For those of us who cling to print, the topic of bookshelf organization seems to trigger a strong reaction.

Hanya Yanagihara, author of the 2015 novel A Little Life, found this out when she set off a mini firestorm among book-lovers with a throwaway comment in an interview. When her collection of 12,000 books was profiled in the Guardian, Yanagihara explained that she organizes her books alphabetically. “Anyone who arranges their books by colour,” she proclaimed, “doesn’t truly care what’s in the books.”

Her contempt was condemned by passionate color-coding shelfers as snobbery, and the comment sparked some book-Twitter backlash, with people challenging Yanagihara’s claims about her own shelf:

Why do we care so much about our shelving systems and those of others? Perhaps we just believe that the systems we’ve spent years perfecting are superior to others. Or maybe all that ire and passion is rooted in pride.

But there are plenty of ways to organize books other than alphabetical or by color. If you’re not yet deeply emotionally attached to any one method, or are looking to try a new one, here are a few suggestions garnered from an informal survey of friends and colleagues, starting with the most obvious:

Alphabetical

A fine, no-nonsense option favored by bookstores and libraries, as well as Yanagihara. The best part about organizing by author’s last name is that anyone who lives in or visits your home can use it, not just you.

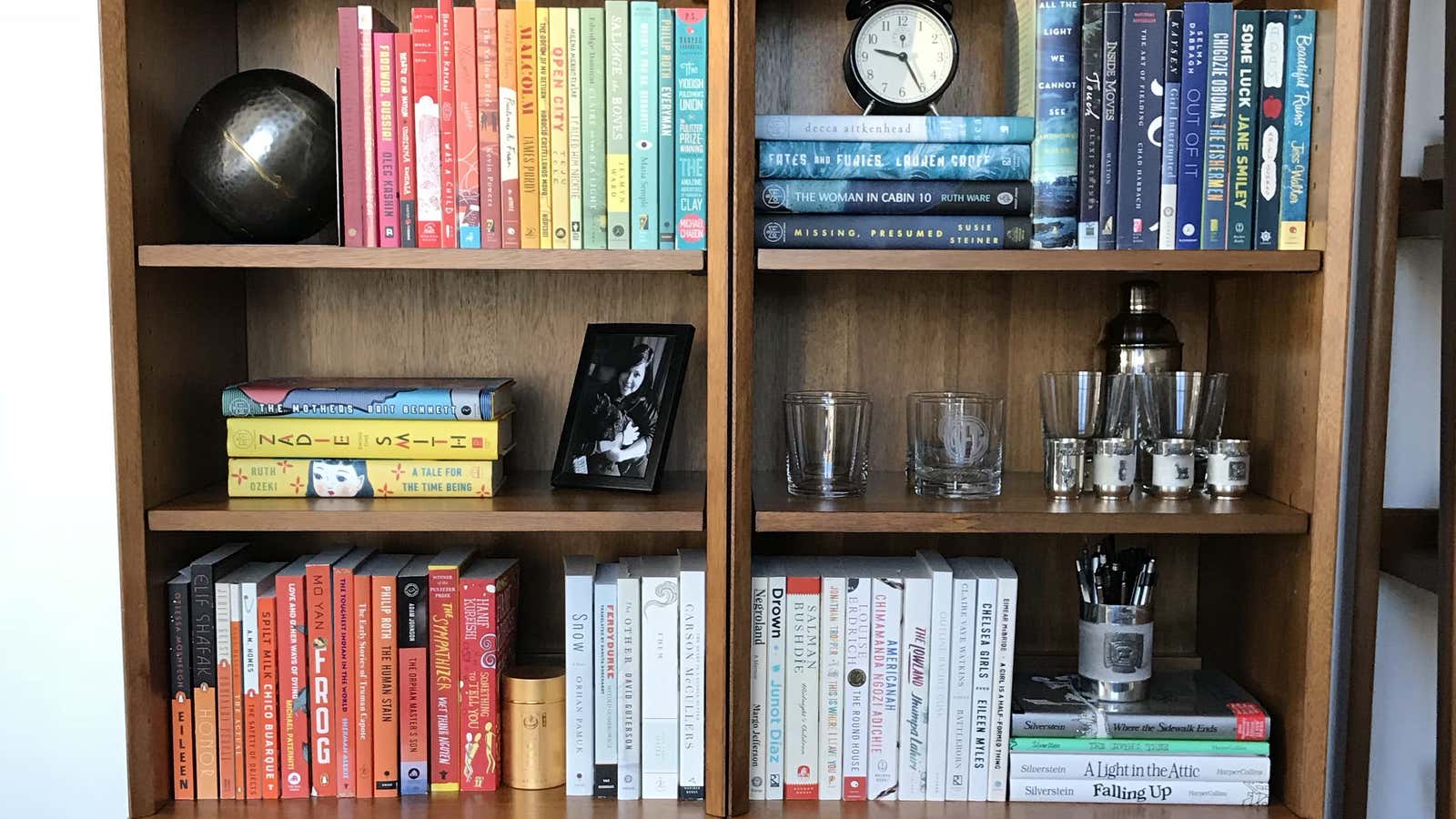

Color-coded

Some, including at least one Quartz editor, swear that they remember best where a book is by its look—that the book’s cover jogs the memory (“the blue one!”). But organizing books by color and spine height is often derided because it seems to rate books by their external features, rather than their contents.

