Internet fandom is running Hollywood

How would you react if the creators of your favorite TV series offer to just tell you everything that will happen on the show?

How would you react if the creators of your favorite TV series offer to just tell you everything that will happen on the show?

Fans of Westworld were faced with that question this week when showrunners Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy went on the HBO show’s Reddit page and made a bizarre proposition. If their post received a certain number of votes, they said, then they’d spoil the entire upcoming second season of the robot western, with a video laying out its plot points.

The offer turned out to be a stunt: a “Rickroll” joke followed by 22 minutes of a dog sitting at a piano. But the Westworld Reddit community didn’t know that at, and was predictably roiled up by Nolan and Joy’s modest proposal. In the hours after they posted it, the Reddit page filled with earnest debate over whether TV creators should spoil their own storylines, and much pontificating about the solemn responsibility of the fan community to determine whether or not they would.

Nolan and Joy haven’t said whether they intended to make some broader point about TV fandom or spoiler culture. It’s highly possible that the whole thing was simply a marketing stunt to stir the pot two weeks before the show returned from hiatus. But intentional or not, this odd Westworld affair revealed something deeply, dangerously true about modern entertainment.

Fans control it all. The inmates are running the asylum.

The term “fan service” has a long and fascinating history, but today it’s commonly used to refer to anything in entertainment that’s made specifically to please people who are already fans of that thing. A throwaway character’s death turns her into an internet meme and prompts a disproportionately large storyline in season two? Fan service. A movie is reshot to make it more like its well-received trailer? Definitely fan service. The entire concept of these Harry Potter prequel films? You already know.

But how did it get to be this way? How did Hollywood creators and executives become so beholden to the whims of their loudest fans? And why now?

A brief history of fan service

Of course there’s nothing inherently wrong with the idea of entertainers doing things to please people. Being entertained is the point of entertainment, after all.

That’s different from fan service, which is a far more cynical type of appeasement with some dubious origins. The term came out of Japanese anime and manga as a way to describe gratuitous sexual content that was overwhelmingly aimed at pleasing straight male fans. “Fan service” originally meant wish fulfillment—an attempt to literally “service” certain kinds of fans’ fantasies, sexual or otherwise. (Of course it’s not limited to narrative storytelling; one need only look to professional football or other sports leagues to see how catering to the basest impulses has become the rule.)

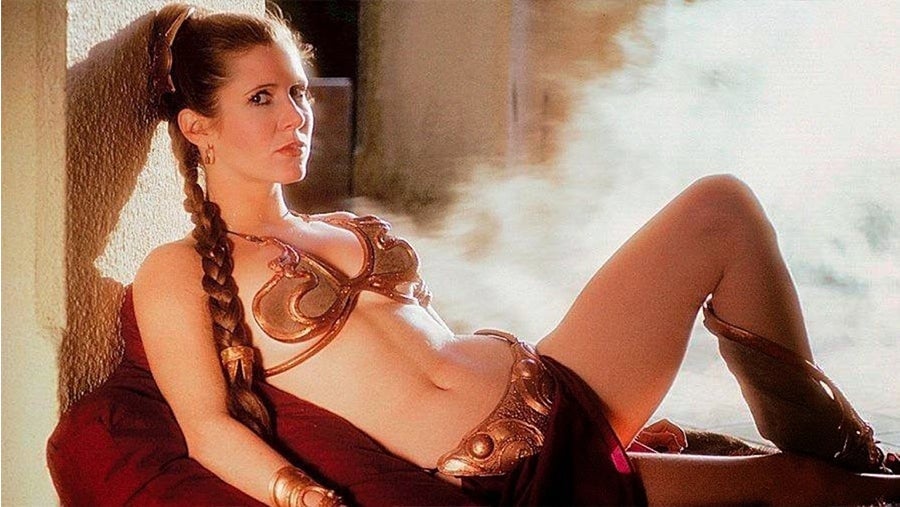

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, “fan service” had made its way into Hollywood. Pointless nudity was becoming more and more common, as were entire story lines that served no narrative purpose apart from titillating fans (again, usually straight male ones). The most notorious example is probably “slave Leia” in 1983’s Return of the Jedi—where Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) donned a metal bikini as a captive of the phallic, slug-like space gangster, Jabba the Hutt. It’s an episode that haunted Fisher for the rest of her career.

