1B lottery and had to return home to India. Three years later, Bahl and his friend Rohit Bansal launched Snapdeal.

India’s growing middle class, and their rapid adoption of the internet and smartphones, have set Snapdeal on a path to profitability. Today, the online marketplace ranks among the top contenders in e-retail, competing against the likes of Amazon and Bengaluru-based Flipkart. Backed by several marquee investors like Japan’s SoftBank and China’s Alibaba, Snapdeal has more than 300,000 sellers and over 50 million users. A year before assuming the presidency, Donald Trump himself referenced Bahl as an example of talent lost due to the US’ haphazard visa setup.

Bahl is not the only one to leave Silicon Valley for India. A handful of unicorns—private startups valued at more than $1 billion—founded in India were developed by US-educated entrepreneurs. Aside from Snapdeal, two more companies out of the nine India-based startups listed in Wall Street Journal’s Billion Dollar Club also have founders who studied in America: Sandeep Aggarwal, the founder of Gurgaon-based online marketplace portal Shopclues, got his MBA from Washington University in St. Louis. Mobile advertising giant InMobi, which is giving Google and Facebook a run for their money in India, was created by Harvard Business school graduate Naveen Tewari.

This isn’t just a failure of the US visa program: India is also the world’s fastest growing market. Ernst and Young has ranked the country as the world’s third-best for technology investments, and India has also successfully lured back some of its own best exports. Peeyush Ranjan and Punit Soni left their Google gigs for Flipkart in 2015, and Facebook’s Namita Gupta moved to Delhi-based restaurant listing site Zomato the year before. While talent-poaching may not cripple tech giants anytime soon, the allure of a powerful emerging market, combined with a skills shortage in the US and a crackdown on visas, could stop the next startup before it’s even had a chance to grow.

“There is a serious dearth of engineers here,” says Biju Ashokan, a Carnegie Mellon graduate who founded San Francisco-based real estate networking platform Agentdesks in October 2014. Ashokan himself is on an O1 visa, granted to individuals with extraordinary talent, but has long-term plans to bring his company’s Indian employees (currently located in Bengaluru) to the US to work on the H-1B category. Those plans are now in limbo. Ashokan says the skills shortage in the US has already pushed the average pay for engineers to $150,000-plus. Stricter visa requirements would only exacerbate that problem—perhaps the next Agentdesks wouldn’t be founded in America at all.

“We should harness the talents of foreign-born entrepreneurs and students to benefit our economy and our communities,” says Leezia Dhalla, communications associate at FWD.us, an immigration reform lobby set up by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg to work toward more inclusive policies. “Rather than pushing them to other countries to compete against us.”