In the famous 1967 poem “Postlude/Home,” the Barbadian poet Edward Kamau Brathwaite asks:

Where, then, is the nigger’s

home?

In Paris Brixton Kingston

Rome?

Here?

Or in Heaven?

That same burning question—of a black man’s place in the world—is the driving force behind Being Blacker, a new documentary by acclaimed filmmaker Molly Dineen.

The documentary centers on Blacker Dread (real name Steve Burnett-Martin), a Jamaican-born reggae producer, businessman, and community pillar. Dineen first met Blacker in 1981, when she was a student filming a documentary about reggae sound culture. When she bumped into Blacker again, nearly 40 years later, he asked her to film his mother’s funeral. The series of dramatic events that followed kept the camera rolling for the next three years.

At the center of the film is Blacker’s search for home: Is it in St. Thomas, Jamaica, where he was born, or Brixton, South London, where he grew up? While following Blacker on this personal journey, Dineen weaves a powerful story about life in contemporary Britain for the black community—revealing both the joyful bonds that people like Blacker can forge, and the ways those bonds are ultimately weakened by structural forces of racism and gentrification.

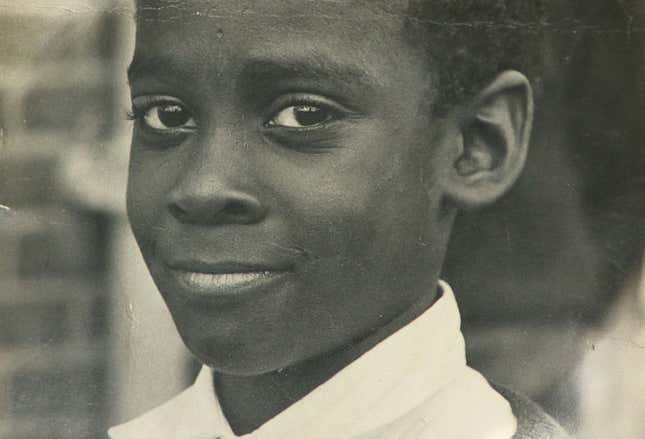

Blacker migrated to London when he was just nine years old. London in the 1970s and 1980s wasn’t an easy place to be growing up as a young black boy. The far right often roamed the street, while rising tension around police racism, high unemployment, and poor housing and education culminated in the 1981 Brixton riots.

Violent clashes by young black men and the police shocked the nation, but they pointed to an uncomfortable truth. The rest of the country had imagined that black immigrants from the Caribbean and Africa were not only well-integrated, but had access to the same opportunities as their white counterparts. The riots and explosion of racial tension shredded the myth that Britain was living in a post-racial society.

That same racial tension and deprivation plagued Blacker’s life. When he arrived to the UK, Blacker did well on his school entrance exams. The teachers were convinced his high score was a mistake, and asked him to take the test again. He was mercilessly bullied at school for being black. When, as a teenager, he sold programs at soccer matches, fans would shout “Oi nigger, come sell me a program” or call him a “black cunt.” He remembers people telling him to “go up on the jam jar, you little gollywog.”

Despite this torrent of racist abuse, Blacker was able to thrive. That was largely thanks to the community he had built in Brixton. Blacker became well-known during the rise of reggae sound culture; the documentary captures intimate shots of Blacker giving advice to the young and making cheeky jokes with the old. He also brought plenty of music, laughter, and dancing to his shop, the Blacker Dread Music Store, which was an important anchor to the black community in Brixton for over two decades. The music shop was a popular hang-out spot both for young black youth interested in reggae culture, and for older members of the community looking to jam and reminisce. Places like this—where young people are not only welcomed, but permitted to hang out in a warm, communal space free of charge—remain rare in London.

That makes it all the more heartbreaking when the shop closes down. As family and friends dismantle his shop, Blacker admits to Dineen that he’s been found guilty of money laundering and is being sent to prison. A local resident stops by and is devastated to see the shop is closing. She asks: “What can we do?” The answer, unfortunately, is nothing. The community Blacker helped build from the ground up is slowly withering away.

In the end, the tight-knit community couldn’t withstand London’s fast-changing socioeconomic climate. While people like Blacker helped make London the city it is today, gentrification is slowly pushing low-income families and people of color from iconic spots in the city.

It’s here that the documentary really comes into its own. Dineen brilliantly explores the tension and gaps in opportunities between first- and second-generation immigrants. African and Caribbean migrants who moved en masse to the UK in the 1950s were told if their children worked hard, they’d reach the top. But their children quickly learned that no amount of hard work would allow them to break through structural barriers to success. Their grandchildren and great-grandchildren are reckoning with those same lessons today.

The documentary also doesn’t shy away from the fact that black youth in London are badly affected by gang violence. The situation has become critical; London’s air ambulances today are more likely to be sent to respond to a stabbing or shooting than a traffic collision. Blacker believes the violence can be traced back to failures of the education system as well as a crisis of black identity. One older black man tells Dineen, “The youth don’t know anything about Africa or the West Indies.” Blacker takes Dineen to a vigil of a child killed by another child outside a school. During the vigil, a school friend of the deceased makes a passionate speech for unity: “Other cultures can be together. But we’d rather fight people and go and stab and shoot people. And it’s for what?”

To stop his youngest son, nicknamed JJ, meeting the same fate, Blacker sends him to Jamaica to finish his schooling. In England, JJ was told he didn’t belong in mainstream school; that he probably had ADHD and autism. He was seen as yet another unruly black child, and was sent home from school on a weekly occurrence.

In Jamaica, Dineen finds JJ excelling at school. He’s an A student who completed the year in the top of his class. JJ speaks of his Jamaican teachers’ high expectations of him, and most importantly, how he now feels “normal”—a subtle, but stunning, rebuke of the education system he left behind.

On the day of his sentencing, the judge deems Blacker to be “a failure.” The label stands in stark contrast to the words that members of the community use to describe Blacker, highlighting the enormous gap between the roles that black British people play in their communities, and how the system insists on seeing them.

After serving 15 months, Blacker is released from prison. Once he’s out, Blacker reflects on his life in the UK. He finds his store is now a boutique dress shop. Next door is a real-estate agent advertising houses that are out of reach for his family and friends.

When asked if much has changed for the black community since he was a teenager in the 1960s, Blacker somberly answers no. He points to his own family to illustrate that point. Issues of gang violence, poor access to decent education and job training, as well as few job opportunities continue to plague the black community today. Blacker’s eldest son, Solomon, was shot in the back of the head almost a decade ago. The police have yet to find his killer, or even offer an explanation as to why Solomon was killed. Blacker describes the death of his son as a “war wound”—one he’s never really healed from.

Ultimately, the documentary comes to a bitter conclusion: While Blacker has spent the vast majority of his life in Britain, it’s never made him feel at home. Toward the end of the film, Blacker brings flowers to his mother’s grave. She was the reason why he came to the UK. Now that she’s dead, he is ready to return to Jamaica. “Why would I want to stay here and suffer?” he asks.

The final scenes shows clips of Brixton on a snowy day. Garbage workers, who are all black, are seen clearing the street of rubbish. Blacker dances in the snow and sings: “England is pretty, but it’s cold.”