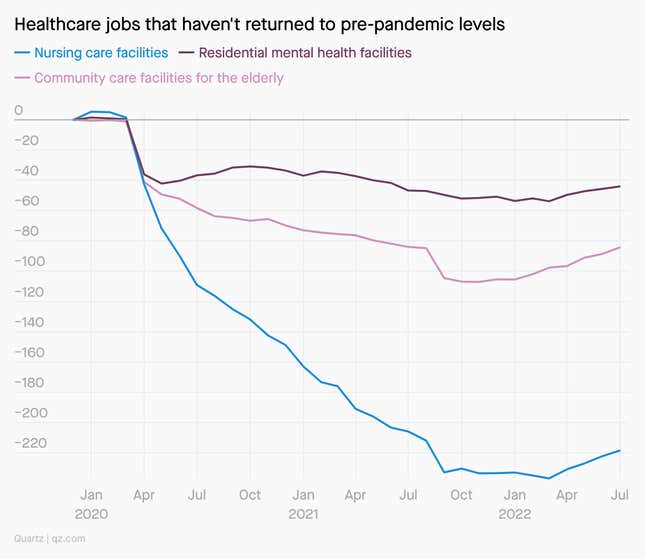

In February 2020, just before covid hit, there were about 1.6 million people (pdf) employed in nursing homes in the US. By July of 2022, less than 1.4 million were, according to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

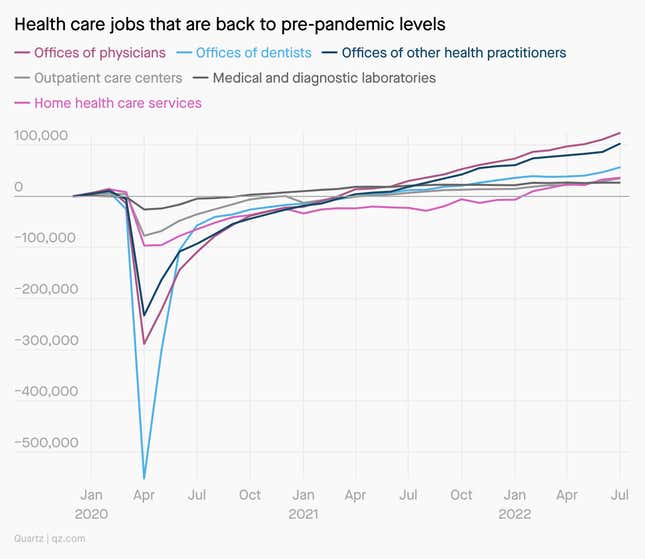

A sudden reduction of employment in healthcare affected all health sectors—from physicians’ offices to dentists to outpatient care services—as covid hit. But while most of these sectors recovered relatively swiftly, getting back to pre-pandemic levels, long-term care employment is still struggling to meet the needs of patients.

Nursing care facilities, residential mental health facilities, and community care facilities for the elderly have lost a combined 400,000 workers since the beginning of the pandemic, and even though the trend has reversed toward the end of 2021, the pace of recovery is too slow.

Nursing home workers have been quitting for years

The situation is especially dire for nursing homes, which were already struggling with personnel shortages before the pandemic, and have lost 15% of the workforce since February 2020.

The decline in nursing home employment was accelerated by covid, but it predates the pandemic. Nursing home staffers had been complaining of burnout and unfair working conditions and pay for years before the pandemic. But covid turned a trickle into a waterfall: Between 2015 and early 2020, the nursing home workforce shrunk by about 50,000, but by 2022, it had lost 200,000 more workers.

This is already having severe consequences. According to data from the American Health Care Association (AHCA) nearly 90% of nursing home providers report being understaffed, and about 50% are severely understaffed. Further, 98% report having trouble hiring new personnel, and 99% have had to ask their existing employees to work extra shifts, which is in turn likely to drive away the remaining personnel.

The AHCA also found that more than 60% of US nursing homes are cutting down the number of patients they can assist because they aren’t able to find the personnel, and that 71% of them struggle to find qualified, interested caregivers, despite offering wage increases and bonuses.

Research from University of California, San Francisco, suggests the situation will become even more dramatic in the coming years, with a projected shortage of 2.5 million long-term care (pdf) workers by 2030.