An artist is destroying a signed Rauschenberg—to save art

Artist-designer Nikolas Bentel is destroying an original work by icon Robert Rauschenberg—and he wants you to help him do it. This seemingly reckless stunt is a deliberate and multi-pronged critique against the commodification of culture.

Artist-designer Nikolas Bentel is destroying an original work by icon Robert Rauschenberg—and he wants you to help him do it. This seemingly reckless stunt is a deliberate and multi-pronged critique against the commodification of culture.

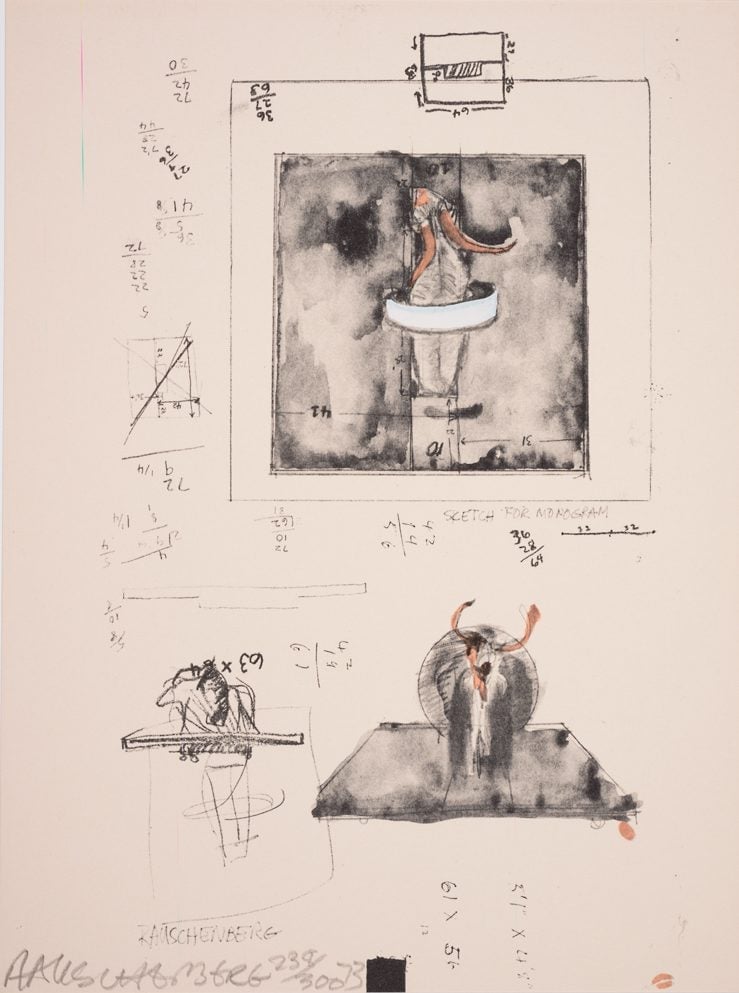

A forefather of the pop art movement, Rauschenberg was an “irrepressibly prolific” American artist who left a legacy of inventive mash-ups of ideas, materials, and artistic genres when he passed away in 2008, at age 82. Several Rauschenberg pieces have been sold for millions at auctions. His 1963 silkscreen titled Overdrive set a record when it sold for $14 million in 2008 at Sotheby’s.

It’s these art market fluctuations that has stirred Bentel. “Over the past few years, the art market has become way more interested in the monetary value of famous art pieces rather than their cultural importance,” argues Bentel who is a resident at the New Museum’s design incubator program. He cites the recent record-breaking sale of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, as the apex of its lunacy. In a dramatic 19-minute bidding war in New York City last November, Saudi Arabian prince Badr bin Abdulla paid $450,312,500 for the oil painting, despite its disputed provenance.

Never mind that the trippy, 1490 portrait of Jesus Christ was repainted several times over, or that some scholars doubt if it was actually painted by the Renaissance genius. Christie’s marketing blitz assured the auction’s success, convincing buyers that the painting that was sold for $59 just six decades ago is now worth hundreds of millions. “My project is here to point out this problem by having the art world perform arbitrage on itself,” says Bentel.

Arbitrage is a stock trading tactic where an investor buys stocks from one market and simultaneously sells sells in another, in the hope of avoiding risk and profiting from slight price differences. In Bentel’s provocation, one stock is equivalent to one square inch of advertising space that he’s selling for $92.59 apiece. The 108 inch-sized ad blocks will eventually cover over the 9 x 12-inch surface of a signed print of Sketch for Monogram, which Bentel is trying to procure for $10,000. (Conceivably, he can kick in the 28-cent shortfall.) Erasing Rauschenberg is art protest in the era of crowdfunding.

Bentel says he’s optimistic that he’ll sell enough blocks to reach his goal, and tells Hyperallergic that someone even bought six adjacent units to plaster a phallus over Rauschenberg’s print. As of this writing, there are 92 spaces left.

Bentel, who has previously attempted a “data arbitrage,” explains that he chose to deface a work by Rauschenberg because he admires him. ”[Rauschenberg] is someone who really broke away from what the art world really was—and he did this until he became the status quo,” says Bentel. “But it is now time to again point out the absurdities of the art world and break away from them once more.”

The project’s concept is actually lifted from Rauschenberg’s own conceit called “Erased de Kooning Drawing.” In 1953, the pop art bricoleur spent two months rubbing out a drawing by the revered abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning and exhibited the blank piece of paper two years later.

Destroying a work of art sounds like an extremist’s maneuver and counter to the valiant preservation efforts to rescue the world’s cultural treasures. Bentel justifies his project through its intellectual premise and awareness-raising mission.”I would never destroy an art piece that did not have any conceptual ties to the destruction process—that is just plain destruction. Rauschenberg’s work is perfect for this art piece since he was in the exact same position that I was in, when he erased the De Kooning art piece,” he explains to Quartz.

Despite his reverence for Rauschenberg, is Bentel only beginning in his art-destruction-as-protest campaign? Would he, given the chance, destroy Da Vinci’s $450 million auction sensation? “Leonardo had little to do with the painting that we see today,” he says. “So yes, I would have loved to destroy the Salvator Mundi.”