Books as decor

Some people invite further scorn from purists by treating books like objects, using them to prop up furniture or as ornamentation.

Intention-based

Several people surveyed said they organize their books by their intentions or feelings toward them. A friend, a producer for a digital agency, wrote to me about how she stacks the books crammed into her tiny New York apartment:

– under my bed: books that I read and thought were good but not re-readable

– in my walk-in-closet: books I love and reread and I want near me so I can go back to them when I need a friend

– stacked on my floor: book(s) that I’m in the process of reading, or want to read next

– outside on the curb: that one book I regret purchasing and disliked so strongly that the mere presence of it in my apartment diminished the value of all my other books

One colleague says she keeps her unread books on the shelves toward the bottom, and the upper shelves are for books to be read.

By desire

The Norweigian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard tells the New York Times (paywall) his overall sorting method is chaos, but for books he wants to read, he divides them by his motivations. He describes them as id, ego, and superego piles: “On the floor by my bed there are heaps of books I want to read, books I have to read and books I believe I need to read.”

One Quartz video journalist says she sorts by “level of trashiness,” with “trashy” books near the bottom and more edifying literature toward the top.

Shelf dinner party

One colleague said she used to enjoy juxtaposing books whose authors would like each other, or whose ideas could create an interesting dialog. Jane Austen next to Adrienne Rich, for example. She admits she doesn’t have time for such a system now, and anyhow it’s not particularly practical. ”I didn’t always remember my own logic, so the purpose was not really to help me find books,” she says, “But more that the activity was pleasing in itself.”

Topic

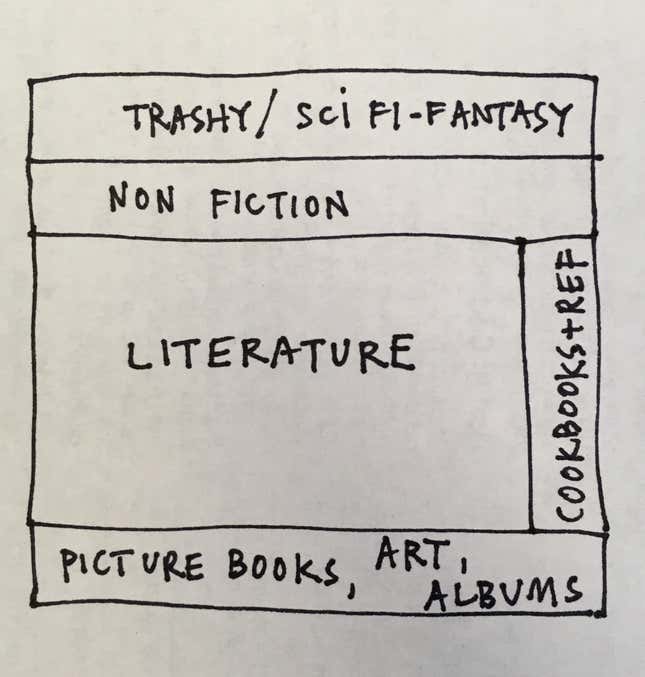

The method that came up most was organizing by genre or topic. Classic divisions might be: Non-fiction, fiction, anthologies, cookbooks. But they need not be so prosaic. One friend said her categories were: Viruses, types of philosophy, dystopian fiction, and non-dystopian fiction.

My sister, an architect, designed and built her own shelves at home, putting the heaviest on the bottom (art books, for example), literature at eye level, and the lightest at the top (sci-fi, romance), with cookbooks on the side for easy reference.

By location

My own shelves are sorted by region (the setting of the book, not the birthplace of the author). I took a cue from McNally Jackson, a bookstore in downtown Manhattan, whose fiction section is sorted by author’s region.

The system starts with Joan Didion’s Californian White Album on the bottom left, crosses the US to John McPhee sitting in New Jersey and Colson Whitehead and Teju Cole wandering around New York, and then goes roughly east across the world, ending in Duong Thu Huong’s Paradise of the Blind and Yaunari Kawabata’s Snow Country. There’s one section for transatlantic and fictional lands—putting Henry James’s The Ambassadors and Game of Thrones books together.

Internal logic within sections

One colleague reports sorting by topic, and then by his reaction to the books within each topic. Novels, nonfiction, manga, and plays are placed separately. “And then within those groups I arrange by how much I liked the book, left to right, with the rightmost books being unread,” he says. Another friend sorts the books overall by topic and then by color with each category.

Don’t even keep books

The editor for this story said she doesn’t even really like to keep books: If she likes something, she’s more likely to give it away, leaving behind books she hasn’t read or didn’t like.

Utter chaos

Quite a few advocated strongly for no system at all. “I like hunting for a book I’m sure I have without knowing where it is,” wrote a colleague’s partner. “It’s like browsing through a used book shop.”

Says another colleague of his system: “What’s it called when you have tons of boxes in storage and just swear the one with the green mark on the left side has the book you’re looking for… if you could only remember the reference point for the ‘left side’?”