The Pritzker Prize finally recognizes the genius of Indian architecture

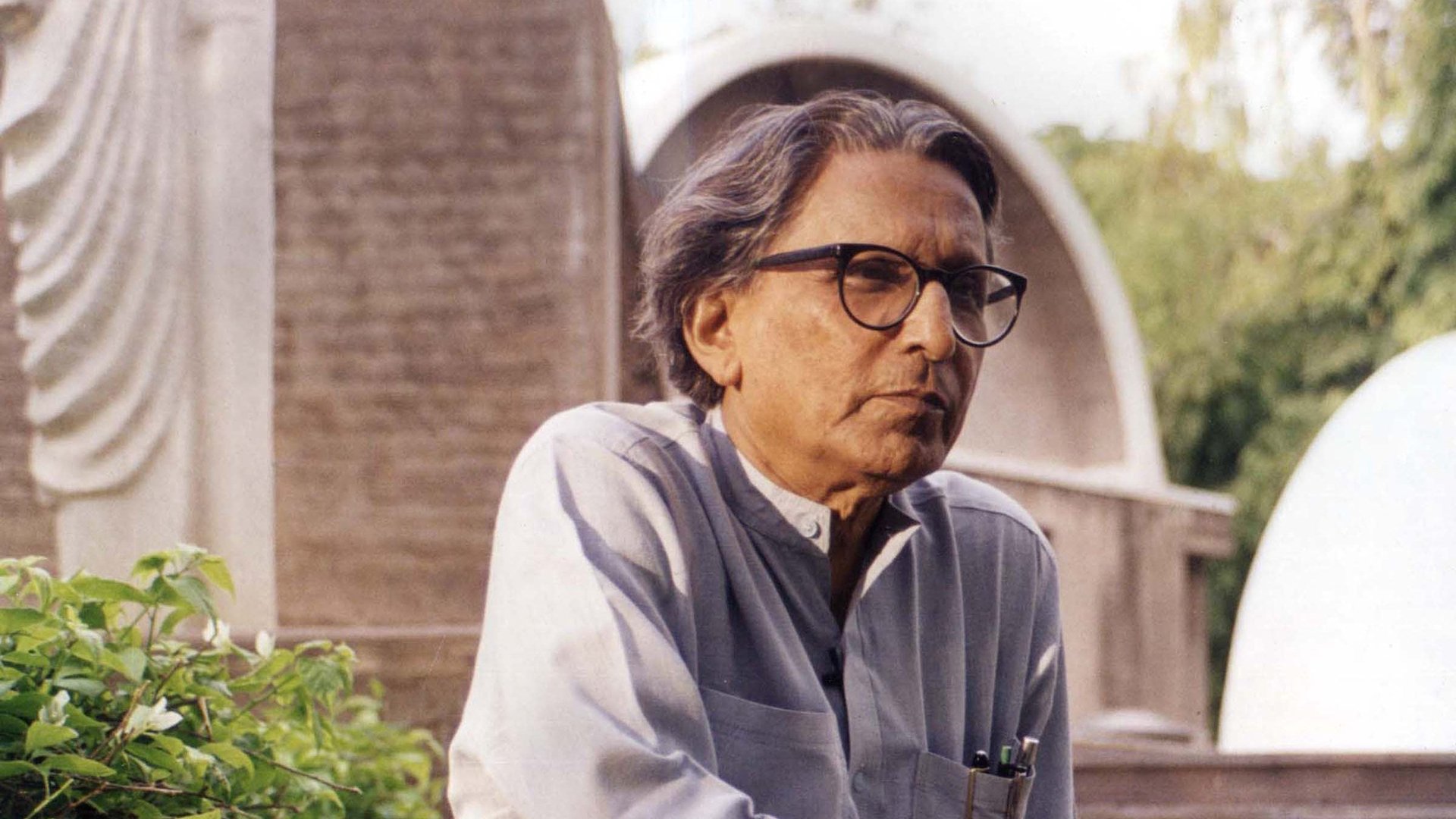

The gods of architecture have finally turned to India. Balkrishna Doshi, a 90-year old architect and academic is the recipient of this year’s Pritzker Architecture Prize. It’s the first in the so-called “Nobel prize of architecture’s” 40-year history that the Pritzker has been bestowed to a South Asian architect.