While this kind of gratuitous content is obviously still a huge part of modern entertainment, the term “fan service” has since evolved to have a much broader meaning. Now, it encompasses essentially any kind of creative pandering to, or indulging of, the impulses of a fan collective.

2017: the year fan service went haywire

Television and film are more indebted to fans than they have ever been. The Hollywood box office is on extraordinarily shaky ground, as streaming upstarts disrupt the system and studio executives scramble to find ways to put more butts in movie theater seats. One thing they know how to do is make sequels (and prequels and spinoffs and remakes and reboots) of popular franchises—themselves a form of fan service. But even that method has proven unreliable lately. Fans think they want more of what they already love, but it turns out that they sometimes don’t actually want that, much to the chagrin of studio heads trying to turn a reliable profit.

TV, meanwhile, has transformed into a medium wholly reliant on fan engagement in the age of streaming and social media. Ratings still matter (for broadcast and cable networks), but they matter considerably less than they did 20 years ago. Audiences have eroded for more than a decade, forcing broadcasters into diversifying their revenue streams. Most of the biggest networks, including NBC and CBS, have divulged that less than half their total revenue comes from ads. Networks are thus less beholden to those advertisers—and more to fans, cultural taste-makers, think-piece writers (hello!), and anyone else who might help create an aura of buzz or prestige around a show.

HBO generally cares a lot more about awards (and being the subject of your office water cooler discussion) than it does traditional TV ratings. Netflix and Amazon don’t particularly care about a show’s ratings—they refuse to even tell us how many people watch their shows and movies. They just want subscribers. So they make shows that their executives (or algorithms) think will motivate people to subscribe. For Netflix, that has meant creating a niche for every type of viewer imaginable. Recently for Amazon, that’s meant desperately trying to make the next Game of Thrones, assuming such a thing exists.

And, boy, are the fans eager to have their voices acknowledged. Social media has closed the gap between cultural producers and consumers. Aware of this newfound power, fans have become more demanding, more critical, and, most of all, more entitled.

For the fans, or for the critics?

By 2017, creators were pushing back against bad reviews by self-righteously asserting that they were making content specifically for fans, and not for critics. Huffington Post summed up many of the examples last summer:

Alex Kurtzman, who responded to negative reception of “The Mummy” by saying, “We made a film for audiences, not critics.” Or David Ayer, the “Suicide Squad” maestro who expressed his disregard in a tweet: “Made it for the fans.” And while “Batman v Superman” director Zack Snyder reacted to pans with an even-keeled “it is what it is,” his cast went further. “None of us are making the movies for the critics,” Amy Adams said. “What is really going to matter, I believe, is what the audience says,” Henry Cavill retorted.

And then there was Netflix’s Bright. The fantasy crime film was ruthlessly panned by critics, garnering a woeful 26% on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes.

Netflix executives didn’t mind, because the film was still its most-watched original piece of content (be it a film, show, or documentary) in the streamer’s history. CEO Reed Hastings dismissed critics as “disconnected” from mass audiences. Chief content officer Ted Sarandos conceded that critics were “an important part of the artistic process,” but clearly not as important as those in control of the commercial prospects of a film—the audience.

Bright was a resounding win for mass appeal. Despite the critical slaughter, Netflix announced it was making a sequel to the film with the same director. Ultimately, it shouldn’t have been that surprising. Of course a streaming service that monitors what people watch and uses mysterious algorithms to create more things like those other things is going to greenlight a sequel to something fans liked. That was the easiest decision the algorithms ever made.

