Cudjo Lewis was a teenager when his home town in modern day Benin was decimated by a neighboring king. Lewis was captured, put into a barracoon, a structure to hold slaves, before spending 70 days crossing the Atlantic Ocean. He eventually arrived in Alabama, where he was given over to white masters. For all the horrors he saw in his lifetime—neighbors beheaded, people caged for two weeks while crossing the ocean, his son murdered by a cop—it is Lewis’s remarkably calm recounting of his story that makes his tale so affecting.

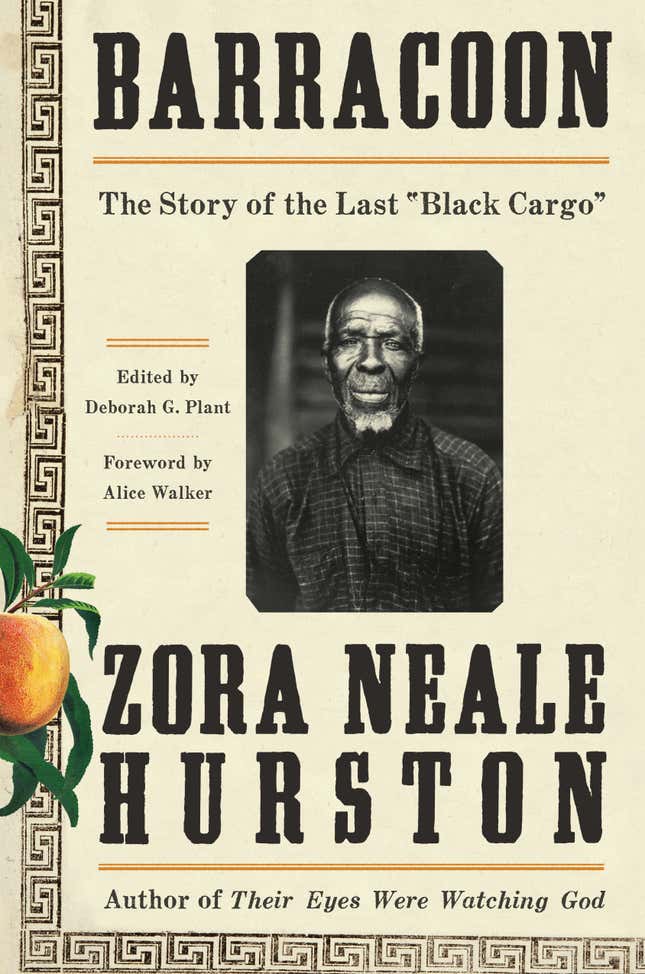

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” is an ethnographic account of Lewis’s life. Completed by Zora Neale Hurston in 1931, it was published for the first time on May 8 by Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins. The slim book is an intense and moving historical account of a life irreparably devastated by the American slave trade.

Based on a series of interviews with Lewis in the late 1920s, Barracoon is told almost entirely by Lewis, in his own vernacular. (In 1931, Viking offered to publish the book, but only if the dialog were converted to “language rather than dialect.” Hurston turned down the proposal.) Hurston appears, a forgotten voice-over, every few chapters, to remark on Lewis’s misty, far-away look, or to say he dismissed her for the day.

Lewis was born Oluale Kossula in the Yoruba town of Bantè, in west Africa, one of his father’s 13 children by three wives. At 19, Lewis was engaged and beginning the rites of manhood when nearby soldiers from Dahomey, under a war-mongering king, raided his town and slaughtered its people and king. Lewis was separated from his family and transported to the coast by the Dahomey forces. He eventually landed in Alabama in 1860 on Clotilda, the last known slave trade ship from Africa to the US. (The import of African people to the US as slaves had been outlawed in 1808, but the trade went on despite the ban.)

The five years and a half years Lewis was in slavery, before the end of the Civil War, is only one chapter in his story. His narrative is not one of cruel masters who rape their slaves or force them to dance for their amusement. The stronger thread is Lewis’s loss of home. At one point he begins to tell Hurston about his grandfather, and she interrupts him to say, “But Kossula, I want to hear about you and how you lived in Africa.” Lewis gives her a “look full of scornful pity,” and replies, “Where is de house where de mouse is de leader? In de Affica soil I cain tellee you ’bout de son before I tellee you ’bout de father.”

It’s not an easy read, for anyone. Lewis’s biggest antagonists in the US are black Americans who taunt him, his family, and other newly arrived Africans as “savages.” In her introduction to the book, Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple, refers to this record of atrocities by other African people: “One understands immediately the problem many black people, years ago, especially black intellectuals and political leaders, had with it.” “This is, make no mistake, a harrowing read,” she adds of this uneasiness, “We are being shown the wound.” Readers may be disturbed by passages in which Lewis describes one of his masters as a “good man,” who would replace Lewis’s beat-up shoes, and feed his slaves.

Without hate, rage, or resentment, Lewis recounts his losses: first his family and home in Africa, then the family he built in the US. In one chapter, he describes with woeful precision a laundry list of deaths: each of his children, to sickness, murder by a deputy sheriff, a train accident—then, suddenly, his wife. As he recalls one of his sons, Poe-lee, angrily trying to urge him to action after the death of another of Lewis’s sons, he says:

I astee him, ‘Whut for? We doan know de white folks law. Dey say dey doan pay you when dey hurtee you. De court say dey got to pay you de money. But dey ain’ done it.’ I very sad. Poe-lee very mad. He say de deputy kill his baby brother. Den de train kill David. He want to do something. But I ain’ hold no malice. De Bible say not.

This resigned sense of a life lost is reminiscent of stories told by refugees in the last century. But Lewis didn’t flee his home by any remote choice of his own, because of war, oppression, or economic loss, but of actual forced capture. He’s at once a pawn of a masterful act of capitalism, colonialism, inhumane oppression, and global power, and a formidable agent of change in his new town, where he bought land, built a church, built a school, and sued white company owners in court. But perhaps most important, almost 100 years later, is how Lewis’s clear, detailed memory of what happened to him has given a new dimension to America’s darkest moment.