There was a time when everyone knew Will Burtin’s name. The German graphic designer’s talents was so renowned that publishers, museums, and scientists clamored for his services. And so did fascist rulers.

As a young designer working in Cologne, Burtin impressed the Nazi propaganda minster Joseph Goebbels, who offered him the position of design director for the party’s hype machine. Adolf Hitler himself tried to get Burtin to design an exhibition about the rise of fascist culture in Europe.

Determined never to work for the Nazi party, Burtin escaped to the US with his first wife, Hilde Munkin, in 1938. There he established himself as a master of illuminating complex data. He dazzled clients with his ability to simplify complex procedures through accurate and beautiful information graphics.

During the war, Burtin worked with the CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services, where he created instructional manuals. He’s credited with helping US soldiers learn how to safely operate a gun through wordless diagrams. Knowing that most recruits couldn’t read, Burtin created simple drawings that shortened the training from six months to six weeks.

Bestowed with the industry’s highest accolades, Burtin should have been remembered along with other luminaries of mid-century design, but somehow his name has virtually disappeared from history books. Now, a new monograph about this “neglected giant of graphic design” seeks to remedy this omission and reintroduce Burtin to a new generation of design enthusiasts.

“I see his legacy in the ways that designers deal with the data explosion of recent years,” explains Adrian Shaughnessy, publisher of the forthcoming book, Will Burtin: Journey to Understanding. “As designers we have an almost sacred duty to help render this deluge comprehensible. And in this, we can ask for no greater model than Burtin.” Shaughnessy worked with the historian R. Roger Remington, the data visualization expert Sheila Pontis, and the celebrated graphic designer James Goggin on the stunning book.

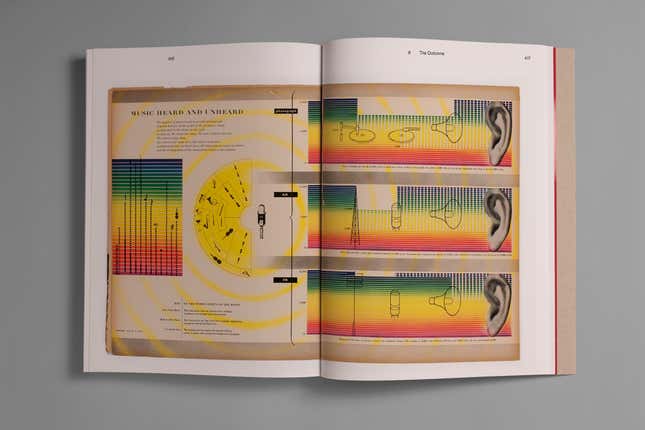

After a four-year stint as the art director of Fortune magazine, Burtin started his own design firm and worked on Scope, arguably the most beautiful biomedical journal ever circulated in the US. Working with a Michigan-based pharmaceutical manufacturer, the Upjohn Company (now owned by Pfizer), Burtin created richly-illustrated magazine spreads, making the dense scientific language inviting and understandable for the reader—all without the aid of the sophisticated data viz tools we have today.

Beyond the printed page, Burtin also designed captivating and popular multi-media exhibitions. The 1958 traveling exhibition he called “The Cell” drew 10 million visitors. “We take it for granted today that graphic designers can be multidisciplinary, but when Burtin did it, it was revolutionary,” says Shaughnessy.

Shaughnessy argues that Burtin’s work is especially worth studying today amid the immense technological and bureaucratic complexity that rule our lives. “I’d love to see him address the question of the internet, and how we handle information in the digital era,” says Shaughnessy. “His ability to turn technical details into accessible but always elegant visual material is as relevant today as it was in the sixties.”