Walking through my favorite local vintage shop the other day I spotted a thrifting Holy Grail—deadstock. Specifically two thick, cottony sleeveless mens undershirts with exactly the shorter length and thicker rib that I like for $1 each. Not quite sure what I’m trying to describe? They’re commonly called “wife beaters,” a term that came into heavy use about the same time my new-old-undershirts were likely made.

Though I plan on wearing the tops in heavy rotation this summer, I’m not going to be calling them that, even though it rolls off my tongue with ease. See, I’m part of the problem. There’s a mid-century feel to the usage, invoking images of Ralph Kramden and Stanley Kowalski, maybe Archie Bunker in his chair, but commonly referring to an inexpensive sleeveless undershirt as a “wife beater” only truly caught on during the ironic 90s culture I reveled in as a needlessly cynical teenager.

Saying it gave me the same frisson of toothless edginess that, say, referring to something less than optimal as “ghetto,” or drinking 40-ounce bottles of malt liquor with other privileged kids on my predominantly white college campus did. That is, until it just became a normal, unthinking thing to say. It’s a look that hasn’t aged well and isn’t cute in retrospect.

The New York Times ran a “can you believe what the kids are saying now?” piece about the “wife-beater” phenomenon back in 2001. In it, the writer describes a generational divide between deadpan young people carelessly tossing the term around and aghast olds attempting to provide some sort of appropriate lecture about feminism, the seriousness of domestic violence, and the power of language. By 2008, the term was in such widespread use that the New York Observer saw fit to include it in an article headline suggesting that then-senator Barack Obama was signaling his working class cred by clearly wearing one under his white dress shirt.

The Times revisited the issue this past weekend weekend, in an essay that highlights how the 90s-era nickname doesn’t just make light of violence against women, it also plays into stereotypes about the working class, immigrants, African Americans, and gay men—and it’s not the first article to do so. That is a lot of weight for a couple ounces of cotton to carry.

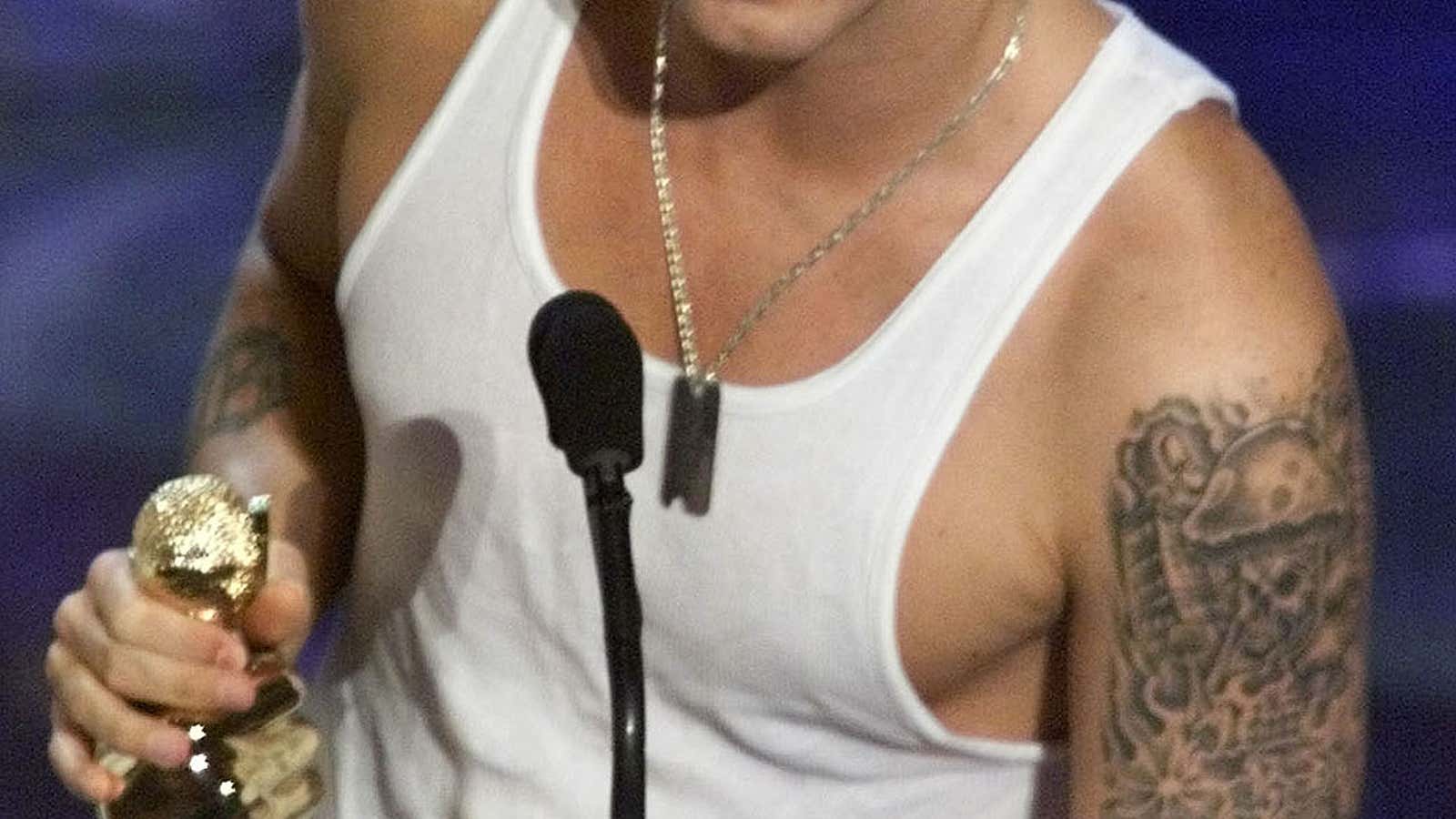

So what are we to call them? The shirts themselves are still a classic staple. White is good on everyone especially with a summer glow, they’re inexpensive, and on women they convey a slightly sexy, butchy quality that I find more alluring than a spaghetti strap. They’re the rare garment that does something nice for breasts of all sizes—and they’re not even designed for women.

Throughout the recent Times story the writer refers to them as “A-shirts” which is fashion jargony—like, “suiting” or “pant” in the singular. It sounds pretentious and it’s just not going to catch on. The Delia’s catalog, that arbiter of 90s white girl fashion, adorably fell on the right side of history, opting to call them “Grandpa tanks,” which is a perfectly suitable moniker. Happily, Queer Eye holds an even better answer.

In episode four of the first season the five hosts of the makeover show sit watching their first gay subject nervously choose an outfit for a party he is hosting, during which he plans on telling his step-mother that he is gay. “You can’t really come out in a wife lover,” says Jonathan Van Ness, with approval as their pupil switches a revealing white undershirt for a more polished polo.

Van Ness has changed modern slang more than any other individual in recent memory, with his signature uptalk and personal aura of positivity—and his take is exactly right for the moment. Wife lover provides the same sort of edginess that wife beater did, because it invites conversation, yet is an obvious correction. An inclusive, friendly, firm correction. Steeped in gender positivity and a sense of verbal reclamation, wife lover is at once wholly understandable and completely novel. It just makes sense—which is why I love it as much as the shirt itself.