The film that broke fandom’s rules

For 11 months, it was looking like 2017 would be a year in which culture became entirely fan-dominated, until Rian Johnson’s The Last Jedi came along. Sure, the fact that we’re still getting Star Wars movies means the fans won a long time ago—but Johnson’s installment was anything but fan-friendly. He crafted an original story that went very far astray of fan’s expectations, especially for the character arc of Luke Skywalker. Johnson told his tale, rabid fans be damned. And many of them weren’t happy about what this interloper did to their beloved Jedi master.

The Last Jedi was arguably a subtle commentary on fandom itself and how most stories are too obsessed with pleasing certain people at the expense of creativity and risk-taking. But the fan reaction to the film only underscored how entitled they believed they were to the direction of the story. The Last Jedi was a weird outlier in a year when the most popular TV and film franchises not only clearly aimed to please a certain subsection of vocal fans, but frequently felt as though they were written and produced by them too.

Who is art really for?

The Last Jedi kerfuffle publicized a question that gets deep at the heart of the fan service phenomenon: To whom does art belong? Is it narcissistic for an audience to expect some degree of influence over their entertainment? Is filmed entertainment democratic? Does it belong to everyone who watches it?

The internet has made fans’ voices loud, immediate, and ubiquitous, perhaps leading many of them to believe they wield more power than they really do. A byproduct of that show of power is that Hollywood has bought into it to a point where it’s become real.

What may have started as a mere guise of influence has clearly turned into a real cultural authority. Maybe a democratic approach to art doesn’t result in good art. Maybe it doesn’t result in art at all, but rather something far easier to make and much less challenging to contemplate.

All the ways Hollywood panders to fans

The website TV Tropes, a wiki devoted to the tropes and storytelling habits of TV, is an incredible resource for anyone interested in themes, clichés, and plot devices in modern media and entertainment. Among the boundless fascinating nuggets of trivia that TV Tropes contains are pages devoted entirely to providing examples of various kinds of fan service.

Here are just a few, excerpted from TV Tropes, with an example of how each type has shown up in Hollywood recently:

“Pandering to the Base“

Generally speaking, the more intensely devoted fans in a fandom are usually outnumbered by the casual fans, but the more devoted a fan becomes, the more active (and louder) they become in the fandom. So while a few million casual fans might enjoy an episode without ever making it widely known, a handful of devoted and occasionally unhinged fans are screaming on a web forum about how the show is now Ruined FOREVER, which can be seen and heard by everyone…including the people making the show.

The producers may then start pandering to these voices exclusively, believing them to be the voice of everyone watching (which they will often claim to be) — but “everyone” in this case may in fact consist only of a handful of people, and what this minority wants and what the other, less noisy fans want can differ drastically.

Example: Thor: The Dark World was allegedly rewritten and new scenes were filmed to place a greater focus on the villain Loki, due to his warm reception from the first Thor movie (Actor Tom Hiddleston becoming a Tumblr obsession probably had something to do with it too.)

“Fan Dumb“

A good fandom is successful by having a diverse community of people who share a mutual interest in the shared object of the fandom, but nevertheless remain mature and sensible enough to tolerate and respect differences of opinion. Most people in fandoms are actually like this.

Then there’s Fan Dumb. Fan Dumb is the underbelly, where Serious Business becomes obsession. They are the fans who claim to be the watchdogs of their fandom, but in reality, they’re the dog in the manger.The key characteristics of a Fan Dumb tend to be someone with an overdeveloped sense of entitlement and/or victimization, and (usually) an underdeveloped sense of humor or perspective about the subject of their fandom, coupled with an obsessive level of an interest and (frequently) some rather irrational views on the whole thing.

Finally, we can also mix this with the inability to distinguish fact from opinion and/or disagreement from hatred that so many people on the internet seem to be suffering from these days (despite these lessons typically being instilled in kindergarten). They usually believe that the very fact that they are a fan of something somehow entitles them to special or exclusive treatment, or that they are being persecuted by numerous different parties (the creator, the producers, other fans, the world at large, etc.) because of their fandom.

