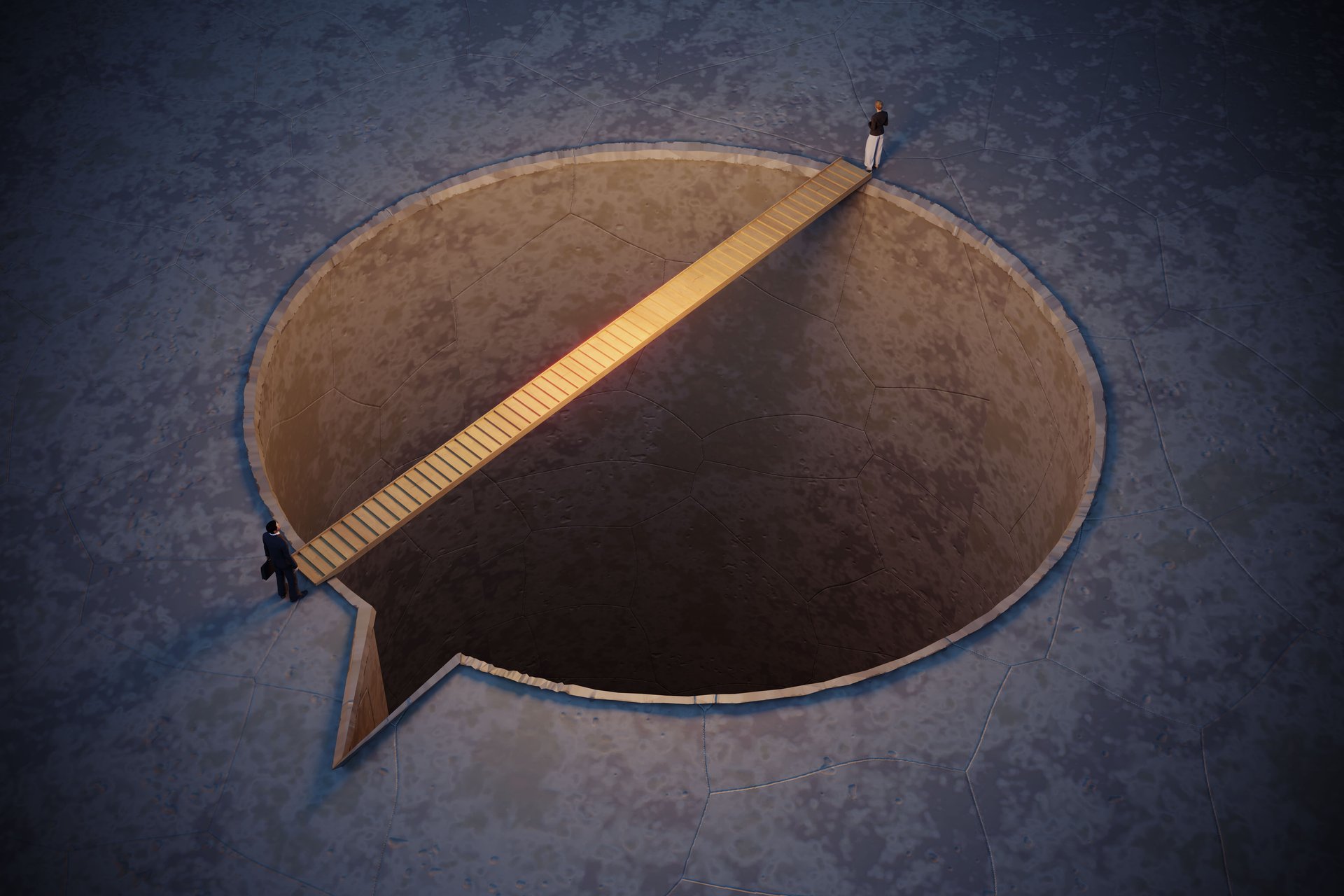

The Invalidation Triple Threat is ruining your relationships at work and at home

An invalidation pattern is often the biggest threat to trust erosion in people’s relationships, but it disguises itself as harmless disagreement.

Eoneren / Getty Images

“Invalidation” is one of those words that’s easy to dislike and dismiss. Sometimes it sounds a little too feelings-y or like a therapeutic buzzword our relationship partner might use when they’re mad at us for expressing disagreement with them.

Suggested Reading

This can result in people confusing the idea of validation with agreement, which is a costly mistake — perhaps the greatest threat to the quality of our family and workplace relationships.

Related Content

The Invalidation Triple Threat might be the biggest, most important idea I talk about in my relationship coaching work with individuals and couples because it so often sneaks up on people and ruins their personal lives.

