Last year, US customs officers seized over $4 million worth of fake chairs. It was the first year that the agency had ever seized containers-full of such unauthorized reproductions, thanks in part to a novel new training that’s turning port inspectors into design connoisseurs.

Over the past 18 months, a five-year-old consortium of furniture manufacturers and design firms called BeOriginal Americas has been training US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) officers to distinguish real Eames, Starck, and Mies van der Rohe designs from fakes, among others. It’s working: According to CBP’s Intellectual Property Rights Seizure Statistics report (pdf, p.5), in 2016, customs officials confiscated 42 shipments of unauthorized replicas worth an estimated $4.2 million. In the same report, the CBP claimed that their “furniture enforcement efforts have helped to protect over 8,000 American jobs” a figure calculated according to workforce data provided to them by US furniture manufacturers.

But they’re up against a vast knock-off industry. Labeled with nice-sounding terms like “reproduction,” “replica,” or “homage,” many designer chairs in offices, hotel lobbies, airports, restaurants and even big furniture stores are actually unauthorized copies. And while a knock-off Eames or Barcelona chair might seem like a harmless, budget-friendly addition to your living room, these illegal knockoffs threaten the economy and the environment, and erode the very meaning of design.

Imitating Eames

The iconic Eames lounge chair is among the most copied pieces of furniture. Designed by husband-and-wife team Charles and Ray Eames for the luxury furniture market, the leather and bent plywood recliner has become symbolic of good design taste and affluence. The recliner was originally conceived as a napping-and-reading perch for Hollywood director Billy Wilder, who wanted a handsome English club chair with the feel of “warm, receptive look of a well-worn first baseman’s mitt.”

Today, the Eames lounge is still assembled by hand in a Zeeland, Michigan factory following the same meticulous process that the Eameses took four years to perfect. The mid-century modern classic often appears on celebrity photographs, TV shows, magazine covers, and enshrined in MoMA’s permanent collection.

It was a sensation from the moment it was unveiled it on live television in 1956. But not everyone watching the Arlene Francis Home show could afford to shell out $310 (around $2,800 today). Inevitably, knockoffs surfaced in the market.

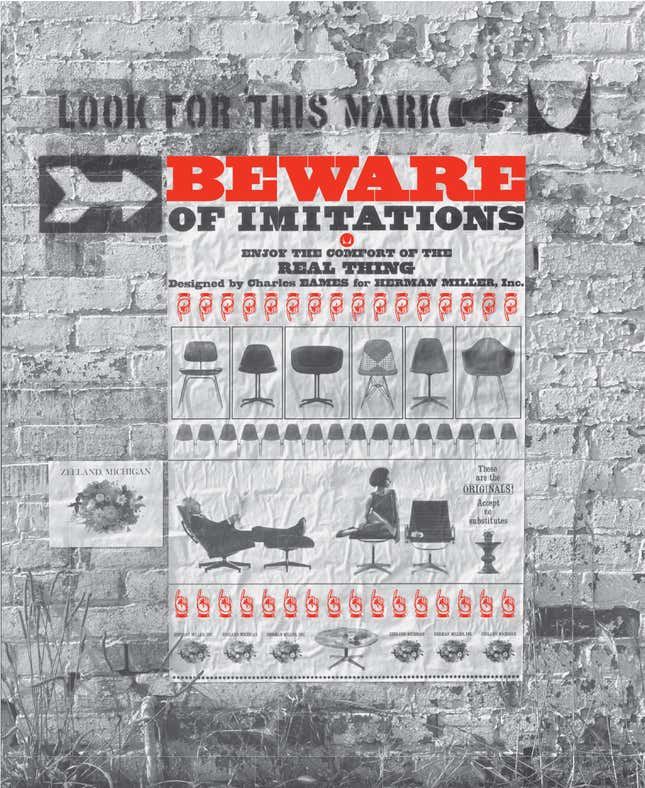

By 1962, imitations were so widespread the Eames took out a full page ad warning customers about fakes. The ad on the back cover of Arts and Architecture magazine instructed buyers to look for Herman Miller’s logo, the only authorized manufacturer of their chairs at the time. (Swiss manufacturer Vitra makes Eames furniture for the European and Middle Eastern market today.)

