In the spring of 1975, a college dropout and his childhood friend launched a tiny software company in Albuquerque with a singular mission: put a computer on every desk and in every home. Five decades later, Microsoft stands as a survivor of tech’s brutal evolutionary cycles, transforming from a scrappy BASIC interpreter vendor to an operating system kingpin, an internet also-ran, a stagnating giant, and now a cloud computing and AI player worth almost $3 trillion.

While many tech giants have risen and fallen — from Digital Equipment Corporation to Yahoo to BlackBerry — Microsoft has navigated multiple technological revolutions by making strategic pivots and occasionally cannibalizing its own successful products. This pattern of reinvention, occurring roughly once per decade, reveals insights about institutional adaptability that extend beyond the tech sector.

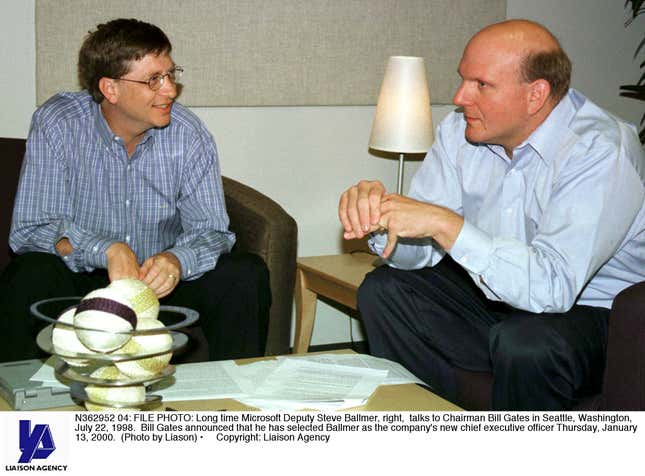

Microsoft’s instinct for reinvention was evident from its earliest days. When Bill Gates and Paul Allen founded Microsoft, they bet on software as the driver of the computing revolution while most tech companies went all-in on hardware. “Paul came to Bill and said, ‘Okay, let’s just go write all the software this thing will ever need,’” said Steve Ballmer, Microsoft’s former CEO, in a recent interview with Geekwire. This software-first vision positioned Microsoft as the connective tissue between hardware platforms rather than tying its fortunes to any particular machine.

The first major self-disruption came with the transition from MS-DOS to Windows. Rather than protect its near-monopoly in command-line operating systems, Gates invested heavily in developing Windows. The gamble was enormous — Windows 1.0 was widely considered a disappointment — but Microsoft persisted. By the mid-1990s, Windows had thoroughly cannibalized the DOS business that had built the company.

Another significant pivot came in 1995, when Gates issued his “Internet Tidal Wave” memo. Despite Windows 95's imminent launch, Gates recognized that the nascent World Wide Web threatened to make the operating system irrelevant. Microsoft’s initial response was sluggish — Netscape, the dominant browser startup co-founded by Mosaic creator Marc Andreessen, was quickly becoming the face of the internet era — but the subsequent pivot to everything internet was comprehensive.

“We were able to embrace it with everything we did,” said current CEO Satya Nadella in an interview on the Dwarkesh podcast in February, “whether it was HTML in Word or building a new thing called the browser ourselves and competing for it, and then building a web server on our server stack.”

The pivot worked, but this period also revealed that even Microsoft couldn’t predict all aspects of technological disruption correctly. “We missed what turned out to be the biggest business model on the web,” said Nadella, “because we all assumed the web is all about being distributed. Who would have thought that search would be the biggest winner?”

This blind spot allowed Google to emerge as Microsoft’s most formidable competitor and contributed to a period of stagnation in the 2000s. Under Ballmer’s leadership, Microsoft continued generating enormous profits but missed key technological shifts, most notably the mobile revolution, something Ballmer has acknowledged.

“I would have stopped the project that was Cairo three or four years earlier,” said Ballmer in the Geekwire interview, referring to what became Windows Vista. “We had basically a team of thousands tied up for eight years to put together a release that wasn’t as good as the one that preceded it.”

Microsoft’s cloud transformation began in the later Ballmer years but accelerated dramatically under Nadella. The shift to cloud computing required Microsoft to essentially abandon the software licensing model that had driven its profits for decades. “In terms of ascendance, it’s got to be the move to the cloud,” said Ballmer. “We had Office up and running. We had Azure. It’s not like things were in great shape, but we had some momentum.”

Nadella shifted Microsoft’s approach. Within weeks of becoming CEO in 2014, he released Office for iPad, ending the company’s strategy of using Office as exclusive leverage for Windows. He then accelerated Microsoft’s cloud investments, pouring billions into Azure data centers. The market responded — Microsoft’s value increased more than tenfold under Nadella’s leadership in his first ten years at the helm.

Today, Microsoft is attempting another reinvention with artificial intelligence. At first, the company’s $13 billion partnership with OpenAI and integration of AI across its product suite seemed to position Microsoft ahead of competitors. Wall Street initially rewarded this vision, but recent developments suggest this transformation may not be proceeding smoothly. The company has quietly pulled back on data center commitments, tensions with OpenAI have surfaced, and Microsoft’s stock has underperformed other tech giants despite its early AI leadership.

It’s still early days, though. Whether Microsoft can adapt to the AI era as successfully as it did to previous technological shifts remains an open question — one that could determine if the company’s next 50 years will be as notable as its first.