An invalidation pattern is often the biggest threat to trust erosion in people’s relationships, but it disguises itself as harmless disagreement — especially in the workplace where disagreement and arriving at the best idea are often encouraged.

We can all agree that we should be able to reasonably disagree about all sorts of ideas. Because many people are comfortable expressing disagreement, and because many people don’t ever think about the distinction between disagreement and invalidation, it turns out that people experience invalidation often.

Over time, it will end marriages and long-term romantic partnerships.

The personal stakes might be less in your workplace relationships, but if conversation, idea expression, and occasional disagreements are a routine part of your work day, developing this subtle relational skill can radically change how you are perceived and help you have much more successful relationships.

How the Invalidation Triple Threat works (against you)

It typically begins with someone — often our relationship partner but can just as easily be an employee or coworker — coming to us to communicate a problem or negative experience they’re having. They’re trying to tell us that something is wrong.

Our most common responses are often the biggest threat to the quality of your personal and workplace relationships.

Invalidating response #1: I don’t think about this the same way that you’re thinking about this

An employee, a coworker, a friend, one of your children, or your romantic partner comes to you to say that something is wrong. You think about it for a nanosecond and realize that you don’t agree with them, and then you say that out loud.

“I don’t think about this the same way you think about this, therefore I judge your overall experience on the matter to be wrong. Try thinking about it this new way — the way that I’m thinking about it,” you might say.

The unintended consequence of this conversation pattern is that the person who is trying to tell you about a problem they’re having is met with a response that’s more or less: Because I don’t think about this the same way you think about this, I’m not going to treat this with importance or care, because it doesn’t meet my standard for what’s important. I only treat what matters to you with respect when it aligns with what I care about, otherwise you’re on your own.

A little bit of trust erodes.

Invalidating response #2: I don’t feel about this the same way that you’re feeling about this

Once again, an employee, coworker, friend, one of your kids, or your romantic partner comes to you with the aim of telling you that they’re having a problem. That something is wrong. You think about it for a nanosecond and realize that you don’t feel as passionately about what they’re saying as they do. You might even calculate that they’re being too sensitive or overreacting, and then you say so:

“I don’t feel about this the same way you feel about this, therefore I judge your overall experience on the matter to be wrong. Try feeling about it this new way — the way that I’m feeling about it,” you might say.

Similarly to the invalidating response #1, the unintended consequence of this conversation is that the person informing you of the issue they’re having and possibly trying to recruit you to help them are receiving the feedback: Because I don’t feel about this the same way you feel about this, I’m not going to treat this with importance or care, because it doesn’t meet my standard for what’s important. I only feel strongly about the things you feel strongly about when I judge your concerns as valid, otherwise you’re on your own.

A little bit of trust erodes.

Invalidating response #3: Defensiveness

This time, someone is coming to you with a problem they’re having, and their experience suggests that it’s happening as a result of something you did or perhaps something you failed to do. Your split-second reaction might be that they’re judging you too harshly, or are unaware of some circumstances that rationalize or justify the decision you made leading to this outcome they’re unhappy about.

“Hey, stop blaming me, I didn’t do anything wrong. Let me explain,” you might say.

The unintended consequence of this conversation is that you prioritize your comfort and experiences more than the person coming to you for help and cooperation to solve their problem. Furthermore, rationalizing or justifying why you’ve done something which resulted in a negative outcome for someone else strongly implies that you may make that same choice again in the future.

Again, a little bit more trust erodes.

And the reason this is so problematic is because of how minor each of these incidents appears to be when viewed in isolation. Any one instance of this happening isn’t that big of a deal, and no one really thinks it is.

What turns out to be a big deal is when this pattern is reoccurring, and a little bit of trust erodes again and again and again, and then after 1,000 of these so-called little instances stack up, there’s no trust left between the two parties.

That’s when a self-respecting employee will find another job.

That’s when a self-respecting business partner will find someone and something else to invest in.

That’s when a self-respecting relationship partner will choose a life with less pain and more intimacy.

Building the relational skill of acknowledging how someone else can experience the same circumstances differently than you might is the first step. People who are deathly allergic to peanuts or for some reason have never liked the taste of caramel will always experience Snickers bars differently than someone who loves them.

This doesn’t require agreement. You probably think Snickers bars are delicious. You don’t have to agree that they’re not delicious. You just have to understand that if eating one might cost you your life, or delivers a flavor you’ve found off-putting your entire life, it makes sense to not want to eat one.

And then learn the language of validation: “I can totally understand why you have these feelings and needs, because…” as leading relationship expert and author John Gottman suggests in his book “The Science of Trust.”

As Esther Perel reminds us in “Mating in Captivity,” the art and skill of validation does not have to involve agreement. It simply has to honor and respect someone else’s lived reality.