Today, e-commerce has made the job of policing fakes much harder. A quick search online yields hundreds of options, from Amazon, Ebay, Alibaba and various online retailers around the world. Brick-and-mortar shop Manhattan Home Design in New York City touts knockoffs that, according to one sales rep, “match or exceed the licensed product,” and even offers an instructional video on how to judge a good knockoff from a bad one. As with fake Rolex watches, there’s deep connoisseurship in the fakes business. Manhattan Home Design did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In the end, it all boils down to bargains. For just a fraction of the original Eames chair’s $5,000 price, customers can get the look. On Amazon, Eames knockoffs sell for as low as $749—that’s even cheaper than Vitra’s licensed 6-inch toy version of the Eames lounge and ottoman, which costs $795.

Protecting precious designs

Protecting intellectual property isn’t easy for furniture designers. For one thing, the bar is high: IP laws for furniture in the US don’t protect function, so designers have to prove a unique element in their design to qualify for a patent. Even if you get a patent, patent protections that apply in one region rarely apply elsewhere—not very useful in a global marketplace. Even members of the EU can’t agree on a standard duration on design patents.

In the US, the Eames lounge chair and other iconic designs are protected by what’s called “trade dress” rights. “Trade dress protects furniture designs that have come to be associated by consumers with a single source,” explains intellectual property attorney Michael J. McCue. The law protects the “commercial look” of well-known designs such as the Eames lounge chair or the Coca-Cola bottle for perpetuity, even when design patents have elapsed.

Few companies are above copying another’s designs. In 2012, the upscale US furniture company Restoration Hardware, which has something of a reputation for borrowing designs, advertised a metal chair called the “Naval” chair, identical to Pennsylvania-based chair maker Emeco’s well-known “Navy” chair.

A lightweight and virtually indestructible model made of recycled aluminum, Emeco’s chair was originally engineered for the US Navy during World War II. Later, the rugged chair (aka Emeco 1006) became a popular choice for police station interrogation rooms, prisons, and hospitals because of its reputation for toughness.

It takes 77 steps over 10 days to produce one Emeco Navy chair, with craftsmen moulding, welding and finishing it by hand in Hanover, Pennsylvania. The result is a $455 chair with a lifetime warranty. Made in China, Restoration Hardware’s heavier version costs just $129.

“The last thing I want to do is to spend our money in litigation,” says Emeco CEO Gregg Buchbinder. “But if you fail to react to something that grievous, you end up losing ownership within a short amount of time.”

That year, Buchbinder successfully sued to stop Restoration Hardware’s copies from spreading in the market. Last year, he also successfully sued to stop IKEA from mass producing copies of a Norman Foster-designed Emeco chair.

What’s wrong with knockoffs?

Companies who rip off classics benefit because they can skip the years-long product development phase and often have an easier time selling their versions because consumers are already familiar with the look. Large furniture companies like Ikea and Restoration Hardware, which mail millions of catalogues each season, can also disseminate far more information about a design than the original creator, adds Buchbinder. “The average consumer would think that’s the original chair.”

A little bit of copying can actually spur innovation, argue law professors Kal Raustiala and Christopher Jon Sprigman in the book Knockoff Economy. “Imitation only makes the fashion cycle run faster and forces the fashion industry to be ever more creative,” they write of clothes knock-offs. “When an original becomes a knockoff, it’s a signal to move on to the next big thing.”

Others argue that knockoffs can serve the original designer. Through what’s called the “piracy paradox,” copycats often help spread a designer’s work and increase the demand for it.

But good furniture designers are interested in durability, not novelty.“Built to last,” “timeless” and “heirloom” are the trade’s virtues. Charles’s grandson Eames Demetrios says that arguing for authenticity is difficult in a time when most consumers have little experience of making products by hand. “Most people when they think of the word ‘copy,’ they think of dragging a file from one side of a [computer] desktop to another,” observes Demetrios. “That makes us hard to have a conversation because at some level we have this feeling that a copy is the same thing.”

