Late in April, when the union ministry of human resources development (HRD) announced that officials of 32 state and central boards of education had decided to scrap the moderation of marks—also known as the grace marks policy—from 2017, school teachers across cities felt conflicted.

Most agreed that the practice had to go. It involves giving extra marks to students to compensate for errors in the question paper or difficult questions. It is also used to standardise markings when different students get different sets of questions for the same exam.

Teachers say it is also the reason for the unrealistically high scores, the steep rise in college cut-offs or the minimum scores required for admission, and the resultant stress among students.

Yet, they advised caution.

With board results and college admissions inextricably linked, such a reform would be tenable and fair only if all boards adopted it together. They warned that without uniformity, students from boards that follow the moderation policy would have higher marks and claim most of the undergraduate seats in central institutions like Delhi University, while those from boards without moderation would be left behind.

That is precisely what might happen this year.

On Tuesday, responding to a petition filed by a parent challenging the Central Board of Secondary Education’s (CBSE) decision to not moderate results this year, the Delhi high court (HC) ruled that the board has to retain moderation for this year. The CBSE, which has 18,500 affiliated schools, has so far been silent on whether it will challenge the decision or follow it. Earlier, as state boards began declaring their Class 12 exam results and it became clear that there was no consensus over marks moderation, a panicked CBSE sought special consideration for its examinees from Delhi University. Ironically, the April meeting of 32 boards had taken place on the CBSE’s initiative.

No matter what the CBSE decides, some students will suffer.

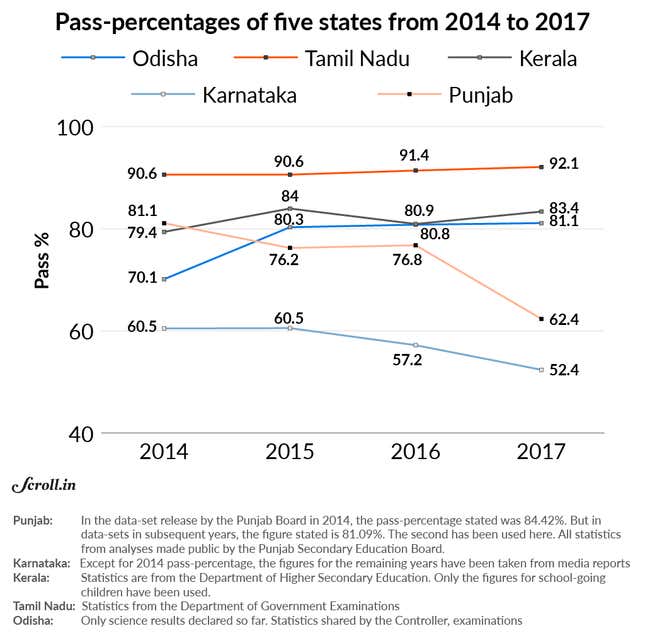

An analysis by Scroll.in of the results of some states shows a wide gap in the exam outcomes in states that have abandoned marks moderation this year and those that have not.

Pass percentages

On May 15, the school education secretary, Anil Swarup, tweeted: “Rajasthan [Education] Board becomes the [third] one after Karnataka [and] Punjab to announce results without spiking of marks in the name of moderation.”

The three state boards have registered decreases in pass-percentages—share of students clearing the exam—after they ended moderation.

In Karnataka, it dropped from 57.2% in 2016 to 52.4% this year. In Punjab, the drop was sharper—from 76.8% in 2016 to 62.4%. Even on the board’s merit list, the change is evident: In 2016, over 341 candidates scored over 95%. In 2017, this number was down to just 126, though three students scored 100%.

Asked what they propose to do, now that CBSE may reintroduce moderation, the Punjab School Education Board chairman, S Balbir Singh Dhol, said: “We will study the copy of the decision and then decide.”

Rajasthan’s case is more interesting. Patted on the back for not moderating the marks this year, the Rajasthan Board of Secondary Education’s chairman BL Chaudhary said they “never did it” anyway. Rajasthan has declared Class 12 results for science and commerce streams only for this year, and the combined pass-percentage is a little over 90%.

Neither Rajasthan nor Karnataka has made public the number of its candidates who scored 90% or above in Class 12—in many ways a better indicator than pass-percentages of the impact of moderation on results and college cut-offs.

But each board has been doing its own thing and not following the CBSE.

Rising pass-percentages

Those who expected the pass-percentages to drop uniformly were disappointed and alarmed.

In Tamil Nadu’s state board schools, it increased from 91.4% in 2016 to 92.1% in 2017. Over 46,000 examinees have scored over 90%.

In Kerala, it has risen by three points to 83.4%. The state board has awarded A+, or marks over 90%, to 11,768 students—1,898 more than last year. “We have not moderated but done only subjectivity correction,” said an official of the directorate of higher secondary education, Kerala, asking not to be identified. He then proceeded to define “subjectivity correction” in the practically same terms used for moderation. “We adjust marks when the questions are too difficult or marking too strict,” he said.

In Odisha, where the state has only declared science stream results so far, the pass-percentage rose by one point. BN Mishra, controller, exams, explained that they followed their standard practice of moderating up to three percentage points this year too.

Given the differing responses to the Centre’s call to abolish moderation, CBSE students have welcomed a reset to the old system.

“I am relieved,” said Sumanyu Bhatia, a Class 12 science student at Delhi’s Ahlcon International School. “Without moderation, CBSE students would have scored low marks and been unable to get into Delhi University. The seats would have gone to [students of] other boards. My classmates in humanities and commerce were especially worried because admission for them [typically] does not involve entrance tests.”

Another Class 12 student, Akankhya Behera, in CBSE-affiliated Delhi Public School, Bengaluru, too was pleased with the HC’s decision. “I do think the practice of awarding grace marks is unfair but CBSE should not have changed the policy after the exams were held,” she said. “Also, all boards should change together, or none at all.”

School principal Mansoor Ali Khan admitted that while the HC’s direction may protect his students, it may put those following the Karnataka board at a disadvantage.

Knee-jerk reaction?

Many principals and school association members across cities had anticipated the mess, even while agreeing that some intervention was necessary to arrest marks inflation.

While the government initially suggested that the decision to not moderate was a done deal, HRD minister Prakash Javadekar himself walked back on those statements. He tweeted that the states have been left to decide what to do about moderation.

“A coordination committee meeting is only that,” quipped KC Kedia of the Mumbai-based Unaided Schools Forum, an association of Maharashtra’s private schools. “The boards are independent. The decision at the meeting was never legally-binding.”

Ashok Pandey, chairperson of the National Progressive Schools Conference and principal of Ahlcon International, pointed out that education is in the concurrent list, with the centre and states sharing governance. State boards are not obliged to follow the CBSE’s lead.

“This was a knee-jerk solution,” said Khan. “The government should have taken more time, worked with all the boards and developed a uniform policy—not just for moderation but for evaluation itself.”

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.