The gods of architecture have finally turned to India. Balkrishna Doshi, a 90-year old architect and academic is the recipient of this year’s Pritzker Architecture Prize. It’s the first in the so-called “Nobel prize of architecture’s” 40-year history that the Pritzker has been bestowed to a South Asian architect.

To globe-trotting architecture fans, Ahmedabad-based Doshi’s name might resonate as the steward of western architects’ Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn’s modernist vision in India. Working with the French-Swiss architect in Paris in the 1950’s, Doshi oversaw the construction of several buildings in Ahmedabad and Chandigarh, where Le Corbusier famously left his mark. In the 1960’s, he also worked with legendary modernist Kahn on the Indian Institute of Management’s building in Ahmedabad.

Doshi was a vital, though largely unheralded partner in creating India’s meccas for modern architecture. He translated Le Corbusier and Khan’s plans to Indian construction standards and found ways to weave pre-fab materials with artisan-made elements.

“A lot has been said and continues to be said about the shadow of Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn on the city and the country at large, but it was Doshi who grounded their ideas in the soil of India and turned them into something entirely new,” explains Avinash Rajagopal, editor-in-chief of Metropolis magazine.

Doshi has also been a teacher for most of his career and helped establish schools of design in Ahmedabad. He was the founding director of the School of Architecture and School of Planning there—and played a vital role in developing the renowned Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design.

He’s also an internationally-respected academic and a frequent lecturer in US and European universities. Doshi helped shape UNESCO-backed International Charter on the Education of Architects, which forged an international alliance of industry practitioners. He’s a fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Indian Institute of Architects and has honorary doctorates from the University of Pennsylvania and McGill University in Montreal.

A prize for India and beyond

Speaking to CNN, Doshi said he shares the prestigious honor with all of India— a nation whose impressive architecture legacy which has been largely overlooked by architecture elites. “I think it is very, very significant that this award has come to India—of course to me, but to India,” says Doshi. “The government, officials, those who take decisions, cities—everyone will start thinking that there is something called ‘good architecture.'”

Born in Pune to a family of furniture-makers, creating inspired public architecture has always been Doshi’s ambition. “It seems I should take an oath and remember it for my lifetime: to provide the lowest class with the proper dwelling,” he said in 1954, when he was just starting his career. He tackled several low-cost housing projects at Indore and Ahmedabad, imbuing them with a sympathy for how communities lived and thrived in resource-poor areas.

A highlight in his portfolio is the Aranya Community Housing in Indore. Built for 80,000 residents, Doshi designed 80 model homes and a labyrinth of pleasing courtyards and pathways throughout the 85 hectares site. The project garnered the Aga Khan Foundation architecture prize in 1995, with the judges applauding the designers’ “effort to integrate families within a range of poor-to-modest incomes.”

“Places like India represent for the world the importance of the roles of architecture and planning for basic needs and for improving the basic human condition,” says Rahul Mehrotra professor of urban design and planning at Harvard University. He explains that India offers a terrain for designers to get involved in addressing key global challenges such as urban density, housing, and study how traditional societies adapt to globalization.

Doshi’s Pritzker, Mehrotra suggests, is also a call for young Indian architects and designers to be—like Doshi himself—more engaged with the often gnarly occupation of city-building.”In India, the priority is for architects to engage in these rather wicked problems,” Mehrotra says.

“I believe that most architects are preoccupied with what I call ‘the architecture of indulgence.’ These are homes for rich people, museums, things of luxury and consumption. I think recognizing Doshi’s work and recognizing India could help that message come across to architects,” he says. “Because finally, architects as a profession, will be judged by the questions and issues we spend our time on and focus our energy! “

Doshi will collect his $100,000 prize from the Hyatt Foundation, which sponsors the Pritzker, in a ceremony in Toronto, Canada later this month. Following Chilean architect’s Alejandro Aravena’s laureate in 2016, and the Catalan trio of RCR Arquitectes last year, Doshi’s selection signals the Pritzer’s growing appreciation for relatively unknown architects working in social change projects in their regions.