In 1921, Queen Mary (the grandmother of Queen Elizabeth II) received as a gift an elaborate house that showcased art and modern technological advancements. It was just 3 feet tall.

The dollhouse was built on a 1:12 scale. To fill the intricate home, the queen asked some of the big literary names of the time—Arthur Conan Doyle, Thomas Hardy, and Joseph Conrad, among others—to write original stories that would be kept as miniature books in the dollhouse library.

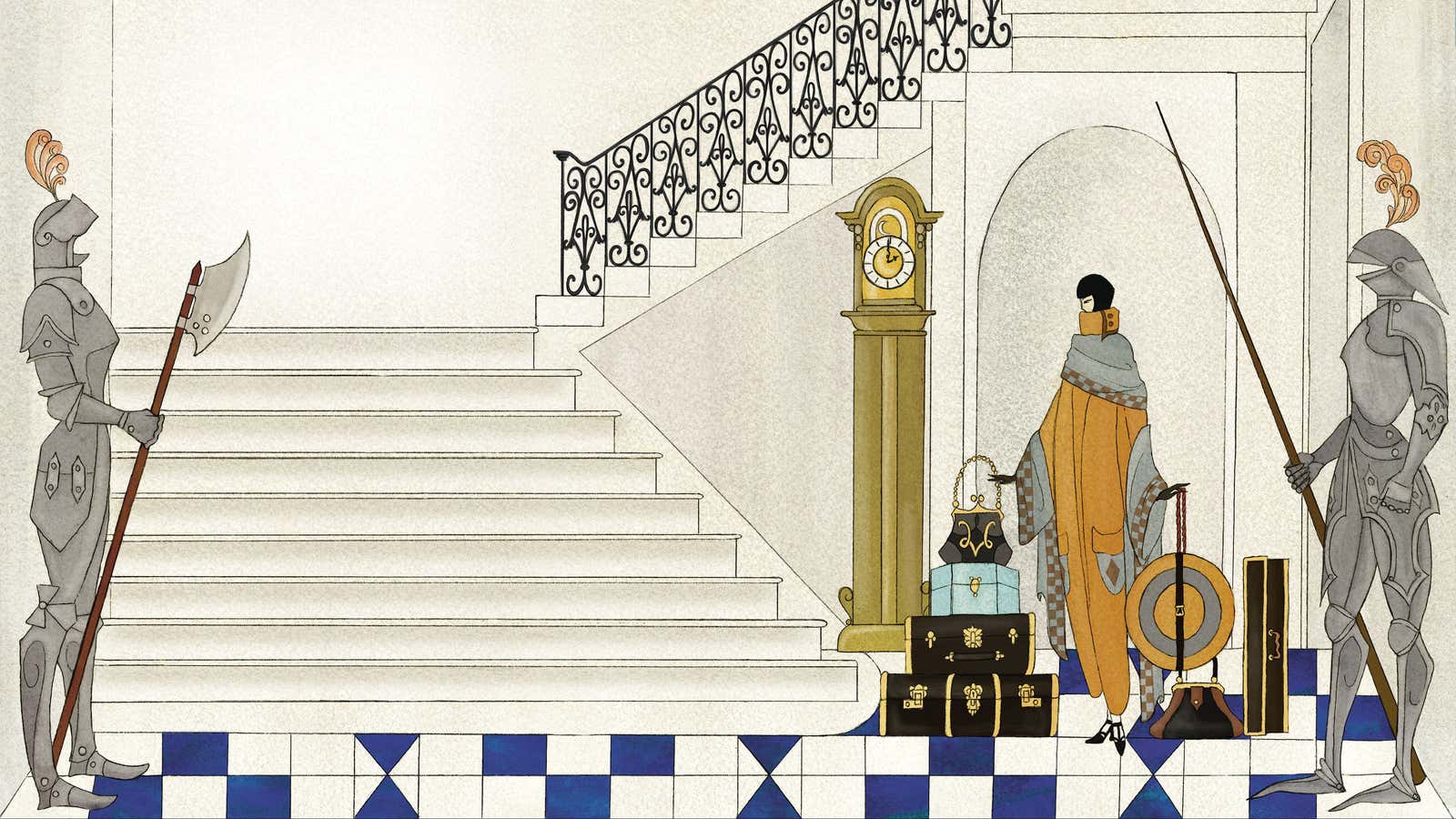

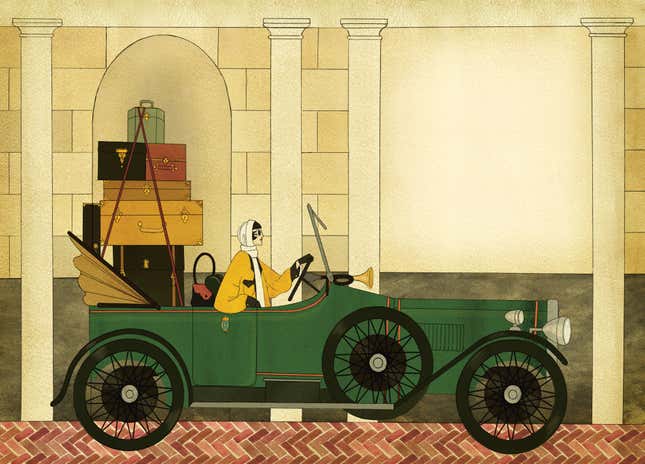

A postage-stamp-sized book by the writer Vita Sackville-West, best known as the inspiration for Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando, was made public as a book for regular sized hands for the first time last year. A Note of Explanation, with illustrations by Kate Baylay, was released this week in the US, from Chronicle Books.

Sackville-West has herself been the object of fascination: Both a reserved English aristocrat and a fierce and flamboyant fantasist, who was married to a man but had a long list of romances with women, including Virginia Woolf. A Note of Explanation is about a chic spirit who lives inside a tiny dollhouse. The spirit has lived through generations of fairy tales, seeing Cinderella leave for her ball, for example, and a prince kiss Sleepy Beauty—not unlike Woolf’s Orlando, who embodies multitudes of identities and genders, and who lives over three centuries.

In the afterword to the story, Sackville-West’s biographer, Matthew Dennison, writes of how she lived through her fiction. “Dramatic self-inventions were her literary stock-in-trade: Fictional heroines whose dilemmas mirrored her own; heroes who achieved the outcomes to which Vita aspired,” he writes. “But from which she felt herself excluded on account of her gender—the inheritance of a great aristocratic house and title and the love of a beautiful woman.”

In her story Sackville-West wrote of the spirit protagonist, “She found herself greatly delighted by the brilliant jerseys and short skirts with which she provided herself for daytime wear, and by her own dark little clubbed head, which gave her a boyish, page-like appearance unfamiliar to her since the ten days she had once spent in listening to the stories of Boccaccio and his friends in a villa above Florence, way back (this was one of her new expressions) in the fourteenth century.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story said that Queen Margaret commissioned the construction of the doll house; in fact, it was Queen Mary, and she received it as a gift.