Last week Julia Turshen, author of Feed the Resistance, announced that she had created a database of women in food, with a focus on women of color and LGBTQ-identified folks, called Equity at the Table. But more than just creating a list Turshen has potentially upended the entire way that food stories are reported and panels at festivals and conferences are booked.

Equity at the Table is a tool that refocuses the narrative of food media and makes women more visible; it says that female chefs, sommeliers, and restaurant owners are interesting in their own right—and not just as the victims of badly behaved men.

While it’s unlikely that we’ve seen the end of sexual misconduct in the food world, Turshen is part of a wave of creative thinking that is changing the industry. An important part of this change is anchored in design—which women are using as a tool, not just to light dining rooms for Instagram, but making small changes to everyday elements in restaurants to reframe the way we think about working in food.

These fixes—whether they’re what is hanging on the wall in a break room or how service is run up front—are inverting a power dynamic that has in the past made harassment seem normal. And they’re doing so simply by being widespread, visible, and unchecked.

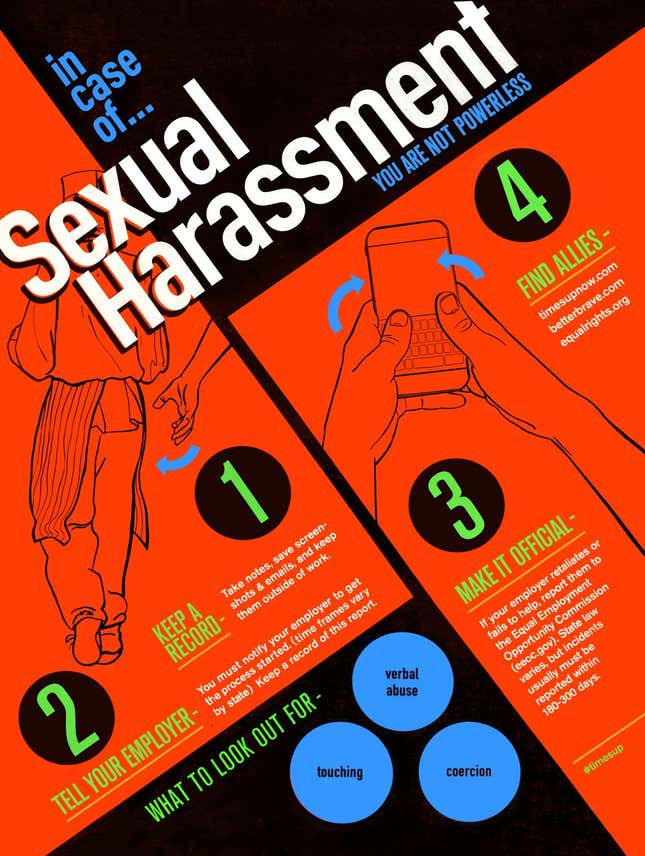

In San Francisco, Karen Leibowitz, co-founder of The Perennial, worked with female-focused foodie magazine Cherry Bombe and designer Kelli Anderson to create a poster that clearly illustrates what to do in the case of harassment. “I was at a dinner for women in the restaurant world in January, and we were all talking about sexual harassment, and I was thinking about how to move from outrage to problem solving and that’s how I came up with the poster idea,” she said in a Facebook chat (full disclosure, Leibowitz and I are friends from college).

Though much more attractive than your typical minimum wage poster, the power of Leibowitz’s design is that it makes reporting sexual harassment just as routine as any other piece of workplace bureaucracy. It normalizes action while underscoring that harassment should not be the norm. “When I talk about this issue with women restaurateurs in San Francisco, we always say to each other, why don’t these cooks and servers and bartenders come to us?” she said. “We just want to reach out and say, get out of that bad situation, and the poster was a way of doing that.”

Across the bay in Oakland, a restaurant called Homeroom redesigned the server experience by implementing a color coded system to report bad customer behavior (which tends to impact women the most). Servers can report a specific table or customer to a manager by simply by using a three-tiered labeling system, yellow, orange, or red. Each one triggers a pre-determined response, with no further explanation needed; in some cases the manager may take over the table, in extreme cases the customer may be asked to leave.

This way of designing service implicitly affirms that a server’s instincts are correct; and that an interaction that starts as a series of unwelcome comments is not allowed to escalate to the level of, say, unwanted touching. The default is no longer to make the person being harassed prove that something untoward is happening; it’s to believe that there is a problem from moment one—and offer an immediate solution.