Example: The aforementioned The Last Jedi fiasco, but also the Rick and Morty fandom, which devolved into a toxic community that attributed a perceived decline in the show’s quality to the hiring of women writers.

“Why Fandom Can’t Have Nice Things“

This is when someone who is involved in the production of a work and is known for interacting with the fans by, for example, writing a production blog or answering fandom’s questions, or regularly appearing at conventions, stops doing so because, at least in their opinion, some fans become so thick and heavy (and ugly) that their previously fun activity has become a burden and is no longer enjoyable.

Example: Lost co-creator and showrunner Damon Lindelof, one of the most transparent and accessible creatives in Hollywood, deleted his Twitter in 2013 in part due to incessant vitriol he received from internet tough guys.

“Ascended Meme“

Sometimes a meme about a work, that wasn’t in the work before, catches the eye of the people responsible for that work, and they decide to actually put it in the work.

Example: Game of Thrones acknowledged a popular internet meme about the character Gendry. (He had last been seen on the show rowing away, so for years fans joked that for all they knew, the character was “still rowing”—when he finally reappeared on the show, another character made that exact joke about his sudden return.)

“Ascended Fanon“

This is when fanon is promoted to canonicity. Whether it’s officially shown in a canonical work is another matter, and may “only” reach the status of Word of God, but most of the time the author(s) sees some minutiae they hadn’t thought too much of themselves as a decent enough explanation that they don’t mind and don’t want to Joss it into oblivion.

This mainly happens when the theme or subject of the fanon had not been planned out by the author(s) beforehand, and is much more common in works, such as fanfiction and webcomics, which often aren’t planned from the start.

Example: In Game of Thrones, fans theorized that a mysterious character named Coldhands was in fact Benjen Stark in disguise. Despite the fact that George R.R. Martin—the author of the books on which the HBO series is based—denied that, sure enough, when Coldhands showed up on the TV series, it was Benjen Stark. (There are many other examples of “Ascended Fanon” on Thrones, including the term “warging.”

“Ensemble Darkhorse“

This trope is used to describe a side character making up part of the Ensemble, either a non-lead secondary character or a mere Flat Character, who then becomes unexpectedly popular with the fandom (sometimes, even more than the lead characters) depending on who and where the Fandom is, as well as what the other characters are like in comparison (for example, the hero is not as popular because they’re too much The Everyman). Often, this can happen because the character has very few character traits, allowing fans to imagine this character to have traits that they like.

The Ensemble Darkhorse can sometimes be viewed as the character equivalent of a Cult Classic.The writers or producers may be tempted to Retool the show’s premise to put themin the spotlight. Sometimes this works, but usually it’s a bad idea for two reasons, both relating to what happens when you take a supporting character and move him or her into The Protagonist‘s position. The first is that writers often “adjust” the character so that they can fit into a conventionally heroic role — in the process destroying the unconventional traits that made the character an Ensemble Dark Horse in the first place. The second is that if the writers don’t do this, traits that were entertaining in a secondary character may become grating and unpleasant in The Protagonist.

However, it’s still good business to bring Dark Horse characters back, even if they were originally meant to be featured for only a short time. Thus, episodes which do not specifically require a certain character will be more likely to use the Ensemble Dark Horse.

Example: Barb in Stranger Things; Hodor in Game of Thrones; lots and lots of people in Doctor Who; Agent Coulson in the Marvel Cinematic Universe

“Running the Asylum“

When a franchise expands into a Long Runner, themes, ideas, and interpretations will inevitably start being lifted from the fanbase. And when a fictional franchise has lasted long enough to induct its fandom into the ranks of its professional creators, the same devotion that produces Fan Fic will inevitably emerge in the “canon” material. Basically, the “inmates” take over the asylum.

Sometimes this leads to good things and produces some damned good stories, but other times, the same kinds of motivations and factors that lead to the creation of bad fanfic come into play, to the detriment of the series in general. Sometimes some editors are on hand to curb the worst of it, but other times, things just go Off the Rails.

Example: Avengers: Infinity War; Hollywood.