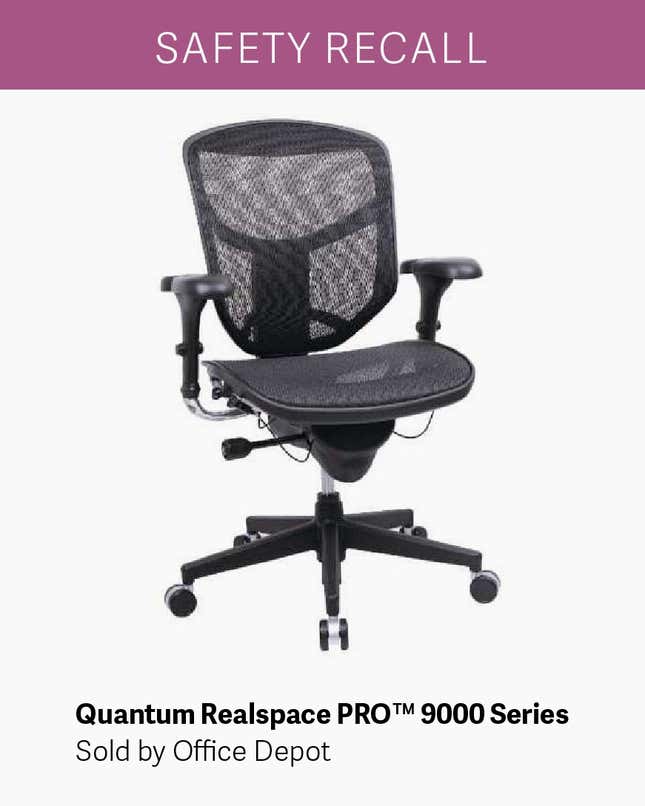

There are practical considerations too. Buying knockoffs also exposes consumers and companies to safety risks, warns Coleman Gutshall, Bernhardt Design’s director of global strategy and sourcing. Without a reputation to protect, counterfeiters can skirt product safety regulations or employ factories with questionable labor policies. Quantum, an ergonomic office chair sold by Office Depot that looks suspiciously like Herman Miller’s Aeron chair was found to have defective backrest bolts and caused back injuries.

The difference between design and style

“Copying something without consideration of quality is now an epidemic,” once said architect Benjamin Cherner to Dwell. “The world has been flooded with ‘stage props’—items that resemble useful objects but have minimal functionality.”

Buchbinder blames knock-off culture on a popular misconception of what “design” really means. “The design of the chair really starts with scientists, chemists and engineers working on the materials and the processes,” he explains. “There’s so much more to design other than the shape. I don’t think the average consumer understands that, they think they’re paying for the shape.”

Designer chairs are often advertised based on form, finish and material. But like all good design, furniture design is primarily concerned with looking for solutions for specific needs. Well-built office chairs, for instance, are engineered so they don’t tip over when the sitter leans back; the superdurable Navy chair emerged from the US military’s need for a deckchair that could “withstand water, salt air and sailors”; and the Eames lounge chair is obsessively designed for comfort. Knockoffs, while styled similarly, can fail to deliver solutions because counterfeiters are focused on mass producing and selling good-enough products cheaply and quickly. “In the end, a fake is designed for one thing: to be cheaper,” observes Demetrios.

There are indeed some very good knockoffs. But the energy spent aping another’s design would be better spent on creating an original design that responds to a new problem. Good design is never just about form. To appreciate the difference between an original and a knockoff is to understand the difference between design and style.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that the global counterfeit furniture industry had been estimated at $1.7 trillion. That figure is actually an outdated projection of the “economic and social impacts” of all counterfeit and pirated goods by 2015, according to the International Chamber of Commerce. It has been removed from the article, and the headline has been changed accordingly.